In last month’s issue of Give & Take we examined the underlying factors that motivate people to make charitable gifts: religion, social theory, political orientation, emotions, and economics and other factors. In reality, gifts are rarely motivated by just one of these concerns; they typically result from the complex interaction of several of these factors, changing with each donor and his or her particular circumstances.

But it is not enough simply to explore why donors make gifts. In today’s environment, it is becoming more and more important to examine why people sometimes don’t make gifts they would otherwise like to complete. Understanding the financial concerns that can stop people from making gifts is the key to making sense of what is commonly referred to as “planned giving” or “gift planning.”

Experience shows that the financial concerns that can act as “demotivators” of charitable gifts fall into four broad categories:

- Dying too soon

- Living too long

- Unexpected illness and other economic emergency

- Mental and physical disability.

Successful gift planners understand these fears and know how to use gift planning vehicles to create solutions.

Dying too soon

Many persons who would like to make a substantial gift worry that they could pass away without fulfilling their financial responsibilities to loved ones. It seems no one is immune from these anxieties, regardless of age. Younger persons may be anxious about providing for dependent children. Those in their middle years feel a responsibility to care for aging parents, and an older donor’s need to care for a surviving spouse often eclipses the desire to make charitable gifts.

Living too long

About the time that people begin to worry less about dying too soon, they can become anxious about outliving their resources, especially in times of lower interest rates and fluctuations in equity markets. Fundraisers enjoyed a reprieve from this problem during the past two decades, when rapid economic growth and relatively high interest rates made many donors feel a greater sense of financial invulnerability. Now, however, more and more persons are beginning to contemplate how they will support themselves over the long term in times of single digit returns on both equities and income-producing investments.

Illness and economic emergency

As the cost of healthcare continues to rise, the need to preserve funds for a potential illness is becoming increasingly pressing. Many also worry about the health of the economy and are wondering if their jobs are secure.

Mental and/or physical disability

As life expectancies increase, persons of all ages are beginning to realize the importance of preparing for the possibility of long-term mental or physical disability.

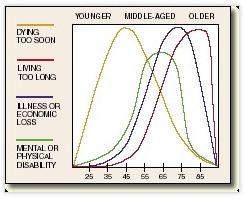

The mixture of one or more of the above concerns is at the heart of most persons’ decisions not to make a larger gift they would otherwise like to make. These fears do not remain constant throughout life but rather vary with age and economic capability, as seen in the chart above.

The role of gift planning

To raise significant funds in today’s environment, development officers must acknowledge the concerns outlined above and determine if and how a gift planning tool can help alleviate these anxieties and fulfill a donor’s desire to give. When the donor’s best interests are kept at the forefront, the process of gift planning can and does make perfect sense.

There are two basic categories of gift planning vehicles that can help a motivated, but anxious, donor make a gift. Many gift plans allow donors to make revocable gifts that give donors the freedom to change their minds if they need to access the funds at a later date. Because their revocability precludes tax benefits, these plans are also sometimes referred to as “non-qualified” plans. Development officers at times refer to these plans as “expectancies” because no gift is actually completed from a legal standpoint until someone’s death. The primary plans that fall into the revocable/non-qualified/expectancy category include the following:

• bequests via will and living trusts

• remainders of retirement plans

• life insurance beneficiary designations

• jointly owned investments with rights of survivorship.

On the other hand, irrevocable gifts involve a commitment to the permanent transfer of one or more interests in property. Because the donor has parted with something at the time of the gift, tax benefits are often available. These gifts are thus also sometimes referred to as “qualified” plans. And because the enjoyment of the gift is delayed to some later point in time, these gifts are often referred to as “deferred gifts.”

Irrevocable/qualified/deferred gifts are built on an underlying “operating platform” that is a trust, contract, or deed. These plans include the following:

• gift annuities

• charitable remainder trusts

• pooled income funds

• charitable lead trusts

• life estates in real estate.

The revocable and irrevocable plans described above are often referred to collectively as “planned gifts,” an umbrella term that actually includes both “expectancies” and “deferred gifts.”

Prescribing the right plan

The process of deciding which plan is best for the donor starts with listening to both the donor’s motivations and hesitations. If you have a prospective donor who clearly would make a gift but for one of these common fears, look below for some possible solutions.

Dying too soon

Bequests via will. The most common form of planned gift is the gift by will, with the largest bequests typically coming from the residue of an estate. Because this plan assures that a gift is made only at death and only after specifically providing for loved ones, bequest gifts appeal to persons who are afraid of depriving an heir of economic security. Leaving retirement plan proceeds or the remainder of a retirement plan or living trust to charity can accomplish the same result as a bequest with probate savings and possible other advantages.

