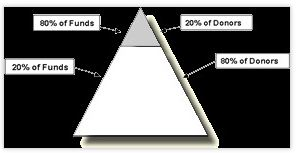

Those who have been involved in nonprofit fund development for a period of time may have seen a pyramid that is sometimes used to illustrate the distribution of gifts that might be expected as a result of a well-executed fund-raising effort. The premise is that the majority of gifts will primarily come from a broad base of donors, while the majority of dollars will usually come from a relatively small group of persons:

From that point, the discussion typically proceeds to address a number of important factors. How does one discover the handful of key donors? How do we motivate them to give? Who should ask them to give? How should they be recognized? How should their gifts be valued? In some cases, the pyramid will be capped off with planned gifts. All too often, however, little attention is paid to what donors should give, when they should give, and how they should effectuate the transfer of funds.

Over time we have observed that those who enjoy the greatest success in major gift development succeed in part because they spend the time necessary to learn and understand not only the “who” and “why” of the gift, but also the “what,” “when,” and “how” of the giving process.

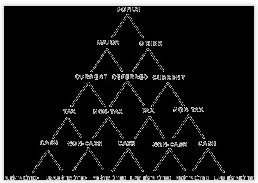

This can sometimes be easier said than done, however. With all the elements that can converge in the process of effectively planning a charitable gift, even the most experienced fundraiser can easily become overwhelmed. This need not be the case. To help organize thinking about the gift planning process, we have proposed another way to consider the traditional funding pyramid. What we refer to as a “Planning Pyramid” provides a helpful framework from which to view the art of helping people give.

In today’s environment, when the need for planned giving may be greater than ever, it is important that we think of planned giving as a process that can be rationalized. While there are any number of ways to think about the process of planning a gift, we believe that the planning pyramid described here may be a useful place to begin when analyzing a particular situation. Every gift works its way through the pyramid. The most successful organizations and institutions are ones that are prepared to help a donor and their advisors work their way through the process.

Sizing up the gift

Let us start with the premise that all gifts can be broken down into two broad categories—“major gifts” and “other gifts.” For most organizations and institutions, the vast majority of gifts will fall into the “other” category, with a relatively small number of major gifts each year comprising a relatively large percentage of overall funding.

The first step for a donor, after deciding to make a gift, is to consider whether he or she would like to make a large gift or a small gift. These terms are, of course, relative to the donor’s means, with some persons considering $1,000 to be a “major” gift while others see that as a relatively modest, “token” gift.

The timing element

The next step in the process is timing. Some persons who are capable of forming the donative intent to make a major gift are able to complete the gift right away. Others may wish to make a larger gift but, because of various financial circumstances, do not believe they are in a position to make the gift immediately. In that case a donor may decide to defer the gift for a period of time. The gift may be deferred for a short period of time (such as a pledge to a campaign over a number of years), or it may be deferred for a longer term of years or even for the lifetime of one or more persons (a bequest or gift with retained income).

Smaller gifts may also be made on a deferred basis. An example might be a donor who, when asked by their attorney if they have charitable interests, replies that they would like to divide the remainder of their estate, if any, among a number of charitable interests after first providing for a number of loved ones. In that case the donor may intend for a relatively small amount, if anything, to eventually be devoted to charitable use.

Tax considerations

After deciding how much to give and when, it can be wise for a donor to consider the tax consequences of the gift.

Note that larger and smaller gifts, whether current or deferred, may or may not be made in light of tax considerations. Consider the case of a donor with assets of $10 million and an adjusted gross income (AGI) of $300,000 who made a $250,000 gift of appreciated securities to a charitable interest last year. That donor would have been allowed to deduct just $90,000 last year (due to the 30% of AGI limitation for gifts of appreciated property). The donor would be able to carry over and deduct another $90,000 this year, leaving $70,000 to carry over and deduct next year. Now suppose that this donor has also made cash gifts this year that bring him up to the total of 50% of AGI limitation. For him, if he were driven strictly by tax considerations when considering whether to make an additional gift of any size, he would not make it, for it would not be deductible and would have to be made from after-tax income.

Experienced fundraisers know that donors will sometimes make a gift regardless of their inability to deduct it. A wealthy donor may have a large amount of tax-exempt income that is not considered part of his or her AGI and will use cash from this source to make a gift. Not reporting the income and giving it away with no tax deduction is equivalent for tax purposes of reporting the income and then taking a charitable deduction.

In the case of most donors of small amounts, their charitable gifts do not exceed the amount of the standard deduction and are thus not deductible for income tax purposes. This is the reason tax considerations do not come into play for many smaller gifts.

While it can be a serious mistake to overemphasize tax savings to those who are not motivated by this aspect of charitable giving, it can be an equally damaging error to ignore tax considerations when dealing with donors or their advisors for whom this factor is crucial. In fact, after consideration of tax savings, some donors may actually decide to increase the size of the gift they originally planned to make. Maintaining perspective and balance is key when addressing the role of taxation in charitable giving.

What to give?

Tax and other financial considerations can also help a donor decide the type of property used to make the gift.

Once a donor has decided to make a large or small gift, whether current or deferred, the donor must decide if the gift should be made in the form of cash or other property.

