On January 1, 2006, ongoing changes in federal estate tax laws will usher in a new era in charitable gift planning. Whether donors are considering a gift in the form of a bequest through a will, the remainder of a retirement plan, a gift of life insurance proceeds, or other means, estate tax considerations will play less of a role in motivating donors to make gifts that are completed through their estates at death.

That’s because the amount that individuals can leave through their estates free of federal estate tax will rise to $2 million on January 1. This will result in the elimination of estate tax for over 99% of Americans. In fact, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO)1 has estimated that just 16,700 decedents will be subject to estate tax in 2005. If 22% of those persons leave bequests to charity (the average based on 2004 IRS figures), the number of those affected by the estate tax who leave funds to charity will shrink to just under 3,700. Surveys have found that 8% or more of Americans plan to leave funds to charity. If that is the case, then there are upwards of 200,000 charitable estates each year, with less than 2% of them subject to taxes in 2005.

While it will be some time before we know the full impact of the elimination of the estate tax on charitable bequests, organizations and institutions that have long encouraged donors to leave funds to charity to avoid estate tax may have to rethink their approach. Complex plans driven by state-of-the-art software that rely on charitable gifts to eliminate estate taxes will simply be irrelevant to the vast majority of donors. While it is true that a small number of donors are still concerned about estate taxes, they are among the very wealthiest individuals, are typically well advised when it comes to these matters, and do not normally look to their charitable interests for guidance in estate planning.

The death of planned giving?

Does this mean the end of planned giving? Of course not. In fact, approached in the right vein, we believe the elimination of estate taxes can represent a tremendous opportunity to encourage charitably inclined persons to make larger bequests for charitable purposes than they might have previously considered.

Experienced development executives know that a large percentage of charitable bequests have tradition-ally come from older, childless persons, often widowed or never married. These persons typically leave relatively small amounts to nieces, nephews, siblings, or other friends and relatives, with the bulk of their estates left as residuary bequests to charitable interests—often four, five, six or more in number. The typical amount left to charity in the form of residuary estate gifts has been in the range of $150,000, with each of a number of charities receiving an average of $35,000 to $50,000. The vast majority of these estates have long fallen below the taxable threshold. These bequest donors typically gave smaller amounts during lifetime from incomes that were as modest as the value of their estates. In the case of these donors, their heirs would receive their entire estate were it not for charitable dispositions. The cost of the charitable bequests to the heirs is thus 100% of the dollars given in this way.

A larger universe?

Ironically, the elimination of the estate tax may expand the group of persons who make charitable gifts through their estate to include more wealthy persons with children. Consider that persons of wealth who wish to leave assets to their children must now pay estate taxes on many billions of dollars per year for the privilege of doing so. Elimination of the estate tax will put those tax dollars “in play.” The CBO has estimated that an immediate elimination of the estate tax would reduce estate tax revenues by $150 billion between 2006 and 2010, an average of $30 billion per year. Given these figures, there could be an extra $30 billion available each year for persons planning their estates to devote to any number of other uses.

Those who no longer owe estate taxes will have a choice to make. Should they allow their families to enjoy the entire windfall brought about by the elimination of estate taxes, or should they split it between their families and their charitable interests? The decision they make may to some extent depend on how the nation’s nonprofit community addresses the issue. Those who believe that wealthy persons will not leave funds to charity without an estate tax incentive may choose to lobby for the continuation of the estate tax so that charities will not be hurt. However, few boards can be expected to endorse that position given the fact that many trustees are themselves persons of significant wealth!

A better approach may be to inform wealthy donors of the increased control they may enjoy over their assets so they may carefully consider how to distribute those assets wisely. Keep in mind that many donors now decide how much they wish their loved ones to receive, pay the tax on that amount, and then leave what remains to charitable interests. As a result, charities may begin to receive all or a portion of the share formerly allotted to the government.

Lower tax can mean larger gifts

For those who now have taxable estates and must split assets between charitable recipients, taxes, and their families, elimination of estate taxes can actually mean they can leave more to their families and their charitable interests.

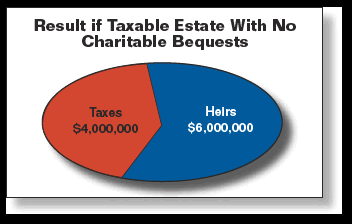

Let’s consider the case of a wealthy individual with a $10 million estate who would like to leave it all to her children. Here is the way her assets would be split at death under current law (taxes are approximate):

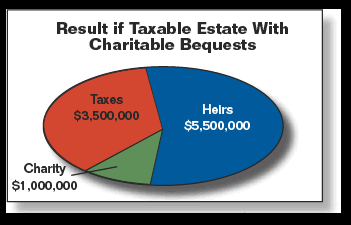

Suppose, like many others, she decided to leave bequests (in this case 10% of her estate) to charity.

Here is how the distribution would break out under current estate tax law:

Note that the family would receive $5.5 million and the “cost” of the charitable bequest to them would be $500,000.

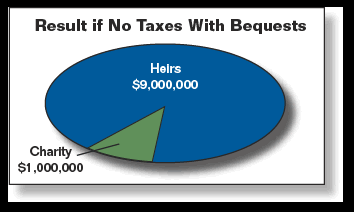

Now suppose the estate tax is repealed:

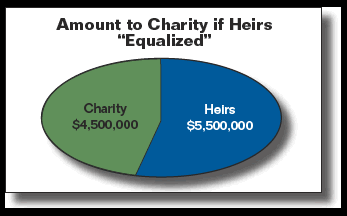

In this case, the heirs would receive $9 million, which is $3.5 million more than they would enjoy under the current tax regime, while the charity would still receive $1 million. Under these circumstances, the donor may choose to increase her charitable bequests to as much as $4.5 million, leaving $5.5 million for the children—the same amount they would receive if her estate were taxable.