Charitable lead trusts. Many planners place too much emphasis on the estate tax benefits a lead trust can offer. There are much more effective ways to pass property to family members. As a result, lead trusts are typically entered into by people who want to make significant charitable gifts over time but do not wish to disinherit their heirs or die without providing for their future economic security. The lead trust is one answer in this situation, as it allows persons to make the gift they wish to make while dealing with the fear they will “die too soon.” To such persons, the tax savings are important but not necessarily the primary motivator.

Living too long

Bequests via will, trusts, retirement plans, and life insurance. Like those worried about dying too soon, donors concerned about living too long will often delay a substantial gift until their death so they are assured access to all of their funds. The gift is usually “deferred” until death, but charitable remainder trusts for a term of years offer the option of keeping income for a limited period of time.

Gift annuities. Ironically, the fear of outliving funds can lead others to transfer funds irrevocably to charity in exchange for a lifetime of fixed payments. Deferred gift annuities offer a solution for someone who has adequate income now but worries about needing income in the future.

Charitable remainder trusts and pooled income funds. These plans offer many of the same advantages as bequests and gift annuities for those concerned with long-term economic security.

Life estate agreements. Transferring the ownership of a home at death while retaining the right to occupy and enjoy the home for life offers current tax benefits while helping maintain financial security.

Charitable lead trusts. A donor who does not need income today but wants to be able to access principal in the future may be interested in a variation of the charitable lead trust where the ownership of the funds reverts to the donor at the end of a period of time.

Illness and economic misfortune

Charitable bequests at death. As discussed above, bequests allow retention of funds if necessary in case of a temporary illness or economic reversal.

Gift annuities. Gift annuities assure a steady flow of income for medications and other illness-related expenses in later life.

Charitable remainder trusts. When a donor transfers assets to a charitable remainder trust, the transfer must be irrevocable, largely because of the tax savings involved. These trusts existed prior to tax savings, however. Why? One reason is that when you create such a trust the bad news is you cannot access your principal if needed. The good news is that no one else, including creditors, can either. For this reason, some persons who would not otherwise make a large charitable gift may do so in a way that assures that no matter what happens, they will always have the income from the trust.

Mental and/or physical disability

Gift annuities. Gift annuities provide an income source that will continue regardless of the donor’s mental or physical health. This is especially important for those who worry about being able to manage their assets in later life in case of permanent mental and/or physical disability.

Charitable remainder trusts. Charitable trusts offer more flexibility than gift annuities. They are often used by persons who would like to make large gifts but want to ensure that an income is retained in case of disability. Unlike a gift annuity, a charitable trust allows the donor to create a structure that can provide future increases in the amount of income received and to select the trustee of the funds.

Taxing issues

Any gift, revocable or irrevocable, in which funds are transferred at death can offer estate tax savings. But as over 90% of charitable bequests come from nontaxable estates, tax avoidance is obviously not the only motivation for such gifts.

Tax savings are more of a factor for irrevocable gifts that involve transfers of assets during lifetime with a retained interest for the donor or another person. The charitable benefits generally amount to what the donor gave minus what the donor retained, but far too much energy is expended in the process of determining these benefits, maximizing them, and then pretending they are the prime motivator for the gift. In fact, they are only one of many benefits of the gift and almost always total only a fraction of the assets transferred.

The motivation to make a gift clearly comes from somewhere else. The key for gift planners is to view the process of gift planning as a way to help donors overcome their fears and make the gift they feel inspired to make.

There are two ways to approach gift planning. You can begin with a “who”—a prospective donor—and then find a “why,” “what,” “when,” and “how” to finalize the gift. Or you can start with the solution and work backwards to the challenge facing the donor.

The first scenario occurs naturally when an experienced development officer is working directly with donors. When focusing on the “who” and “why” of the gift, the development officer will naturally be led to the “what,” “when,” and “how” and can often arrive at an agreeable situation for both parties.

But what about the majority of donors you never have an opportunity to talk with face to face? This is where the mass communications aspect of gift planning comes into play. Through targeting information based on the age and wealth of donors, information can be conveyed that is designed to anticipate the reasons people may not make larger gifts. Various gift planning concepts can be exposed along with examples of persons who have made use of them. Donors are then given an opportunity to self-identify themselves as having an interest in making a gift in a particular way.

At that point, a potential donor has provided you with the what, when, and how of the gift. It is tempting to try to complete a gift at that point, but unless you discover who the donor is, and why the donor wants to give, you may proceed with a gift that is not the best fit for that donor.

Being a successful gift planner always requires patience and a genuine concern for donors’ well-being. As long as you keep their wishes and needs at the forefront, you can use your experience and expertise to help them make what may be their gift of a lifetime.

Editor’s note: This article completes a two-part series begun in the February 2003 issue with “Why Do People Give?” Both articles are based on material covered in more depth in the Sharpe seminar series. This article is excerpted from Session 3 of Major Gift Planning I. See page 7 for information about future seminar offerings.