In the last few years there have been a number of reports in the press about significant bequests from the estates of widows—most notably the $1.5 billion bequest from the estate of Joan Kroc, widow of Ray Kroc, the founder of McDonald’s, and the multi-billion-dollar bequest from Leona Helmsley, widow of real estate magnate Harry Helmsley. Are such significant gifts from widows just isolated events, or do they represent a trend that should be noted by those who are responsible for encouraging funding to America’s nonprofits?

We believe that voluntarily funded entities will increasingly benefit from gifts from widows’ estates and that these bequests will represent a major part of the funding of many organizations and institutions in coming years.

Following the money

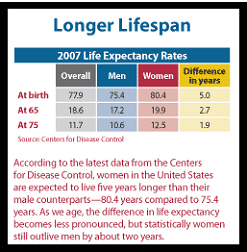

Women make up more than half of the American population and far more than half of the donor population of most charitable entities. And given women’s longer life spans, the older the donor base, the higher the percentage of women.

It has been reported that women control 80 percent or more of household spending and own over 60 percent of the assets in America. As men of the GI and Silent generations continue to pass away in larger numbers, we can expect even more assets to be controlled by older women. Persons of average means tend to leave all of their assets to a surviving spouse out of necessity, while the wealthy are encouraged to do so by the unlimited estate tax marital deduction. The ultimate disposition of a married couple’s property is thus determined in most cases by the surviving spouse (typically the wife) at her death.

It should not be surprising, therefore, that 70 percent or more of bequests to nonprofits typically come from the estates of women. Women are also responsible for the vast majority of charitable gift annuities and many other types of planned gift arrangements.

Age differences matter

When working with widows and other women, it is important to recognize that there may be major differences in giving behavior based on age. Women over 75 are less likely to have participated in the work force than younger women. They may have less experience in financial matters than younger women, although in the majority of cases they will find themselves completely responsible for the management of their finances in their later years. Women who came of age in the 1950s and later, however, are much more likely to have attended college and participated in the work force and are little different from their male counterparts when it comes to financial matters.

Working with widows

For those responsible for major and planned gift development, the ability to work effectively with older women, particularly widows, may be critical to fundraising success in coming years. Organizations now embarking on capital campaigns are finding that in many cases the married couples they relied on in past campaigns now consist solely of a surviving widow who is newly responsible for making charitable giving and other financial decisions.

To be successful in these and other fundraising efforts with widows, gift planners should keep a number of points in mind:

- It is vitally important that the mourning period be respected. Advisors and experienced fundraisers report that it can be two years or more before a widow feels comfortable considering larger gifts. It can take this long for the estate settlement process to be completed and for her to be familiar and comfortable with her new financial picture. Prematurely approaching a widow for a significant gift commitment can be unpleasant for all concerned and can cause permanent damage to the relationship.

- When the time is right to approach a widow for a gift, be prepared to gauge the nature and level of her donative intent. In some cases she will make a gift only out of what she perceives as an obligation to continue her husband’s support and has little or no personal interest or commitment to a cause, even though she continues to support it. In other cases, the spouses shared the interest in a charity and a close relationship can be expected to continue.

- Consider the particular impact of prevailing economic conditions on widows. Older persons who are living on accumulated assets tend to invest conservatively and thus live primarily on interest and dividends. In recent years their incomes may have been squeezed, and gifts may not be as large as those made in the past. Be careful when asking widows to increase the size of gifts as part of strategies designed to upgrade donors.

- Because of the way assets may be invested, widows may be especially interested in gift annuities and other gifts that provide them with a higher, fixed income. As fewer widows can be expected to be subject to estate tax now and in the future, they may also be interested in replacing a bequest with a life income gift that results in current tax benefits and a secure source of increased income.

- Especially in the case of wealthier widows, development executives should be prepared to work with one or more advisors who will often be consulted before making a larger charitable gift—whether current or deferred. These persons will often be longtime family advisors in whom the widow places a great deal of trust. Such advisors can sometimes have what practically amounts to veto power over the gifts contemplated by widows. In some cases, the most trusted advisor will be a child or other younger friend or relative.

- When working with wealthy widows and their advisors, it can be possible to arrange for very meaningful gifts to be made as part of their financial and estate planning. Keep in mind that the unlimited marital deduction referred to above results in deferring estate taxes to the estate of the second spouse to die. In the case of Ray and Joan Kroc, for example, the ultimate disposition of their property took place at the death of the surviving spouse.

Practical steps

Virtually every development program should thoughtfully consider how to maintain an appropriate relationship with the widows in its constituency. In many cases it may be advisable to appoint a staff person to assess the efforts directed toward fundraising from widows.

Care should be taken to make sure that widows are treated appropriately in direct mail efforts, events, major and planned gifts, and campaign activities. One idea that can immediately improve relations with widows is to acknowledge donors based on longevity of giving and cumulative giving as well as the amount recently donated. In some cases widows might be given life membership in higher level recognition societies based on their long history of support. This can help ensure that she doesn’t feel relegated to a lower recognition status as a result of the death of her husband.

When communicating on the subject of planned gifts, keep in mind that the vast majority of bequests and other planned gifts will come from older women, many of whom are widowed, divorced or have never married. For many organizations, focusing planned giving materials on women should be a habit and not an occasional effort. Most examples should be based on women, and the majority of donor testimonials should feature women. Examples and testimonials featuring male donors should in many cases be the exception to the rule.

Don’t forget memorial gift efforts. Some of the largest bequests are given to honor the memory of a deceased spouse. Where possible, include space on reply devices enclosed with current gift appeals that allow a person to designate a gift in memory or in honor of someone.

In the same vein, if a surviving spouse designates your organization to receive gifts in lieu of flowers to honor a deceased spouse or other loved one, make sure that all gifts are carefully tracked and the surviving spouse is given a list of the donors after an appropriate time has passed. Delivery of such a list in person can be the beginning of a new relationship with the widow or widower and can ultimately lead to a bequest or other planned gift in memory of a loved one.

These are just a few points to keep in mind when working with widows. Many of these suggestions could apply to widowers as well. The primary difference when working with widowers is that there are far fewer of them, and they tend to have a shorter life expectancy. In any event, now may be a good time to reflect on how well your programs are relating to widows and widowers as they will increasingly represent a major source of income for America’s nonprofit community.