Even though retired households often enjoy significantly less income than working households, they tend to give more generously, according to preliminary results of a study being conducted by the Center on Wealth and Philanthropy at Boston College.

Highlights about retired households include:

- They earn 35% less than non-retired households

- They own 58% more wealth

- They contribute 69% more to charity

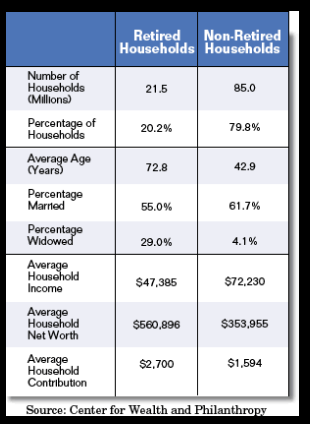

The study finds that one in five households, or 21.5 million, is considered “retired.” On average, the heads of these households are older than those of the non-retired household, at 73 versus 43 years of age respectively. They are also less likely to be married and more likely to be widowed. The retired households have an average income of $47,000 versus an average of $72,000 for non-retired households. Their average net worth of $561,000 is substantially higher than the $354,000 for non-retired households. Retiree charitable gifts average $2,700 per year while the non-retired households give an average of $1,594. Overall, the average contribution for all households is $1,817.

Although retired households represent only 20% of those surveyed, own 29% of accumulated wealth, and earn just 14% of the total household income, their charitable contributions comprise 30% of the total.

While 55% of the heads of retired households are married, 29% are unmarried women and 16% are unmarried men. Married retirees seem to enjoy the highest standard of living. Retired married households enjoy an average annual income of $63,000 and an average net worth of $793,000. In sharp contrast, unmarried female heads of households average $22,000 in annual income and $197,000 in net worth. According to the study, unmarried men fare better than their female counterparts, with an average household income of $41,000 and an average net worth of $428,000 per household.

These figures are based on data from the 2001 Summary of Consumer Finances, which is sponsored by the Federal Reserve Board. The study’s findings confirm earlier studies that have shown that retirees give more generously than the general population. This may be a function of the fact that, even though household income falls after retirement, discretionary income remains relatively high. The 43-year-old non-retiree may have a newer automobile, higher mortgage, more taxes, more dependents, and generally higher expenses. The 73-year-old retiree may drive an older vehicle, may have paid off his mortgage, may pay less in taxes, may have fewer dependents, and may enjoy generally lower fixed expenses. Additionally, retirees may have more time to contemplate and pursue their charitable giving and volunteer interests.

This retired group also represents the typical planned giving donor that might make a charitable bequest or be interested in a charitable gift annuity or other life income gift. The post-retirement group of average means and assets provides the solid core of many planned giving programs’ donors. Those average retirees with no or fewer children and those who have lost a spouse or were never married make up the bulk of planned giving maturities for most programs.

The next time you see someone asking for a senior citizen discount, recognize that you are probably looking at the backbone of American philanthropy and a possible planned giving prospect. Understanding their values and issues specific to their stage of life can help those in fund raising better serve this segment of their constituency. To learn more about this study, visit the Center on Wealth and Philanthropy’s Web site at www.bc.edu/research/swri/.