How charities and advisors can work together for the benefit of all.

How charities and advisors can work together for the benefit of all.

During a recent presentation to a group of educational fund development executives, a representative of a leading university made the following observation: “Nonprofits are at war with the financial world, and we are losing!” This, understandably, sparked a vigorous discussion. While I certainly don’t agree that the for-profit and nonprofit gift planning sectors are engaged in a destructive conflict, the fact that such a statement was made in a public forum suggests we should revisit this issue.

The need for cooperation

Over the years, we at Sharpe Group have come to realize that the development professionals who are most successful at encouraging and implementing more complex charitable transactions (often referred to as “planned gifts”) are the ones who understand that these gifts can only be completed with the cooperation and coordination of many parties.

Since 1987, we’ve used the following definition of “planned giving” to describe the essence of the process:

“A planned gift is any gift of any kind or any amount given for any purpose—operations, capital expansion, or endowment—whether given currently or deferred, if the assistance of a professional staff person, qualified volunteer or the donor’s advisors is necessary to complete the gift. In addition, it may be any gift that is carefully considered by a donor in light of estate and financial plans.” *

Inherent in this definition is that teamwork is normally required to complete more complex charitable gifts. Few nonprofits or for-profit advisors are in a position to complete the process by themselves.

Let’s examine how the various parties involved in charitable gift planning can work together effectively to minimize friction and maximize benefits for all.

Two approaches

Two distinct approaches to the gift planning process have evolved over time, one emanating from charities over centuries, the other from for-profit planners who have taken a more active role in recent decades.

Does this mean that charities and the for-profit planning community are locked in a forced public embrace, while behind the scenes they engage in a competition for resources that may not be in anyone’s best interest? NO! So, what does the process behind a successful planned gift look like?

To compete or “complete”?

It’s easy to fall into the trap of believing that competition is inevitable—until one breaks down the process of completing a planned gift into distinct and interrelated components.

Let’s look at the acronym C-O-M-P-L-E-T-E to understand how the various parties can effectively work together to adequately fund the charitable dimension of U.S. society.

Communicate. The gift planning process begins with someone communicating to the donor/client the benefits of well-planned charitable gifts. Through increased channels of communication, the donor/client may learn of charitable gift planning opportunities from any number of both nonprofit and for-profit sources.

Open discussion. Discussions of planned gifts may be initiated in the course of ongoing fundraising activities undertaken by a charity where a donor expresses a desire to give, but is reluctant to proceed because of natural financial concerns. In other cases, the subject may arise in the context of overall estate and financial planning during discussions with a professional advisor.

Motivate the donor. For any gift to proceed from this point, the donor/client must be motivated to make what may be an irrevocable transfer of assets in exchange for income, tax savings and other benefits that are almost certain to have less economic value than the amount transferred to fund the gift. The reasons individuals make charitable gifts are many and varied, and the motivations for any two gifts may never be the same.

Propose a solution. After a motivated donor/client has learned about planned gifts and engages in discussion with a charity and/or an advisor, someone must propose a solution tailored to the donor’s needs. In most cases, the party who initiated the discussion with the donor/client will take the lead at this point.

Legal review. Many donors/clients will seek the counsel of their attorneys before completing a planned gift. Keep in mind that certain gift vehicles such as a will can only be legally drafted by an attorney.

Execute the plan. The next step in “completing” a gift is to actually execute the plan. When more sophisticated gift plans are involved, the services of a number of parties may be required. In almost no case other than a charitable gift annuity will a charity be able to fully execute a gift plan without the participation of one or more other advisors.

Trust or asset management. Where charitable trusts and certain other types of gifts are concerned, there must be an ongoing trustee or other manager or administrator of funds. This may or may not be a different entity from the parties involved in the early stages.

Evaluate the results. Finally, one or more individuals should be involved on an ongoing basis to ensure donor/client satisfaction. This will often, but not necessarily, be the same party who initially communicated and proposed the gift.

Achieving harmony

The best results are achieved when nonprofit and for-profit entities coordinate their roles in the gift process. Understanding, balancing and reconciling the interests of the various individuals involved is the key to successful planned gifts.

