Even in the face of reported declines in overall fund raising, it should not be surprising to find that bequests remain a relatively reliable source of income and continue to represent a significant percentage of total funding for many organizations. In fact, in both good years and bad, many of the largest charitable gifts take the form of unexpected bequests, structured most often as all or a portion of what remains of an estate after first satisfying bequests to other heirs.

Charitable bequests remain relatively steady in challenging economic times for two primary reasons. First, actuarial realities continue regardless of economic conditions. As people pass away and their estates settle, bequests continue to be received and can represent the difference between a budget shortfall and a surplus in a given year.

Additionally, after extended periods of economic slowdown, history reveals that bequests gradually tend to assume greater importance and represent larger percentages of individual gift income. For example, Council for Aid to Education (CAE) reports reveal that bequests represented 27% of charitable giving from individuals in 1982, following one of the worst economic downturns in decades. Historically high levels of bequest income were also experienced during the period following the crash of 1987 and the recession of the early 1990s. Looking back even farther, 70% of the major gifts reported in 1932 came in the form of bequests.

Conversely, during times when the economy is booming and stock markets are at their peak, bequest income tends to represent a smaller percentage of overall giving.

The Chronicle of Philanthropy reports that 7 of the 10 largest gifts in 2008 were bequests. By comparison, there was not a single bequest listed among the top gifts in 2007, when stock markets were at record highs. In flush times, larger numbers of donors take advantage of increased stock and real estate values to make larger outright gifts.

Expect an echo effect

Even after the current economy rebounds, charities can expect to experience an “echo” effect, or a period in which bequests continue to be prevalent. Sharpe studies of thousands of actual estates received by many organizations of various types confirm that the average lag time between the making of the final will that leaves funds to charity and the death of the donor is approximately five years.

This five-year lag time between the making of the final will that includes a charitable bequest and its eventual receipt by a charity explains why it is so vital to continue emphasis on bequests during the worst of economic conditions. It is during an economic downturn that some donors, especially older and wealthier donors, may opt for bequests in lieu of larger outright gifts. In the past, this trend has been reflected in an increase in the percentage of bequests and other planned gifts in campaigns for various purposes during times of economic challenge. The receipt of bequests in the late 1930s, for example, helped lend momentum to the doubling of charitable giving during the recovery period from 1933 to 1941.

Age matters

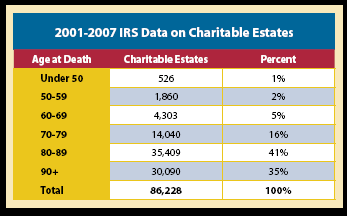

IRS data reveals that those who leave bequests, especially wealthier donors with taxable estates, tend to be relatively older persons. In fact, about 75% of such bequest donors pass away after the age of 80. Sharpe research reveals that the average age at the time of making a will that leaves a charitable bequest is the late seventies or early eighties, approximately five years before death.

Other reports also indicate the average lifespan of the wealthiest donors may be well above average. For example, The Chronicle of Philanthropy recently reported that bequest donors among the ranks of the top 50 donors overall in 2009 died at an average age of 92. Only two out of eleven died before reaching the age of 90—one at 85 and one at 62.

Missing a window of opportunity?

Some fundraisers believe they should focus marketing efforts on younger donors because donors 70 and older have “already made up their minds” and “won’t change their wills.” However, many of those with years of experience in the field know that nothing could be farther from the truth or have the potential to do more harm than basing the core of marketing efforts on these assumptions.

It is obviously true that donors to some organizations will include those charities in early wills when they are first married or have children. Others may include charitable interests in wills completed in their middle years. For these reasons, it is important to make periodic efforts to be included in the wills of all interested persons to help ensure a continued flow of bequest income some 20 to 50 years from now.

In times of economic stress, however, it is more important than ever to carefully allocate limited resources and make every effort to discover and work with the donors who are likely to be making their final estate plans.

Keep in mind also that many types of organizations don’t even acquire bequest donors until relatively late in life. Recently a nationally known organization studied all bequest files for a given year to determine the age at which actual bequest donors made their first gift to the organization. The 80 bequest files revealed that bequest donors made their first gifts at an average of 75, which was also the median age. Most of the donors did not make the final will leaving bequests until they had been on file for a number of years. For this reason, it is important to understand who your bequest donors really are!

Numbers up, value down?

Despite the surge of bequests during periods of economic distress, management must understand that while the number of bequests may increase, their average size may be depressed somewhat, especially during the current period of downturn.

Recall that the largest bequests often come from residuary estates. Imagine a donor with an estate of $750,000 executes a final will that provides for distributions of $100,000 each to five nieces and nephews. After these distributions, the will stipulates that the remainder be split among seven charities. If the donor passes away while the estate is valued at $750,000, the nieces and nephews would receive $500,000 “off the top” of the estate with the remaining $250,000 divided among the charities. Each charity would receive a little less than $36,000, which is a fairly typical charitable bequest.

Now suppose that the donor had 20% of his or her assets ($150,000) invested in a Dow index fund that fell 30% prior to the donor’s death. The original $150,000 amount would be reduced to $105,000. The entire drop in value ($45,000) would be absorbed by the residuary estate. The residue would then amount to only $205,000—not $250,000—and each charity’s share would drop by 18% to just over $29,000. Even in estates that don’t include securities, similar effects can be felt as a result of declines in real estate values.

Declines in asset values thus help explain why the amount of funds received from estates planned in the past may actually decline even when the number of bequests increases.

Part of the solution to the downward pressure described above is to take steps to ensure that an organization will stay in as many estates as possible. Charities that are maintaining strong relationships with donors in their final years on file, especially those who have previously revealed the presence of a bequest in their estate, will find they may be able to counter declines in average-size bequests.

For example, imagine if after the final will was completed in the case above, the donor decided to remove two of the seven charities because they had not been in touch since they sent a notification of their intention, while the other five had done an excellent job. In that case the smaller residue would be split five ways instead of seven and each of the remaining charities would receive $41,000, more than they would have received prior to the economic downturn and 40% more than the $29,000 that would otherwise be expected after the market slump.

This “math” explains why organizations with strong and effective bequest awareness and stewardship programs may see less impact from periods of economic distress than others.

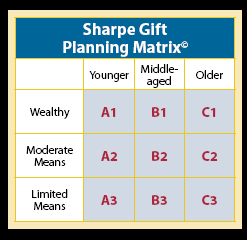

Another way to counter drops in bequest income due to declines in average size is to encourage as many “new” bequests as possible from age-appropriate donors or constituents. This may best be accomplished by using the Sharpe Gift Planning Matrix© to focus your marketing budget and staff time on the oldest portion of your file that is likely to produce tangible bequest maturities in the relative near term.

The next few years will be critical ones for charitable entities that wish to remain viable in light of an aging population and what may be an extended period of slow economic growth. Fund development executives need to understand where bequests come from and take the steps necessary to influence larger numbers of donors who are in the process of making their final estate plans.

Note: This article is excerpted from Sharpe’s popular seminar “Introduction to Planned Giving.” See page 3 for more information about Sharpe seminars.