When Congress first acted to lower the estate tax over time through provisions included in the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act (EGTRRA) of 2001, the year 2010 seemed far away—certainly allowing more than enough time for Congress to agree to a long-term estate tax solution that would balance the concerns of various parties.

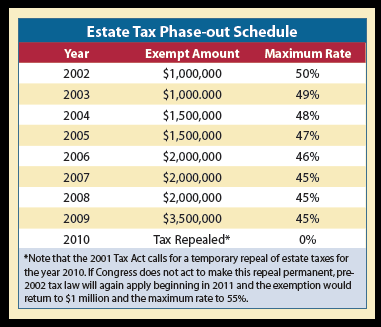

After a gradual reduction from relatively high 2001 tax rates, the federal estate tax rate was slated to be repealed completely in 2010—acting as a sort of self-imposed deadline for Congress to act—before rebounding in 2011 to a 55% top tax rate and a $1 million exemption amount.*

After almost 100 years of estate taxes in America, heirs in 2010 would be allowed to receive their inheritances without a portion paid to the federal government—but only if Congress failed to take action to enact new legislation. Most experts believed the looming threat of an estate tax repeal—and the ensuing loss of revenue during a period of growing deficits—would compel Congress to act. Even at 2009 estate tax rates, for instance, federal estate tax revenue approached an estimated $14 billion, income that could be lost under current law in 2010.

Yet the deadline of December 31, 2009, came and went with no action by Congress. Now estate and financial planners are left trying to advise clients on the best ways to navigate a maddeningly uncertain income and estate tax planning landscape.

What Congress will do

No one knows when or how Congress will act regarding the estate tax, though speculation abounds. Lawmakers have proposed an assortment of solutions, including a “prepaid” tax similar to a Roth IRA, a retroactive reinstatement of 2009 estate tax rates and exemptions to affect all 2010 estates, an all-out repeal of estate, income, and gift taxes in favor of a national sales tax, and varying exclusion and tax rate ratios. Any proposal is sure to meet its share of opponents.

Many experts believe that legislators will ultimately decide to adopt 2009 estate tax rates moving forward. Indeed, the House voted at the end of last year to extend 2009’s estate tax rates and exemption amounts, but the Senate failed to follow suit. President Obama’s 2011 budget also calls for continuation of the 2009 tax levels featuring a 45% top tax rate and $3.5 million exclusion amount. A popular Senate proposal, however, would set a $5 million exemption amount with a top tax rate of 35%.

And as the year drags on, any retroactive change will also likely face legal opposition from heirs, such as those who stand to inherit the $9 billion estate left when Texas gas pipeline tycoon Dan Duncan died in March. It could be years before federal courts decide the tax ramifications for those who die this year. As of now, one solution for dealing with 2010 estates that seems to be gaining momentum is to allow executors to choose to file under either 2009 or 2010 rules.

Surprisingly, some estates would be better off with 2009 tax rates. In past years, heirs were allowed to “step up” the cost basis of appreciated property to the value at which the property was inherited to avoid having to pay both capital gains and estate tax on inherited assets. As part of the compromise reached in 2001, in an effort to counterbalance the estate tax repeal, the capital gains step-up provision was limited to the first $1.3 million in assets with more generous provisions for spouses. As a result, a certain number of estates with highly appreciated assets would ultimately owe more taxes without the estate tax than with it.

As commentators predicted in 2001, if the elimination of stepped-up basis were to become permanent, many middle-aged heirs might find themselves suddenly owning large amounts of appreciated, low-yielding assets that could be ideal for funding charitable remainder trusts.

What the wealthy will do

How the wealthy are handling their estate planning decisions is also a matter of some speculation. The uncertainty of both how and when the estate tax will change has led many to take a wait-and-see approach with their estate planning for fear of incurring unnecessary and perhaps repetitive legal costs.

Yet there are a number of reasons the wealthy may need to update their plans this year. Given the gradual change in estate tax exclusion amounts, some wills may include outdated provisions such as a bypass trust or other measures originally designed to minimize the impact of an estate tax. With no estate tax in place this year, such language could have unintended consequences for a spouse or other heirs.

The wealthy should also take the time to make note of the cost basis of property that has appreciated over their lifetime. Under current law, heirs must be able to show the cost basis; otherwise, the government assumes a cost basis of $0, leading to heavy capital gains taxes. In the case of certain assets, it may be very difficult to discover the original cost basis for something purchased many years before.

Impact on charitable giving?

It is difficult to gauge the impact that estate tax uncertainty is having on charitable giving. No one can say how many donors have postponed establishing a charitable trust or drafting a will with a charitable bequest until after Congress takes definitive action. The concurrence of the lapse in the estate tax with the recent economic downturn makes such speculation even more difficult.

Many charities are finding that distributions from the estates of those who have recently passed away are being delayed. Some executors are hesitant to settle an estate with the future of the estate tax still uncertain. Others may be trying to wait for a more complete rebound of real estate and stock prices before selling assets included in the estate. In other cases, a will may provide for charitable bequests only of the amount that would otherwise be subject to estate tax. Under the current situation, it may not be possible to determine that amount for some time to come.

Regardless, the result for nonprofits is, for many, a reduction and/or delay in the amount of income that would normally be received from bequests.

Some assume that without the estate tax, donors will lose the incentive to make charitable bequests. Others believe that donors may give more since the amount they can leave to their other heirs will increase when taxes are lower. No matter what the current estate tax level may be, it is important to remember that giving to charity is never without cost, and the cost of a charitable gift to the donor is the same regardless of which institution is chosen to receive the gift. The ultimate motivator for any donor is usually tied much more closely to emotion than taxation.

For these reasons, it is crucial for nonprofits to maintain regular and meaningful contact with donors during this time. Remember that the majority of bequests have always come from non-taxable estates prior to this year’s confusion and the vast majority of donors are unaffected as their estates were already under the tax threshold prior to the repeal.

When Congress finally does take action, there is likely to be a flood of estate planning activity. The wealthy will be rushing to their financial planners to get their estate plans in order, and advisors are sure to ask them about their charitable intentions. Nonprofits that have maintained contact with donors will be certain to be top of mind when many older affluent donors may be making the final revisions to their plans.

For more on the current uncertainty and its effect on planning, see The Wall Street Journal’s July 10, 2010, article “Too Rich to Live,” authored by Laura Saunders and Mary Pilon.

*Note the exemption was $675,000 in 2001 but was scheduled to be increased to $1 million by 2006 under the law of that time, so when the law reverts to 2001 amounts, the exemption will be $1 million per person.