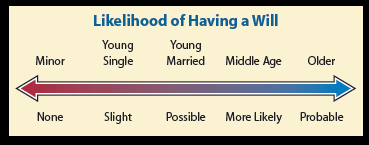

It is a well-established fact that the majority of adults have not taken steps to draft even the most basic last will and testament. A number of factors, including wealth, education, religion, age, and marital status, can help determine whether or not an individual is likely to have a will or other estate plan in place. To a certain extent, the likelihood of having a will and the probability of having a provision for charity follow a relatively predictable timeline.

This is their life

While it is a matter of state law, in most cases persons under the age of 18 may not create a will.

To have a will, an individual must legally be an adult with sufficient mental capacity as determined under state law.

Drafting a will is not a high priority for those in their late teens or early twenties unless they are in the military and are required to do so prior to going overseas. Even then, whatever assets they own—most often employer-sponsored life insurance and retirement plan funds—are likely to pass by beneficiary designation. If the individual is unmarried, parents or siblings are likely to be the primary beneficiaries of the estate. The number of deaths per thousand is very low in this younger age range.

At this early stage of life, charitable bequests, if any, are relatively rare and likely to be small because few persons at this young age have accumulated much net worth. A small specific bequest, typically a few thousand dollars at most, may be considered. Occasionally, a charity may receive all or a portion of a small retirement plan balance or life insurance policy.

Many young people in their twenties and thirties choose to marry and trade apartment life for a home or condominium. It is not uncommon at this point for net worth to become “negative” because of mortgages, automobile loans, and consumer debt.

Very few individuals at this age have wills because asset transfer in the event of premature death has already been arranged by joint ownership, beneficiary designation, and state laws that would typically favor a surviving spouse. Any charitable estate gifts are still most likely to stem from contingent beneficiary designations on life insurance policies or retirement plans.

Married with children

Once a couple has children, things get more complicated. Estate plans must now resolve issues such as guardianship of minor children, potential distribution of assets under state law (a surviving spouse might end up receiving only a fraction of the decedent’s estate if there are children), and other considerations. Often additional life insurance is purchased to provide for a spouse or children in the event of the death of one or more of the family’s breadwinners. Most charitable gifts take the form of smaller current gifts out of income because asset accumulation is still in its early stages.

People in this age range may seriously consider the need for a will or trust to provide for a surviving spouse or children. Those who are single may still rely on joint ownership or beneficiary designation. If a will is drafted, any charitable provision is likely to be either a relatively small specific bequest or a gift contingent upon some remote occurrence such as a disaster that may affect the entire family.

Worth more dead than alive?

During their thirties and forties, many adults are earning more than ever before. As children grow older, it becomes more common for families to have multiple wage earners. Average net worth is still relatively low, but may begin to grow as savings and investments accumulate and debts are paid off.

The composition of wills done at this stage of life normally continues to focus on the needs of a surviving spouse or children. Those who are single or childless may shift the focus to parents, siblings, or nieces and nephews. For the most part, any charitable provision is still likely to be a relatively small specific bequest or one that is contingent on the premature death of one or more persons.

Mid-life priorities

In one’s mid-forties, fifties, and sixties, most people are likely to be at the peak of their careers and may be earning more than at any other point in their life. Those who have managed to accumulate any significant wealth are faced with multiple estate, gift, and financial planning considerations, most notably the need to provide for oneself and one’s family. A small group may have sufficient income and assets to feel comfortable making or considering larger gifts now or in the future. A smaller subset of this group may even be in a position to consider a relatively larger specific bequest of $25,000 or more. Those in this age range who have a will or other estate plan in place are still in the minority, and charitable provisions for the most part remain contingent on the prior death of one or more parties. For example, a couple without children may have wills leaving everything to one another but then to charity upon the death of the survivor or in the case of a common disaster. The number of people that would at least consider a charitable bequest may be large, but most decide against making a gift because they feel there are not yet enough assets to provide for family, friends, and charity.

The later years

Most people retire in their sixties or early seventies. For many, their net worth has never been higher. Even though their net worth is at a peak or may continue to grow, after retirement the loss of earned income may affect an individual’s ability to give the same amount to charity as before. In addition to the loss of discretionary income, family assets may need to last for two or three decades longer given today’s life expectancies. Estate planning begins to take on a greater importance, and the number of persons who have a will, trust, durable power of attorney, and healthcare directives grows with each additional birthday.

Those who have adequately provided for their loved ones can now seriously consider including charities in their estate plans. As parents, grandparents, perhaps older siblings, spouses, or even children begin to pass away, the number of potential heirs decreases, which increases the chance that provisions will be made for friends and charities. IRS data and other studies show that the likelihood of a charitable bequest and the percentage of the estate left to charity both increase as people age into their seventies, eighties, and nineties.

The most common candidates for charitable bequests are older persons who never married or had children. Couples without children or those whose children are well off are also good prospects. In the case of a couple, the operative last will and testament for charitable purposes is usually drafted only after the death of a spouse. This final will is increasingly being drafted relatively late in life.

Fool’s gold or the real thing?

In an ideal world with unlimited resources, charities should make their entire constituency aware of all of the various ways donors can support their work. However, in today’s world of limited funds, those devoting significant human or financial resources to encouraging estate gifts from younger and middle-aged donors are likely to be greatly disappointed.

One national charity that has aggressively pursued such a strategy over the past decade while reducing the emphasis on older donors recently revealed that it had identified over $1 billion in pending planned giving expectancies. While that figure sounds impressive, the charity’s actual planned giving revenue has declined almost every year from the level reached in 2000. Had the charity focused limited resources on targeting their older donors first, it may have been able to simply maintain its previous level and would have received significantly more in actual planned giving revenue.

Know your donors

By limiting the marketing of bequests to older donors who have both the incentive and the means to make a substantial estate gift in the short term, charities can feel secure they are making the best use of limited time and resources for maximum impact. For this reason, fundraisers should make an effort to discover relevant information about their donors, including age, marital status, and other important statistics. Without this information, it can be difficult to segment your donor base so that you know you are sending the most appropriate material to each potential donor. Time is money. Make sure you are a good steward of your organization’s time and money by making informed decisions.

Note: This article was excerpted from the popular Sharpe seminar “An Introduction to Planned Giving.”