By: John Jensen

You probably have a plan in place for what should happen to your investment accounts, retirement fund, real estate and other property when you pass away, but do you have a plan for who gets your e-book or iTunes library or what happens to your Facebook page? Have you entrusted someone to access your online accounts? Probably not. And your donors probably haven’t either.

You probably have a plan in place for what should happen to your investment accounts, retirement fund, real estate and other property when you pass away, but do you have a plan for who gets your e-book or iTunes library or what happens to your Facebook page? Have you entrusted someone to access your online accounts? Probably not. And your donors probably haven’t either.

Going digital.

Think of the photos you have taken in the last five years. You have probably printed only a handful. The rest exist only in digital form—either on your hard drive, on your phone, on social media sites or in cloud storage.

Our financial and estate documents have taken a similar path. Until recently, the information we used to organize our estates existed on paper, and, provided we planned accordingly, our executor or heirs would have had no problems accessing them. However, in recent years our records have become increasingly digital.

In many ways, the digital world has helped us better track and access our accounts and affairs, but it’s a potential nightmare for our executors and loved ones. When considering our digital records and assets, bank, brokerage, retirement and other financial statements are just the start. Most of us have multiple email addresses, cloud-based photos and videos and online frequent flyer or credit card loyalty accounts, not to mention the passwords needed to access our PCs, smartphones, iPads and e-book libraries. Some of us even own bitcoins or other payment accounts held in the digital wallet app contained on our smartphone or PC.

Back where we started.

Ironically, in today’s world there may be a real need to do your digital estate planning on paper—even if it’s only a printout of a digital record. Start by creating an inventory. Write down each digital asset, what it is, what the web link is to get to it and your username and password. This will almost certainly require several sessions, since most of us will not be able to think of them all in one sitting.

Next, find a safe place to keep this information, such as in a bank safe deposit box or with the attorney who prepares your written will. This contains very sensitive information, so it needs to be handled carefully. Not surprisingly, there are also commercially available “digital lockboxes” to gather and store such information. There’s also the option of a password manager program—provided that you give someone the location and password to access it.

Name a “Digital Executor” in your written will. This might be the same executor you name for your written will, but does not need to be. This may or may not work in every case, but it provides a starting point. Explicitly state that this person has the authority and responsibility to deal with your digital assets and to carry out instructions you may have provided.

Keep in mind that your will becomes a public document at death, so this is not the place to include passwords. Better to use the will to refer to an outside document if necessary.

Deciding the fate of your digital assets.

The next step may be more difficult. Decide what you would like done with your digital assets. Some of these assets can be given to multiple people. What about the photos of your family and friends? Would you like to prepare something to be sent out on Facebook after your passing?

The next step may be more difficult. Decide what you would like done with your digital assets. Some of these assets can be given to multiple people. What about the photos of your family and friends? Would you like to prepare something to be sent out on Facebook after your passing?

Social media sites have begun offering options for a deceased member’s account. Google has created an “Inactive Account Manager” to automatically notify someone of your choosing if your account is not accessed or updated for a period of time. This can involve just a notification or can pass on more detailed information. Facebook has an option to memorialize or deactivate an account of a deceased loved one.

Other digital companies will undoubtedly follow suit, but each will have its own quirks and nuances, and most have strict rules about not sharing account login information even after you have passed away. Additionally, finding the fine print or contact information can be difficult. If your executor has the login and password in hand, it may be a simple matter for him or her to handle directly. Company policies vary widely, and most states do not yet have specific laws to address these situations.

Some digital assets may be passed on to family members, while others cannot. Other rights are still murky. For example, you may not be able to pass on your e-book licenses, but you may be able to give away a Kindle or other e-reader that contains the rights to those same books. The same holds true for digital music libraries like iTunes.

Help your donors stay organized.

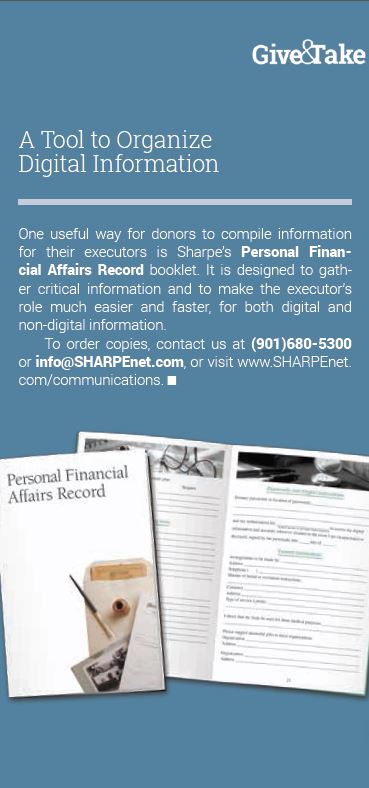

Consider sharing tools with your donors that help them organize their digital affairs [see box at right]. Printed information may be more useful than an online approach.

Anything that helps get donors organized and speeds along the process of updating their estate plans is far more apt to increase the likelihood that the charity providing the service will end up in those plans.

While most of us have not given much thought to our digital estate, the time to do so has certainly arrived. If you have not made your plans, the resulting problems can be painful and costly for your loved ones. Without question, the need for this will continue to grow over time. ■