While gifts of cash are the largest source of charitable gifts, experienced fundraisers have long known that larger gifts are much more likely to come in the form of assets other than cash—most often gifts of marketable securities. For example, the Council for Aid to Education (CAE) reported that the average stock gift to higher education in 2003 was $34,219. Charitable remainder trusts, gift annuities, and similar gift planning arrangements are also regularly funded using assets other than cash. It is important, therefore, that fundraisers be aware of the manner in which donors, especially those with significant assets, hold their wealth.

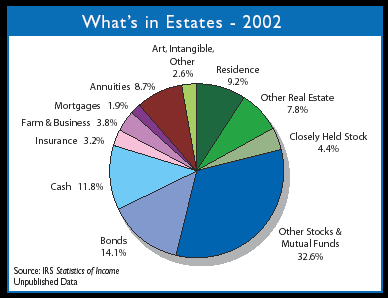

The Internal Revenue Service periodically releases statistics on the composition of taxable estates based on estate tax filings as part of its Statistics of Income series. The most recent data covers estate tax return filings for 2002 and appeared recently as unpublished online data. This information serves to shed light on the composition of asset holdings of the wealthy at the time of their deaths.

Here’s a look at the latest figures:

Little change in stocks

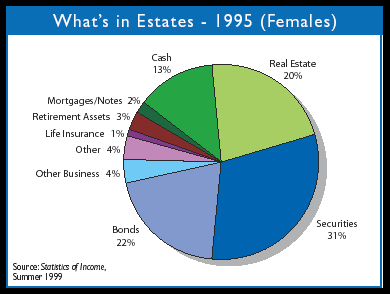

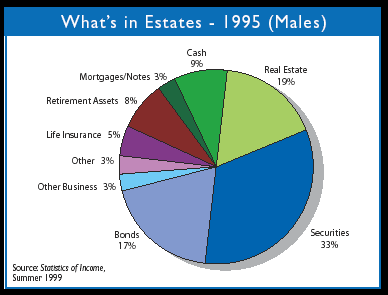

The first impression on viewing the information from 2002 estate filings is how little change there has been since similar data from estates filed in 1995 was published. In 1995, 33% of the value of estates owned by males was held in the form of publicly traded stocks and mutual funds. The figure was 31% for estates of females. This is remarkably close to the 32.6% figure reported in the 2002 data, which was not broken down by gender. See page 5 for a breakdown of 1995 data.

Keep in mind that these figures represent assets held at the time of death. According to IRS data, the majority of those with taxable estates pass away in their late seventies and early eighties.

One lesson to be drawn from this information is the importance of emphasizing gifts of securities among even the oldest donors. When illustrating large trusts and other planned gifts in proposals for older donors, examples of gifts funded with appreciated securities may be especially appropriate.

As donors grow older, they can become more risk averse in their investments. It may be wise to encourage donors to give stocks that they believe may present greater risk of loss, benefit from capital gains tax savings, and then make use of cash they might otherwise have given to diversify their position in the market.

What about bonds?

In 1995, bonds represented 22% of estate value for females and 17% for males. Why the difference? In that year, the age at death for the females whose estates were represented in the data was 80.9, compared to 75.3 for the males. As a general rule, as one ages, the more conservative investments generally become. Regardless of gender, older investors tend to have relatively less tolerance for the risk associated with investments in stocks. Because women typically outlive men, it makes sense that the estates of women have a higher concentration in bonds.

By 2002, however, we see a substantially lower percentage in bonds in taxable estates—down to 14.1%. Part of this decrease may be attributable to the lower interest rate environment in 2002. As interest rates fall, new bonds generally become less attractive.

The decrease in bonds may also be a result of the 2001 Tax Act and other legislation. The 2001 Tax Act increased the threshold for estate tax liability from $600,000 in 1995 to $1 million in 2002. Consequently, the estates included in the 2002 figures represent individuals with higher net worth. Affluent persons are more often willing to tolerate risk by holding more of their wealth in the form of stocks later in life.

Additionally, the 2002 data is broken down differently than the data in the 1995 report. In the 2002 report, annuities were listed in a separate category and constituted 8.7% of the estates. In 1995, annuities were not reported separately. But if we consider annuities to be a relatively conservative, fixed-income investment closer in character to bonds than to stock, then summing annuities and bonds in 2002 gives us a figure of 22.8%, which is not far from the 22% in bond holdings reported for females in 1995.

Although this data suggests bonds may make up a smaller portion of the assets held by wealthy older per-sons, giving bonds still may be a viable option for many donors. While interest payments from existing bonds have remained the same, the value of many long-term bonds has gone up during extended periods of lower prevailing interest rates. Some donors may thus wish to lock in today’s value and possibly increase their yield through a life income arrangement while avoiding or delaying capital gains tax that might otherwise be due.

Real estate

The 2002 data breaks down real estate by value of residences (9.2% of the estates) and other real estate (7.8%), for a total of 17%. This is comparable to the figure of 19% to 20% for the value of real estate in 1995 estates. The fact that it is a little lower despite increased real property values in many parts of the country is again most likely because the 2002 data represents the estates of wealthier individuals. For many persons whose estates were within the lower threshold for federal filing in 1995, it is very likely that the percentage attributable to real estate, especially the personal residence, was substantially higher than was the case for those with taxable estates at or above the higher filing threshold in 2002.

The value of principal residences and second homes has indeed risen for many people in many areas of the country, but as values rise dramatically fears that the “bubble” might be about to burst begin to emerge. Consequently, gifts of marketable, high quality real estate, either on an outright basis or with a retained life estate, may increasingly represent a viable option for older donors with substantial other assets who wish to obtain maximum value from real estate they believe may have peaked in value for the foreseeable future.

Cash and implications for development efforts

As stated at the outset, cash makes up a relatively small portion of estate value. In both 1995 and 2002, cash accounted for between 9 and 13% of taxable estate value.

The implications for those managing development efforts are clear. Most people who accumulate substantial amounts of property during their lifetimes do not leave much of it sitting in the form of cash in checking accounts earning little or no interest and being eroded by inflation.

Despite this simple truth, many nonprofits devote the majority of their attention to asking their supporters for gifts of cash. As a result, the IRS data makes it clear that when working with persons of substantial means, more than 87% of the value that might potentially be given to support worthy programs may be ‘left on the table.’ Even the most basic gift planning marketing effort can offer viable alternatives for many donors.

In conclusion, it is important to point out that the data for both 1995 and 2002 are drawn from a very small minority of estates—those subject to filing an estate tax return, whether or not tax was ultimately paid. For 2002, 98,359 filed an estate tax return and of those only 44,407 owed federal estate tax. These figures are compared to the more than 2.4 million deaths in the United States in 2002.

While little information exists for estates not required to file a return, it is reasonable to assume that the less wealthy would also tend to hold a minority of their property in cash. It is likely that the share devoted to real estate would be somewhat higher and the portion held in securities would be lower than in the estates of the more affluent group of filers.

Give & Take will continue to monitor IRS and other data and follow up with future reports.