Certain questions have tended to recur with regularity in our work with clients over the years. One we hear frequently involves concerns by development officers that donors will reduce or stop their current giving once they notify an organization of a bequest commitment, or make a gift in the form of a gift annuity or other deferred gift.

These concerns—especially on the part of those who may not be that familiar with the nuances of planned giving—are understandable and may at first seem valid.

Fortunately, experience shows that these worries are typically unfounded. Failure to understand the natural cycle that often culminates in a bequest or other planned gift can, however, lead to less-than-optimal results in both immediate and deferred gift development efforts.

Bequests and other gifts made as part of one’s long-term planning and current giving are not mutually exclusive. An examination and understanding based on research into donor behavior, donative intent and various points in the lifecycle of the donor explain why.

The bequest donor myth

We have often seen concerns raised by fundraisers whose professional experience stems from mass marketing techniques, such as direct mail and telemarketing, that people who notify charities of bequest commitments later in life all too often stop making current gifts shortly after notifying a charitable interest of their intentions.

That may sometimes be the case, but not for reasons one might initially assume. Some fundraisers believe most people don’t really want to give and must be convinced to do so through the use of peer pressure, premiums and other incentives. They may believe donors will stop giving if given the slightest excuse, and to them it may appear that seniors put charities in their wills and decide they have “done their part” and stop responding to future appeals—whether mass-based or in person.

Think for a moment about what that implies: How many parents decide to stop providing for children after including them in their will? Consider the beneficiaries most often named in a will: family members, close friends and charitable interests that have been elevated to the status of family member.

Thus, given the donative intent required to include one or more charitable beneficiaries in one’s will, why would a donor with that level of interest suddenly decide the charity is no longer worthy of support? These donors may stop giving shortly after they notify you of a bequest, but not for the reasons many might intuitively expect.

Lifecycle driven

In studies of the bequest programs of many educational, religious, health-related, social service, arts and other nonprofits over the years, we have observed a predictable pattern of bequest donors’ giving history.

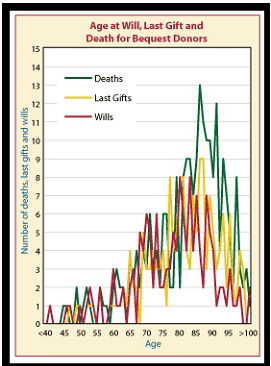

Based on the study of thousands of bequests actually received by a broad spectrum of organizations, we have determined that the average age at making the will that actually serves to leave funds for charitable purposes is 79, the average age at notification of that will is 81, the age at last gift is 82 and the average age at death is 85. The standard deviation from these averages is typically no more than two to three years. See a graphic illustration of this phenomenon for one organization at right.

Based on the study of thousands of bequests actually received by a broad spectrum of organizations, we have determined that the average age at making the will that actually serves to leave funds for charitable purposes is 79, the average age at notification of that will is 81, the age at last gift is 82 and the average age at death is 85. The standard deviation from these averages is typically no more than two to three years. See a graphic illustration of this phenomenon for one organization at right.

We could include dozens of charts for a variety of types of nonprofits and one would observe very little difference.

Don’t confuse cause and effect

Given that people tend to make their last will, notify the charity, make their last gift and pass away all within a relatively narrow time-frame, it should not be surprising that an uninformed observer might misconstrue cause and effect.

Simply put, donors are going to stop giving at some point; the issue is whether or not they include their charitable interests in their wills before they stop giving. In other words, the alternative is not a current gift versus a deferred gift, but in many cases a bequest or other deferred gift or no additional gifts at all.

Those who follow what their intuition seems to tell them may end up with surprising—and counterproductive—results. For example, imagine the impact of a policy that determines an organization can market bequests only to donors who have been lapsed for two years or more.

The theory underlying this approach is that you introduce donors to the idea of a bequest only after they have demonstrated they are no longer able to make current gifts. That approach, given the realities discussed above, is similar to applying fertilizer to a crop after the harvest has begun. The lack of impact on “yield” is completely predictable and should come as no surprise.

Giving may actually increase

Older donors who enter into gift annuities, charitable remainder trusts and similar deferred gift plans can be expected in many cases to actually increase their current giving.

The average age at the time of a gift annuity, according to the American Council on Gift Annuities (ACGA), is 78. (See acga-web.org.) For the remaining six or seven years of their life expectancy, these donors can in many cases be expected to maintain—or even increase—their current giving activity.

Why is that? Because donors give from disposable income. If an 80-year-old has $50,000 in certificates of deposit earning .05 percent or $250 per year, consider the economic impact on disposable (and donatable) income when that person funds a gift annuity using those low-yielding funds and begins to receive payments of 6.8 percent of the contributed amount, or $3,400, per year.

Those who have successful gift annuity programs often find that annuitants who used to give once or twice a year tend to give quarterly after receiving their checks—often giving more on an annual basis than they did before and giving longer than other donors their age.

A ring of truth

There are, however, situations where the concern that bequests and deferred gifts could stifle current giving may have merit.

Consider the case of a relatively young person, perhaps in his mid-60s with a life expectancy of 20 years or more, who is under pressure to make a large commitment to a funding initiative. In that case, he might make a significant bequest commitment or fund a gift annuity or other type of deferred gift as a way to participate. In those circumstances, we have, in some cases, seen a reduction or cessation of future giving.

A bequest is in many cases the final—or ultimate—expression of one’s donative intent. That being the case, care should be taken not to unwittingly “accelerate” that commitment too early in life. In the case of a 65-year-old bequest donor, what is the follow-up in the next campaign 10 years later?

If a donor is not able to make a significant outright gift at 65, what is the likelihood he will be capable of such a gift at age 75? Probably very little. Will the solution be to ask the donor to put you in his will again in the next campaign?

Be wary also of using charitable trusts and other tools that delay gifts until death too early in the donor’s life at the possible expense of future major gifts. A $100,000 gift completed today is “worth” $100,000. A $1 million bequest commitment from a 55-year-old with a 30-year life expectancy is worth $99,300 if discounted at the 8 percent long-term endowment return assumptions many report.

In effect, the two gifts are worth the same, but in the case of the bequest, it will be 30 years or more before the benefit is received and the funds to fulfill the bequest may or may not be in the estate at the time of death.

The donor, however, may naturally feel he has made a $1 million ultimate commitment to that charity and move on to other interests.

Bottom line

The bottom line is that a well-conceived and implemented planned gift development effort need not have a negative impact on current giving, whether “major” or “minor,” and may, in fact, serve to increase the amount a donor gives during lifetime.

Time-tested gift planning tools that are misapplied in the context of a donor’s lifecycle and institutional priorities may, however, lead to significant reductions in the total amount and overall value of a donor’s giving and other involvement.

One of the keys to success in today’s complex environment is to recognize that different types of gifts are naturally appropriate at different points in the donor’s natural lifecycle. The type of gift vehicle that is encouraged by charitable recipients should be informed by where a particular donor or group of donors happens to be in that lifecycle and be introduced at the appropriate time.