Which would you prefer to receive as a charitable gift—an outright gift of $100,000 or a $1,000,000 life income gift?

At first glance, the life income gift may appear to be the most valuable and attractive simply because it has the most zeroes and commas. In reality, a number of factors can affect the relative value of a gift and each must be carefully considered. For example, certain types of restrictions, the time value of money, costs associated with the gift, the form of the gift, etc., can all impact the actual value of a particular gift.

Still, judging by their programs, many development professionals seem to believe that all planned gifts are valuable by their very nature. However, just because a gift is arranged through a planned giving vehicle such as a charitable remainder trust or gift annuity does not mean that it is more valuable than a simple current, outright gift via a check or publicly traded securities.

Case in point

I recall the story of one young development officer in particular. This development officer had a major donor who responded to a life income gift marketing initiative. Needless to say the development officer was excited by the prospect of completing a life income plan with this donor.

Perhaps due to this excitement, the development officer was unable to see that this donor was equally capable of making an outright gift or completing some type of deferred gift arrangement. The donor was simply seeking the development officer’s advice as to how his gift could best be completed.

In this case the donor was in the highest income tax bracket and had recently realized large gains from various business transactions. As a result, the donor was more interested in maximizing his tax deductions today than in producing future income. For these reasons and others the donor eventually completed an outright gift that was immediately put to use by the charitable recipient rather than funding a deferred gift with reduced tax benefits that produced additional income the donor did not need.

Making fair comparisons

Let’s return to our hypothetical question concerning an outright gift of $100,000 or a $1 million life income gift. Which one is more valuable? The answer, of course, depends on many factors. For example, what is the age or ages of the donor and/or income recipient? What is the payout rate of the life income gift? What is the “discount rate,” or opportunity cost, while an institution waits for funds to be received?

For example, suppose a 50-year-old couple were to establish a $1 million charitable remainder unitrust with a 5% payout and the trust were funded with $1 million in highly appreciated securities. The charitable remainder judging from the income tax deduction would be $191,800 and actuarial tables indicate that no funds will be available for charitable use for some 40 years. Wouldn’t a charitable recipient be better off with a pledge of $50,000 per year for five years? The donors would enjoy 25% more in tax deductions ($250,000 versus $191,800) and if they used stock to fund their gifts they would completely avoid capital gains tax and still own stock worth over $1 million at the end of the five-year pledge period (assuming traditional market growth).

Another alternative would be to fund the charitable remainder trust, give the first five year’s payments to charity, also resulting in a $250,000 gift, while the donors enjoy income for the remainder of their lives. The charity would eventually receive the remainder. The latter alternative is one that combines a current and deferred gift and maximizes the total value for the charity.

Value relative to time

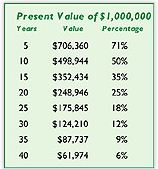

A vital concept to understanding the relative value of various planned gifts is present value analysis. Basically, this amounts to solving for how much it would take today to buy a dollar at some future point in time. Present value analysis depends upon earnings and discount rate assumptions. Note the chart at right that shows the present value of $1 million assuming a 7.2% discount rate for various time periods.

At the 7.2% discount rate (the rate currently assumed for the purpose of calculating charitable deductions), a sum of money loses approximately 30% of its value every five years.

Making gifts count

Under accounting standards rules (FASB 116 and FASB 117) and many campaign reporting guidelines, deferred gifts must now be counted for financial purposes at their present value. This is another reason why it is important to recognize that all planned gifts are not equally valuable and it is critical to minimize the time period an institution must wait for the gift whenever possible.

Value to the donor counts, too

No matter how large or valuable a gift seems to be, no gift is valuable if the donor is not comfortable with it. In the final analysis, the only truly valuable gifts are ones that the donors are satisfied with and happy to give.

In many cases, planned giving vehicles provide donors with a unique way to meet a variety of personal and philanthropic goals in an efficient manner. The gift planner’s objective is to help the donor identify those goals and then consider which gift options best fit their particular needs. In some cases that may result in gifts of great value. In other cases the donor’s personal needs may be so great that the charitable gift portion of the transaction may be diminished. A proper perspective and balancing of interests is an essential part of the philanthropic process.