The elimination of the estate tax would give this donor greater flexibility and more choices. She can increase her charitable bequest by any amount between $1 million and $4.5 million without depriving her children of the inheritance they would have received under current law when she decided to leave the $1 million to charity despite the cost to the children. Cases like this reveal that elimination of the estate tax would not necessarily lead to fewer funds for charity but might, in fact, result in greater amounts left to charity.

Individuals with inherited wealth may also begin to give more to charity. It is not uncommon for those who have inherited assets to feel that they were entrusted with the funds for the benefit of their family and thus do not have the right to give away “family money” at their death. With no estate tax, these persons may reconsider that position and leave all or a portion of what would have been expended in tax dollars for purposes that the family can agree will further commonly held objectives.

The desire to give remains

Given these circumstances, why would anyone argue that repeal of the estate tax would result in less to charity? Some may mistakenly argue that bequests under current law do not “cost” heirs anything as they simply take funds that would have been directed to pay estate taxes and given them to charity instead. However, making a charitable bequest has always had a cost, with or without an estate tax. Persons who accumulate $10 million normally know that their heirs receive less if they leave a bequest to charity. This at least partially explains why 80% or more of taxable estates have traditionally not included charitable dispositions even though 70% or more Americans contribute to charity during their lifetimes.

Every time a donor with children or other dependents makes a gift during his lifetime, he is deciding to deprive himself—and by extension his family—of the amount he would have had available to spend if he had kept the money and paid tax on it. Americans choose to deprive themselves and their families of close to $200 billion each year in this way. Should it be any surprise, then, that they choose to leave close to $20 billion per year to charity through their estates?

Would Americans stop making current gifts if there were no income tax? There is ample evidence that Americans supported non-profit endeavors well before the arrival of the income tax in 1913 and the estate tax in 1917. The bequests that provided initial funding for Harvard University, Johns Hopkins University, and the Smithsonian Institution in the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries are just three of many possible examples.

Scholarly studies have revealed that many among the ranks of the wealthy have indicated that they will, in fact, leave more to charity if the estate tax is eliminated. See “The Mind of the Millionaire: Findings from a National Survey on Wealth with Responsibility” by Paul Schervisch and John Havens, available at http://www.bc.edu/research/swri/meta-elements/pdf/mompub1.pdf. 2

Communication is key

Elimination of the estate tax presents a wonder-ful opportunity for nonprofits to dispel common misconceptions. For example, donors have been told for so long and so often about the estate tax savings of charitable gifts that they may believe the reason to give is vanishing with the estate tax.

Charities need to act now to tell donors that the elimination of the estate tax gives them new freedom and responsibility when it comes to the distribution of their assets. In addition, charities must make the case why their particular cause should receive a portion of the donor’s newfound wealth.

Emphasize other ways to give

The elimination of the estate tax will also bring into sharper focus the importance of making planned gifts during lifetime. Such gifts can serve to maximize the remaining tax and financial benefits and make it easier for motivated donors to give larger amounts. The income tax will not soon be eliminated, and the current plan to eliminate estate tax in 2010 leaves the gift tax intact with a maximum rate of 35%.

Gift planning tools that result in welcome income tax savings, asset management, and more stable sources of income will have greater appeal than ever after the elimination of the estate tax. Persons who would be inclined to leave a gift at their death may be more likely to give during their lifetimes in ways that result in current tax savings and other benefits. Gift annuities, charitable remainder trusts, and gifts of remainder interests in homes and certain other real estate are examples.

Gifts in the form of charitable lead trusts that result in significant gifts over a period of years, while ultimately transferring unlimited amounts free of gift tax, will also continue to hold great appeal for wealthy donors in the wake of an elimination of the estate tax.

Charitable gifts of retirement plan assets during lifetime and at death will remain a wise option. These assets are now potentially subject to both income and estate tax. If the estate tax is eliminated, income tax will continue to be due on the amounts left to heirs from retirement accounts. For that reason, it will still be prudent to direct amounts remaining in retirement accounts to charitable use and leave nontaxable assets to other heirs.

There are untold billions of dollars outstanding in life insurance policies in America. Many of these policies are maintained for the purpose of paying estate taxes on real estate, businesses, art collections, and other illiquid assets. If no estate tax is due, the windfall in many estates will come in the form of life insurance policies that are no longer needed for their original purposes. With the jury still out on whether estate taxes will be eliminated for everyone, a wealthy individual would be ill advised to allow insurance policies to lapse. These persons might leave all or a portion of the insurance policies to their charitable interests if they are no longer needed to pay estate taxes on the amounts left to their heirs.

Conclusion

No one knows what will eventually happen to the estate tax liability that remains in place for the wealthiest Americans. We do know that for now the estate tax is gone for the vast majority who pass away in 2006 and in coming years. With proper perspective, nonprofits can encourage their donors to take advantage of this newfound wealth to make an even greater impact on their charitable interests. Funds previously redistributed involuntarily by the government through estate taxes can now be thoughtfully divided on a voluntary basis between family and charity. Now more than ever, the mission of your nonprofit organization or institution matters most as donors decide how to vote with dollars they have inherited or accumulated themselves.

1 This reference and others references to Congressional Budget Office statistics refer to Revenue Option 41, which may be accessed through the CBO Web site at www.cbo.gov.

2 Schervish, Paul G. and John J. Havens. “The Mind of the Millionaire: Findings from a National Survey on Wealth with Responsibility.” New Directions for Philanthropic Fundraising. 32 (Summer 2001): 98.