Amy Shehee is Director of Gift Planning at Berea College in Kentucky. In an age of skyrocketing tuition prices at many colleges and universities, Berea College distinguishes itself by awarding full tuition scholarships to every student. Here Ms. Shehee shares the story of Berea College’s extraordinary mission.

Amy Shehee is Director of Gift Planning at Berea College in Kentucky. In an age of skyrocketing tuition prices at many colleges and universities, Berea College distinguishes itself by awarding full tuition scholarships to every student. Here Ms. Shehee shares the story of Berea College’s extraordinary mission.

Give & Take: Can you share some of Berea’s history?

Shehee: Berea College was founded in 1855 by ardent abolitionists and radical reformers who had a vision of a school that would provide an education for all students regardless of race or gender. When Berea College was formally opened, it was the first interracial and coeducational institution of higher learning in the South.

Today, Berea continues to present a unique educational model. Every student who is admitted to Berea receives a full tuition scholarship for four years. However, to gain admission, a student must demonstrate financial need as determined by the Free Application for Federal Student Aid (FAFSA). As a result, over 90 percent of our students are Pell grant eligible.

In fact, an applicant to Berea could have top grades and test scores, yet be denied admission if the student’s family makes more than the allowable amount (roughly $50,000 for a family of four with one student in college).

This dedication to helping underprivileged students is one of the Eight Great Commitments that define Berea’s mission. Another is to serve the Appalachian region, where Berea is situated. Roughly 80 percent of our students come from Kentucky or other areas of southern Appalachia. Another 10 percent reside in the rest of the United States, and the remainder are international students who come to Berea from struggling, often war-torn nations. Many of them return to their home countries after graduation and become leaders in effecting social and economic change.

Give & Take: How does Berea fund approximately 1,600 full-tuition scholarships every year?

Give & Take: How does Berea fund approximately 1,600 full-tuition scholarships every year?

Shehee: Since the 1920s, Berea’s Board of Trustees has directed that all unrestricted bequests be placed into the endowment. After 94 years of adhering to this practice, our endowment today is over $1 billion.

While that seems like an extraordinary amount, especially for a small liberal arts college, the income from that endowment has to cover a wide range of expenses, from professors’ salaries to the utility bill. Roughly 80 to 85 percent of our annual income at Berea comes from the spendable income generated by our endowment. The rest is acquired through a combination of federal grants and annual fundraising.

Give & Take: What percentage of your yearly fundraising total comes in the form of bequests?

Shehee: Until recently, bequests were responsible for 40 to 60 percent of our annual contributions. That number is far above the 10 to 15 percent average seen at many nonprofits. In the last few years, however, we started experiencing a sharp and unexpected decline in our bequest income. Because bequests feed into our endowment, which in turn provides the funds for our tuition replacement program, the decline was of great concern to all of us on campus. We asked Robert Sharpe and Sharpe Group to help us find out what was going wrong.

Robert and others on the Sharpe team utilized several of their program assessment tools in their analysis of our fundraising program, both past and present, and discovered the source of the problem. We started our donor acquisition program 40 years ago, in 1974, and for many years made it a priority in our fundraising efforts. Unfortunately, in recent years we either cut or failed to increase funding for these efforts. As a consequence, we started acquiring fewer donors, which in turn affected the number of bequests we received each year. Robert was able to explain the problem and outline a clear solution.

Give & Take: How would you characterize Berea’s donors?

Shehee: The majority of donors to most colleges are alumni or parents of current or former students. Berea’s donor base more closely resembles that of a national charity. Only about 20 percent of our donors are alumni. The other 80 percent heard about Berea’s mission in other ways: from living in the region, from hearing stories about Berea in the media or by knowing someone whose life was changed for the better by attending Berea. Our donors support Berea not necessarily because of their experiences at the college but because they see it as a model for an alternative type of higher education.

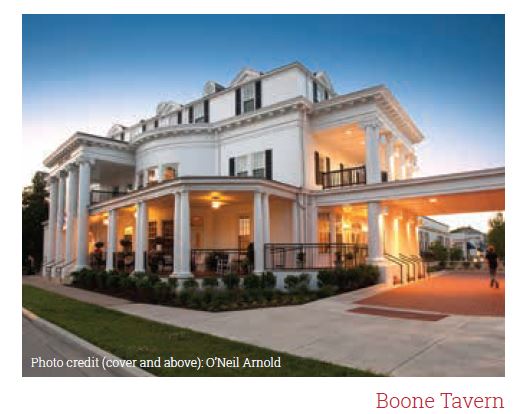

Donors also sometimes discover Berea through our gateway partners, which often employ Berea students. Berea is one of only seven official labor colleges in the United States. Every student who attends Berea is required to work at least 10 hours per week in return for a small salary. After freshman year, students choose their positions, and work opportunities include everything from the college farm to the office of finance to the craft program. Many donors become interested in Berea after purchasing some of the crafts made by students in the student craft program. Others first learn about Berea by interacting with students working in Berea’s historic inn, Boone Tavern.

For instance, one of our African-American donors told us a story that outlines the special qualities of Berea. When traveling with his wife from the North to the South 50 years ago, in the days of segregation, they became worried that they may not be able to find a restaurant or hotel in the South that would serve them. They decided to take a chance on Boone Tavern, and the students and staff there welcomed them with open arms. They spent the night and left in the morning agreeing that if they ever had a million dollars, they would give it to Berea. He and his wife have supported Berea ever since.

Give & Take: Do you have a donor recognition society to help steward relationships with special donors?

Shehee: Yes. In every publication we send out, whether it is specifically about planned giving or not, we insert information about gift annuities and also include an opportunity for donors to indicate if they have included Berea in their estate plans. Every year, a number of donors establish a gift annuity with us as a result, while others share they have already established an estate gift benefitting Berea. In those cases, we typically send a gift officer to visit that individual and see if there’s a possibility of an outright gift as well.

When donors notify us of an estate gift in advance, they are invited to join the Great Commitments Society. Members receive a welcome kit and are invited to campus once a year for a presidential reception. We stay in touch throughout the year with birthday cards, our planned giving newsletter and donor visits.

Give & Take: How did you become involved in gift planning?

Shehee: I am a Berea alumna. I never imagined when I graduated or while attending law school that I would end up being a fundraiser, but Berea’s compelling mission and its transformative impact on students called me back here. People who give to Berea tend to really have a passion about the college. Being able to work with them is a blessing every day.

Give & Take: Do you have any advice you’d like to pass on to people who are new to the field of gift planning?

Shehee: The most important thing is to have a donor-centered outlook. Meet your donors where they are.

If your prospective donors already believe in your mission, your next step is to find out what their needs and circumstances are and make fulfilling their goals your main priority. Fundraisers sometimes make the mistake of trying to push an institutional agenda on donors. That’s a short-term strategy at best. If you’re good at sales, you can probably convince a donor to make an outright gift. But if that’s not where the donor’s passion is, that one gift may be the last.

By keeping the donor’s needs a top priority, I have even talked some donors out of making a gift that doesn’t make sense for them. I advise people to proceed with caution with certain planned gifts if their circumstances don’t warrant it. And I always tell people to speak with their financial advisor. In those times when I’ve told donors that a certain planned gift is not the best route for them, I may lose the gift but I gain their trust. Their trust is far more important.