In times of economic prosperity characterized by large amounts of discretionary income and capital, fund raising activity tends to focus on the basics: planning and organization, training and motivating volunteers and staff, tracking progress, acknowledging gifts, and stewarding ongoing relationships. In good times, gifts are often presumed to be primarily motivated by the donor’s desire to support the mission of a particular organization or institution. For those with a strong case for support, asking for gifts from enough people, often enough, on a consistent basis, normally leads to results that are at least acceptable, if not exceptional.

Today, however, the “wealth effect” of the 1990s has subsided and provides less impetus for across the board increases in giving. The most successful programs are beginning to more closely examine why individual donors have given in the past and, more importantly, how they may be motivated to give in the future. While examining the reasons for past generosity can offer some indication of the likelihood of future giving, personal priorities and values can and do change over time. Donors may require different and in some cases more compelling reasons to give when demands on their capital seem to come from every direction.

What motivates a gift?

Unfortunately, there is no simple answer. People give for many and varied reasons. Although those outside the world of development may assume that donors give primarily to gain recognition or tax savings, those desires are only part of the picture. What are the other motivators?

Religion appears to inspire more charitable gifts than any other motivation. In fact, the majority of charitable gifts in America each year are designated for religious-based charities. According to the Giving USA report, charitable organizations with religious affiliations received nearly 40% of all charitable gifts in 2001.

By comparison, education and health care combined accounted for just 24% of individual giving.

Despite the personal nature of religious beliefs, successful fundraisers should make every effort to understand them and their role in the gift planning process if they want to help their donors make their gifts most effectively. For instance, in a number of religious traditions, it is possible to achieve the greatest satisfaction in giving only by making gifts anonymously.

With such a donor, offering a naming opportunity or otherwise emphasizing recognition for a gift may actually seem insensitive and may even be offensive to some.

Social motivations are another major factor that influences charitable giving behavior. Many donors who are not motivated by religious beliefs hold definite ideas regarding social responsibility that include the duty to share with others and to invest in social infrastructure.

It is often the case that persons who have accumulated or inherited substantial wealth believe they have an obligation as part of a “social contract” to help meet the needs of society. Philanthropy has long been one of the behaviors expected of those who would be community leaders and members of influential social circles in a culture built on a combination of democracy and capitalism.

Political beliefs can also come into play. Some persons are adamantly opposed to government taxation and spending for social welfare and cultural purposes. Within that group are the “social Darwinists” who believe in “survival of the fittest.” Others, however, believe that they are “stewards” of capital and have a duty to reinvest it for the benefit of mankind through a voluntary system of wealth redistribution. Still others believe in European-style social democracy with involuntary redistribution of wealth through high taxes, universal government benefits, and little or no private philanthropy. Understanding where donors fit on the political spectrum can be a key to helping them decide whether, when, and how to make their gifts.

A discussion of the many emotional motivations for charitable gifts could fill volumes. Virtually every human emotion can inspire a charitable gift. Gifts in memory of or in honor of others are obviously emotionally charged (see page 3). Quite different emotions may motivate donors who wish to gain recognition or notoriety for themselves through their gifts.

Other gifts can be guided by a combination of emotions. Consider, for example, the complex forces at work in the mind of a man who has been asked to make a major gift to a university medical facility. This university is pursuing state-of-the-art research on a genetically linked disease that has already taken the life of his wife of 40 years—research that may in the future save the lives of his own children.

Suppose the same institution recently announced a decision to condone behavior on campus that the donor finds morally objectionable. Experienced development officers appreciate the challenges such conflicting emotions can present and will work to obtain a mutually agreeable outcome.

Because emotions can be so powerful, it is tempting to overemphasize them at the expense of other factors that may be more relevant. The key is to find a way to understand and satisfy donors’ emotions and desires without manipulating those persons who may be at their most emotionally vulnerable, particularly older donors and those who have recently lost a loved one. As a result, this is one of the areas of fund development in which experience, personal integrity, maturity, and judgment are especially important. Board members and development officers should seek out these characteristics when hiring staff with planned and major gift responsibilities.

Lastly, economic quid pro quo is perhaps the most misunderstood motivator of charitable gifts. While it is true that there are significant tax and other financial benefits associated with certain types of gifts, it may be an increasingly dangerous mistake for fundraisers to assume that these factors are more than occasionally the root motivator for gifts. Remember that donors receive the same tax benefits regardless of the recipient of their charitable gifts, and most nonprofits offer the same or similar payment rates.

This is why, at the end of the day, planned gift marketing activities based solely in tax and other benefits seldom produce meaningful or long-term results. In fact, such efforts may simply serve to educate donors who then decide to complete gifts with other charitable interests that satisfy their true donative intent.

Herein lies the paradox. In today’s world of major gift development, it is vital to understand the economics of larger charitable transfers, but it is also important to realize that those economics in the end rarely motivate the gift itself. A study commissioned by NCPG in 2002 affirms this fact (see page 3).

The most successful gift planners know the importance of non-financial motivations and thus tend to put the “gift” before the “plan.” They know it is difficult if not impossible to transform even the best “what,” “when,” and “how” into the “why” behind the gift.

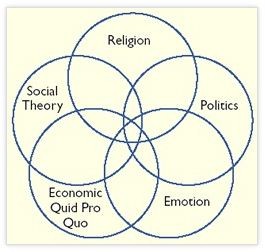

The interconnection of the motivations discussed above illustrates how rare it is to find a single motivation as the sole reason behind a gift. Most larger gifts tend to involve complex relationships between a number of these factors. Understanding the “motivational molecule” depicted above is a major key to successfully arriving at the correct gift solution.

Completing the puzzle

After fundraisers develop a greater understanding of the basic motivators for charitable gifts, the other pieces of the puzzle tend to fall into place. The property that a donor uses to make a gift may be decided upon in part by economics, in part by emotion, and in part by other considerations. A similar combination of factors usually determines the timing of a gift.

The property and timing, when decided, then naturally tend to drive the process toward a particular gift planning vehicle. In times when donors are perhaps more likely to closely scrutinize requests for gifts, fundraisers would be wise to devote more energy to gaining a better understanding of why donors give. Learning about gifts donors may have made in the past can shed some light on their motivations. In the final analysis, however, there is no substitute for carefully maintaining relationships with donors over time. That is the best way to learn about motivations that are not detectable through electronic screening and other impersonal means.

The best laid plans

Even in the best of times, donors will sometimes express reluctance to make a gift in the context of a capital campaign or other fund development effort, in spite of earlier expressions of interest and careful analysis of a donor’s motivations and the other components of the gift. What then?

In this article we have explored some of the basics of why donors make gifts. Next month, we will examine the reasons why otherwise motivated donors will sometimes decide not to make a gift, and how to respond in ways that can salvage gifts that otherwise might not come to fruition.

Editor’s note: This article is the first of a two-part series. Part II, entitled “Why Don’t People Give More?,” will be featured in the March issue of Give & Take. This article is based in part on Session III of the Sharpe seminar “Major Gift Planning, Part I.” See page 7 for upcoming dates and locations or visit www.sharpenet.com/seminars.