By: Robert F. Sharpe, Jr.

A recent report suggests a tremendous increase in major donors who are under the age of 40, but a closer look reveals a different story.

Those who follow the philanthropic press should be aware of the rebound in giving by the wealthiest Americans, as reflected in The Chronicle of Philanthropy’s recent summary of the top 50 donors in the U.S. in 2014. While headlines have touted a tremendous growth in giving by younger donors, a closer examination of the underlying data reveals a slightly different story―one that may be helpful for those charged with encouraging larger gifts now and in coming years.

Those who follow the philanthropic press should be aware of the rebound in giving by the wealthiest Americans, as reflected in The Chronicle of Philanthropy’s recent summary of the top 50 donors in the U.S. in 2014. While headlines have touted a tremendous growth in giving by younger donors, a closer examination of the underlying data reveals a slightly different story―one that may be helpful for those charged with encouraging larger gifts now and in coming years.

Looking beneath the surface.

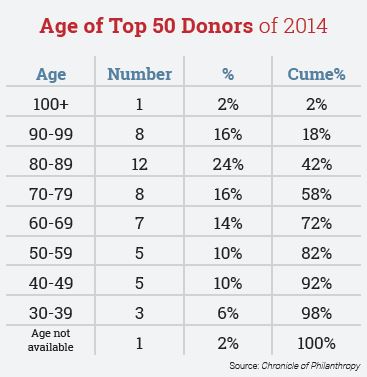

Let’s examine the Chronicle’s list of the top 50 donors in 2014. Note that over 40 percent were at least 80 years old, roughly 60 percent were at least 70 and over 70 percent were 60 and older (see chart left).

Despite the widespread reports of a tremendous increase in the number of tech entrepreneurs under 40 joining the ranks of the top 50 donors, only three individuals met that criteria. Further, the data reveals that only eight (16 percent) of these donors were under the age of 50.

A Sharpe Group client that works in environmental protection, a cause that is thought by many to attract primarily younger donors, appended ages to its file. They found that 72 percent of its donors of $500 or more were over age 65 and 32 percent were over age 80 (see second chart- below on right).

KThese findings are typical among Sharpe clients that engage in a broad range of other philanthropic activity including education, healthcare, religion, social services and the arts. As noted in the April issue of Give & Take, America’s nonprofits are still heavily reliant on the remaining members of the G.I. Generation and the Silent Generation that followed them. According to The Chronicle of Philanthropy study referenced previously, baby boomers are as yet accounting for just 24 percent of the top donors and the Generation X and millennials just 16 percent, which is to be expected given the fact that most are still in the stage of life where they are accumulating rather than distributing assets.

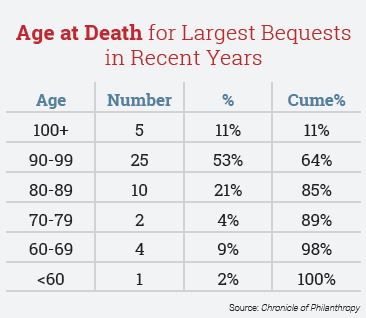

When looking at Chronicle reports of the top bequests received since 2009, the generational pattern is even more pronounced (see chart on left).

When looking at Chronicle reports of the top bequests received since 2009, the generational pattern is even more pronounced (see chart on left).

Note that only five of the largest bequests (11 percent) came from individuals who passed away under age 70. Nearly two-thirds died over the age of 90, and 85 percent over the age of 80. This age distribution for large bequests very closely mirrors figures from the IRS and other reports on the age of those who leave charitable bequests.

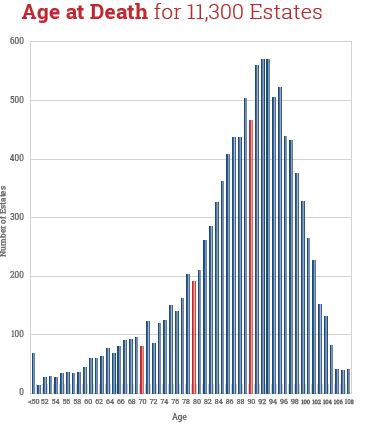

For over 30 years Sharpe Group has tracked the age at death for bequest donors to a large number of nonprofits. The most recent summary of age at death of over 11,000 bequests of all sizes received by more than 100 representative organizations over the past few years reveals that just 11 percent of bequest donors passed way under age 70. In other words, 89 percent of bequest donors died at age 70 or older. This is exactly the same as the age distribution at death of those who left the largest bequests as reported by The Chronicle. The average age at death in this group of bequest donors was 85 and the most common age at death was 90 (see chart below).

