Paying attention to the donor life cycle can pay off.

Paying attention to the donor life cycle can pay off.

One of the most frequently cited myths about fundraising—and a reason why many gift planners face resistance from their peers involved in other individual gift development efforts such as annual giving, membership and major gifts—is the belief that planned giving can interfere with other giving. That is, some people believe that reaching out to donors in ways designed to encourage the “gift of a lifetime” will cause them to reduce or even completely stop making other gifts.

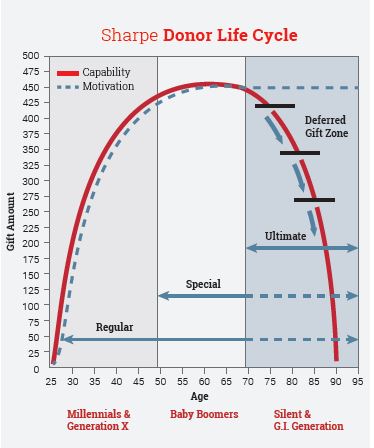

The truth is, most donors follow a typical “life cycle” in which bequests and other gifts through one’s estate can play an important and natural part. Research shows there is a natural relationship between the donor’s age and the types of gifts the donor chooses to make. Older donors, when facing reduced income and increased healthcare costs, sometimes cut back on outright gifts during their retirement years, whether or not they have an organization named in their estate plans.

The key to keeping donors actively involved in later years lies in recognizing their stage in the donor life cycle and sharing gift opportunities that will speak to their changing concerns and needs.

The early years.

In the Early Years, for our purposes those under age 50, people typically are at the onset of their careers. Many are starting families and purchasing homes while also repaying student loans. Donors at this age are prospects for regular gifts and are often open to new ways to make gifts. They are more likely to respond to online solicitations using credit and debit cards. The fundraising focus is mainly on donor acquisition, retention and gradual increases in gift amounts. This group of donors is made up of Millennials and Generation X.

The middle years.

Regular giving continues during the Middle Years (for our purposes ages 50-69). For many, this is the most generous stage of their lives. This age range now encompasses virtually the entire baby boom generation. Many are in their peak earning years and may have more discretionary income and assets than ever before. Some of these loyal contributors may be able to make major or special gifts, often in the context of a campaign. Most are not yet considering their ultimate gifts as they are anticipating a life expectancy of 20 to 40 years or more.

The later years.

As noted earlier, in the Later Years (70+), some donors begin to decrease their regular outright giving as their income falls and health expenses rise. People in the later stages of life may be considering making their ultimate gift. The ultimate gift is defined as the largest gift a person is capable of forming the donative intent to make. Motivation to give often remains high, but the ability to give as they did in the past can be under pressure.

It is inevitable that most donors, even major donors with significant amounts of assets, will begin to reduce or stop their giving at some point prior to death. The most successful development programs incorporate efforts designed to anticipate and control this process to the extent possible. While proven methodologies exist for the acquisition, retention and upgrading of donors, few organizations have considered developing tactics designed to manage what for most donors will be an inevitable “downgrade.”

The real choice is not between a current gift and a deferred or planned gift. Rather the choice is between participating in the donor’s ultimate gift decisions or no gift at all as every donor will eventually stop giving. The most effective fundraisers will pay attention to each donor’s stage of life and work with him or her to make the most appropriate gift at the most beneficial time to create the kind of lasting legacy the donor desires. ■

Excerpted from Sharpe Group’s seminar “Integrating Major and Planned Gifts.” For more information, click here.