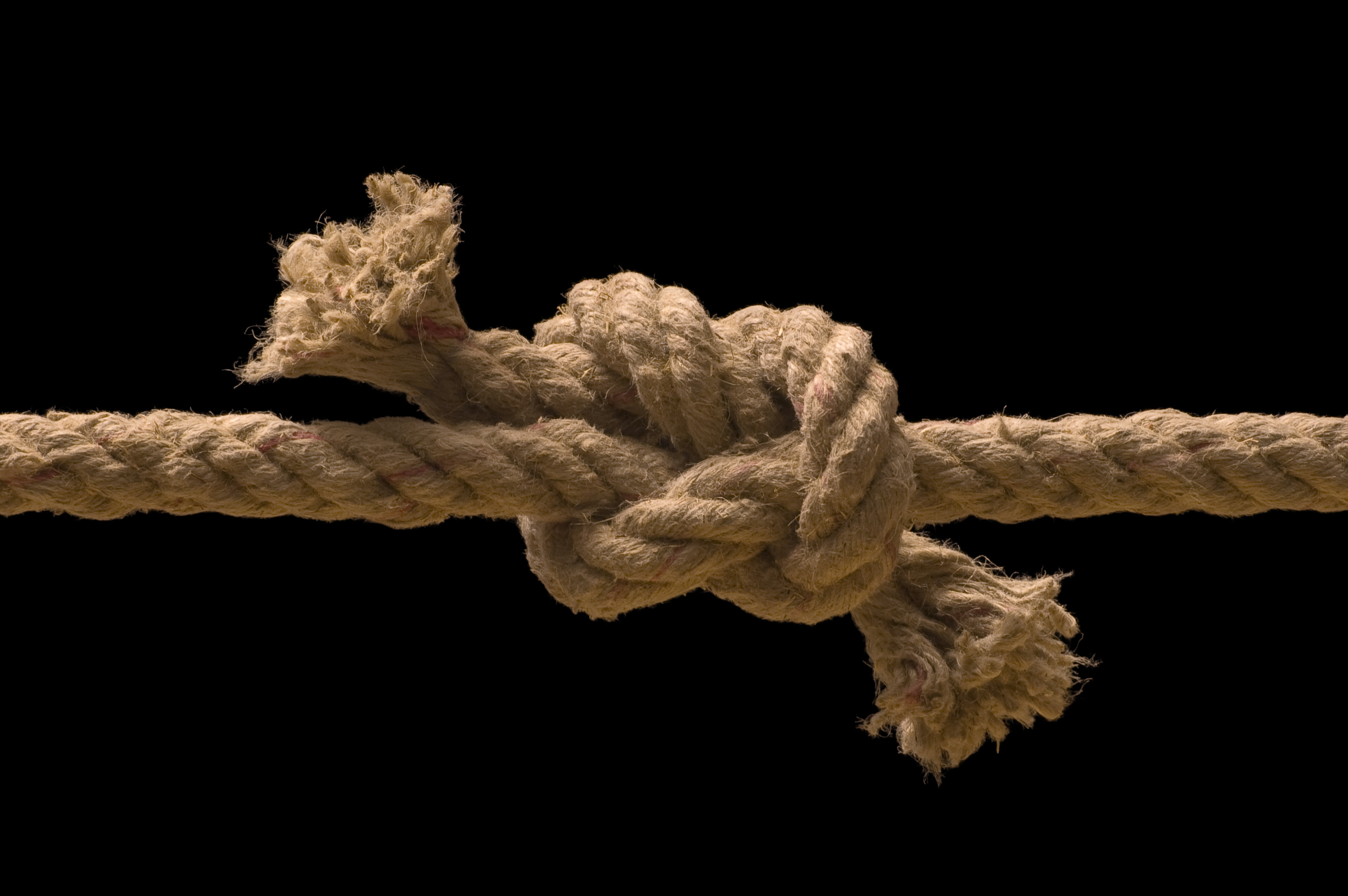

Attempts by either a nonprofit or one or more advisors to control the gift planning process will normally limit prospects for success. Instead of a linear process, it may be best to think of this procedure as a circular flow in which a gift’s impact can be maximized only through harmonious cooperation among all parties who may enter and/or exit at various points.

And keep in mind the process doesn’t always begin with communication by a charity or an advisor. Donors/clients may instead be self-motivated by life circumstances and deeply felt desires and initiate the planning process themselves.

So, in addition to working closely with advisors, it is important to know when to take the lead in suggesting a gift and when to help a donor realize their pre-existing goals. This will greatly increase the chance for a positive experience for all involved.

This article was excerpted from an article under the same title in the July 2017 issue of Trusts & Estates magazine. ■

* “An Integrated Concept for Financial Development,” Give & Take, Vol. 20, No. 4 (March 1988).

Robert F. Sharpe, Jr. is Chairman and Chief Consultant of Sharpe Group.