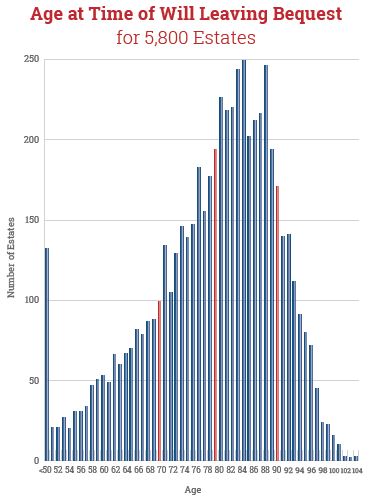

But perhaps these people made the wills that left their bequests much earlier in life? Not so. Of the nearly 6,000 wills in which the date of the will’s execution was available, 80 percent of decedents who included a charitable bequest executed the will at age 70 or older, with some 50 percent doing so at age 80 or older (see chart on right).

But perhaps these people made the wills that left their bequests much earlier in life? Not so. Of the nearly 6,000 wills in which the date of the will’s execution was available, 80 percent of decedents who included a charitable bequest executed the will at age 70 or older, with some 50 percent doing so at age 80 or older (see chart on right).

This information confirms recent findings by Dr. Russell James based on the results of a long-term research project being conducted by the University of Michigan (See Give & Take, February, 2015) that 80 percent of charitable bequest dollars are coming from persons who made the relevant will at age 80 and older. Further, he found that among over 10,000 survey respondents who passed away during the research project, two-thirds of all charitable estates and over half of all charitable estate dollars came from those who reported having no charitable gifts included in their plans within five years of death.

What does all this mean?

The primary takeaway is that whether you want to encourage major outright or deferred gifts in today’s environment, it is important to reach out to all age ranges within your constituency, but it is especially vital to devote a significant amount of your time and budget to persons over the age of 70. With all the attention now being given to the concentration of wealth in the top 1 percent of Americans, we must also realize that those in this 1 percent are much older on average than the general population. We might want to term this vital group of donors as the emerging

The primary takeaway is that whether you want to encourage major outright or deferred gifts in today’s environment, it is important to reach out to all age ranges within your constituency, but it is especially vital to devote a significant amount of your time and budget to persons over the age of 70. With all the attention now being given to the concentration of wealth in the top 1 percent of Americans, we must also realize that those in this 1 percent are much older on average than the general population. We might want to term this vital group of donors as the emerging

“philanthrogerontroplutocracy.”

Perhaps the most exciting aspect of this reality is that the oldest of 76 million living baby boomers will reach the age of 70 next year. Might this mean the long-predicted “golden age” of major giving by baby boomers is finally just around the corner?

For those who want to influence bequest income received over the next ten years, however, it is increasingly prudent to direct appropriate attention to donors currently over the age of 75. While the baby boomers’ bequests may “boom” in the future, all of them are currently under the age of 70, meaning for at least the next decade the majority of bequests received will continue to come from the remainder of the G.I. Generation and the bulk of the Silent Generation who have still not made their final estate plans.

For those who want to influence bequest income received over the next ten years, however, it is increasingly prudent to direct appropriate attention to donors currently over the age of 75. While the baby boomers’ bequests may “boom” in the future, all of them are currently under the age of 70, meaning for at least the next decade the majority of bequests received will continue to come from the remainder of the G.I. Generation and the bulk of the Silent Generation who have still not made their final estate plans.

In fact, many donors now over the age of 70 have yet to make their largest outright gift, much less plan their bequests. In the wake of these realities, act carefully to ensure you aren’t responsible for a baby boom bequest “bust” over the next decade.

While this course of action may seem obvious, in practice it may present challenges. Many donors in the 70-and-older age range are now entering, or are well into, their retirement years. Many are living on income derived from a lifetime of accumulated investments and may be “asset rich” and “income poor.”

Beyond bequests.

It may be tempting to “default” to a simple bequest or other estate commitment, because these gifts are seen by many as “simple” and for the most part don’t require specialized knowledge of the gift planner.

While the majority of gifts may, in fact, come through wills and other gifts that are not completed until a donor’s passing, don’t overlook gifts that can provide more certainty for the charitable recipient and the possibility of near-term spendable cash flow prior to the donor’s passing. Examples include termination of gift annuities and other life income gifts prior to death, charitable remainder trusts designed to split payments between donors and charitable purposes, life income gifts for older loved ones and charitable lead trusts that result in current gift income before providing an inheritance for other heirs.

It may also be possible to encourage outright gifts from donors who shied away from such gifts when they were younger, and instead opted for a bequest commitment. Often, when donors reach their later years, they realize they can actually afford to make outright major current gifts that may have seemed impossible at an earlier time. Accelerating bequest gifts from older donors may be a welcome and unexpected source of gift income over the next decade while we await the initial wave of estate gifts from baby boomers.

The key to success now, as always, is to take a balanced approach and not be distracted by the fads of the day that are in some cases born of wishful thinking. Yes, younger donors are important and now is the time to begin acquiring and educating them, but this should not be done at the expense of harvesting the gifts of a lifetime from those who have been an important part of the past and can be expected to provide the bulk of philanthropic funding for the foreseeable future. ■