by Russell James

Professor Russell James, J.D., Ph.D., CFP® of Texas Tech University is responsible for the university’s on-campus and online graduate program in charitable financial planning. This month’s article is the second in a three-part series highlighting new findings from his latest research into the demographics of charitable estate planning. See the first story here.

Some recent studies suggest that younger people are typically more open than older donors to the idea of, at some point, including a charity in their estate plans. They are also thought to be more flexible in their preferences of charities. So, the argument goes, if a charity focuses on this younger age group, it could be the first to claim the estate planning “territory.” Assuming the charity stays in the donor’s plans, it should, eventually, see the financial rewards of these efforts.

The problems

Charitable plans change.

The new American Charitable Bequest Demographics publication 1 reports data from a longitudinal study tracking older adults and their estate plans. Because this data tracks the same individuals year after year, it provides the best information about how often plans change. For example, among those who initially reported having a charitable estate plan, 10 years later 45 percent reported no charitable beneficiaries remaining in their plan.2 Of course, even for those who continued to have a charitable beneficiary, their particular charitable interests may have changed. These changes tend to benefit charities that are of special concern to the oldest adults, demonstrated by the much higher percentage of estate gift income given to such causes.3

Charitable plans often change as death approaches.

Among the over 10,000 survey respondents who passed away during the study, two-thirds of all charitable estates and over half of all charitable estate dollars—came from those who reported having no charitable estate plan within five years of their passing. (Charitable estates represented about 6 percent of all estates.) Major triggers for both adding and dropping a charitable plan during life included diagnosis with a life-threatening illness, worsening health and approaching the date of actual mortality. Taken together, this indicates that charitable estate plans change dramatically as mortality nears. This is particularly critical because revocable charitable estate plans only have value to a charity at one point in time—at the passing of the donor.

Wealthy people live a long time. Wealthy bequest donors live even longer.

Total dollars from charitable estate gifts often come disproportionately from wealthy decedents. This is important because, in the previously mentioned demographics study, both wealth and having a charitable estate plan were associated with an older age at death.

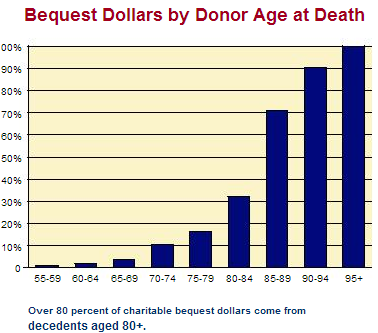

The accompanying chart , taken from the over 10,000 deceased survey respondents, shows that the bulk of all charitable estate gifts come from those passing in their 80s (with about 18 percent coming from those passing aged 55 to 79 and about 29 percent from those passing at 90 or older). Combining this with the knowledge that the majority of charitable estate donors added their charitable component within five years of their passing suggests that the most important decision-making time doesn’t start until age 75. Because the key age group for producing matured gifts is age 80 to 89, the most critical age for influencing these ultimate decisions is 75 to 89.

Some solutions

A realistic valuation.

When a donor names a charity in a revocable estate plan, the charity is a bit like a beneficiary of a term life insurance policy. In fact, we can use term life insurance rates to compare the relative annual value of being named in the estate plan of people of different ages. Buying a one-year life insurance policy for a healthy 80-year-old female costs about 75 times more than for a similar 40-year-old.Although either donor may revoke the planned gift at the end of the year, the relative value of keeping the plan in place for one year is 75 times greater for the older donor.

The intention is the start, not the end.

The relative fluidity of charitable plans (especially as mortality approaches) underscores the importance of converting the revocable gift into an irrevocable gift where possible, especially for the relatively younger donor. Once the younger donor has made the bequest intention, moving him or her to an appropriate life income gift is particularly valuable. Why not ask, “Since you are already planning to leave a bequest gift, would you like to know how you can enjoy immediate benefits for this type of commitment?” That conversation can lead to many positive outcomes for the charity and the donor.

Notes

1. Available at www.sharpenet.com/resources/white-papers.

2. For different age groups over 50 and different 10-year starting points, the loss percentage ranged from 49 percent to 39 percent, with an overall average of 45 percent. Note that this survey tracks contemporaneous reports and does not ask current planned bequest donors to recall past dropping behavior.

3. U.S. data is more anecdotal, but this can clearly be seen in full reporting available in the U.K. in Charity Market Monitor by Cathy Pharoah.