The larger a gift, with or without tax considerations, the more likely it is that the gift will be made in a form of property other than cash. Where donors are in a position to take advantage of the capital gains tax savings inherent in gifts of appreciated assets, this form of property will often be the “gift of choice.” In other cases, donors will sell assets that have declined in value, take a capital loss, and make their gift in the form of cash that is subject to the 50% of AGI limitation.

Avoid the common mistake of thinking that donors always make gifts of appreciated property for tax savings purposes alone. Imagine that a donor owns 20 investment properties worth an average of $500,000 each that in total are worth $10 million. If the donor wanted to make a gift of $500,000, with or without tax considerations, would the donor be more likely to give cash or one of the properties worth $500,000? It would depend, but one can imagine a situation where the donor did not have $500,000 in liquid assets readily available and decided to instead transfer one of the investment properties in satisfaction of a pledge. In our experience, donors sometimes give what they have, regardless of tax consequences. Most wealthy donors do not become wealthy or stay wealthy by keeping hundreds of thousands of dollars in checking accounts. For this reason, asking for larger gifts is usually tantamount to asking for a non-cash gift.

Why is the gift made?

Finally, we come to the “why” people give, i.e., for what purpose. Any of the previously described gifts can be for restricted or nonrestricted purposes. The reason for the gift can sometimes affect the timing. For example, a donor who would like to make a large gift for endowment and long-term security of the charitable recipient may be more likely to make a gift on a deferred basis than a donor interested in funding an immediate need. A donor interested in funding an urgent mission might also, on the other hand, consider a charitable lead trust as a way of funding a pledge of a “current” gift over time while “deferring” a gift to family members who may have longer term need for the funds. Avoid confusing the “why” with the “what,” “when,” and “how” of the gift.

Using the pyramid

Most gifts in terms of sheer numbers will work their way down the right side of the planning pyramid. They are smaller, current, non-tax-oriented gifts of cash for unrestricted purposes. Contrast this with a larger, current, tax-oriented gift of cash that is restricted for a capital project. Most organizations are more familiar with and better able to work with gifts that travel down one slope of the pyramid or the other.

In an environment characterized in many cases by an aging donor base, investment uncertainty, and other challenges, the most successful development efforts in coming years will be the ones that have developed the capability to navigate the various courses a gift can take through the center of the funding pyramid.

For instance, many organizations have well-honed annual or more frequent efforts to raise small, unrestricted, cash, non-tax-oriented gifts for immediate use. Others conduct periodic campaigns for larger, restricted gifts of cash or other property that come from persons who may be motivated to some extent by tax savings and are willing to defer the gift for no longer than a limited pledge period. Many organizations and institutions also conduct campaigns for gifts that are restricted for “endowment” and are expected to come in the form of larger tax-oriented trusts and other deferred gifts or from non-tax-oriented bequests from donors of more modest means.

Alongside all of these efforts we often find planned gift development efforts designed to help donors make all of the gifts described above more effectively.

Start at the top

It has been said that the only place one starts at the top is when they are digging a hole! An exception to this may be the planning pyramid.

Understandable confusion and overlap of efforts can result from starting at the bottom of the planning pyramid with outcomes and working upwards in an effort to find donors at the top of the pyramid who are willing to fund various types of gifts that are desirable from the perspective of the charitable recipient.

Note that the donor—not the institution—is at the top of the pyramid. It is important to have various types of programs that are designed to produce funds for different needs at different times and make services available to donors that help in the process of planning their gifts. The most successful programs, however, are those that do not lose sight of the process of making a gift from the donor’s perspective. Imagine yourself at the top of the pyramid and the reactions you might have as you perceive numerous initiatives working their way up the pyramid toward you.

The planning pyramid is designed as a mental tool to help fundraisers organize their thinking in light of their donors’ perspectives. The key is to make all the various means of making gifts available and work to the extent possible to help the donor choose the most appropriate way to make a gift in their season of life. It may thus be wrong to think of “planned gifts” as deferred gifts, as property gifts, as endowment gifts, as tax-oriented gifts, or as primarily taking on the characteristics of any of the numerous outcomes possible at various decision points in the planning process. Planning charitable gifts is a process. The “planned gift” is the outcome from the institutional perspective. “Gift planning” describes the process from the perspective of the donor.

In the March 1988 issue of Give & Take, we put forth the following definition of “planned giving”:

“A planned gift is any gift of any kind for any amount given for any purpose—operations, capital expansion, or endowment—whether given currently or deferred if the assistance of a professional staff person, qualified volunteer, or the donor’s advisors is necessary to complete the gift. In addition, it includes any gift which is carefully considered by a donor in light of estate and financial plans.”

We stand by this definition today. Planned giving is not the sale of products. Planned giving is not promotion of tax gimmicks. Planned gifts are not financial “special events” with only tangential charitable benefits. Planned giving is simply the process of transferring income and/or assets from motivated donors to worthy charitable recipients in the most expeditious and cost-effective ways possible in light of a donor’s circumstances. We trust the planning pyramid will serve as a helpful road map to assist donors and their advisors as they thoughtfully consider their gifts.

Editor’s note: This article is based on Session 3 of the popular Sharpe seminar Major Gift Planning I. Click here for upcoming dates and locations.

An 8.5 x 11 depiction of the planning pyramid may be downloaded from www.sharpenet.com/pyramid.