By Professor Christopher P. Woehrle, J.D., LL.M

A charitable remainder trust permits annuitization of the full value of the appreciated asset without the donor incurring a capital gains tax. For the charitably inclined, the technique facilitates diversification of a portfolio and potential improvement of cash flow. The Biden Administration’s General Explanations of Fiscal Year 2022 Revenue Proposals would change this long established regime.

The Administration proposes to treat transfers of appreciated property by gift or on death as realization events. For years, the estate tax has been described as taxation without respiration. The Administration would now impose recognition without any actual realization. The amount taxed would be the difference between the fair market value of the assets on the date of gift, or death, and the donor’s basis in the asset.

The capital gains tax at death would be deductible in the calculation of the estate tax, though it would not be a credit.

Although outright lifetime gifts to charity would not be taxable, transfers to a split-interest trust (a charitable lead trust or a charitable remainder trust) would be taxable except to the extent of the value of the charity’s interest.* Specifically, the exclusion would be allowed for the charity’s share of the gain based on its share of the value as determined for gift or estate tax purposes; i.e. the present value of the charitable remainder interest.

This treatment would come closer to mirroring the taxation of funding a gift annuity with appreciated property. A portion of the gain is deemed gifted to charity and the balance of the gain is recognized over the lifetime of the donor or immediately if for the lifetime of someone other than the donor.

The proposal provides several exclusions including $1 million per person as well as an election for certain transfers of illiquid assets to be taxed over 15 years. Transfer between spouses would not generate tax until the spousal donee sells or dies.

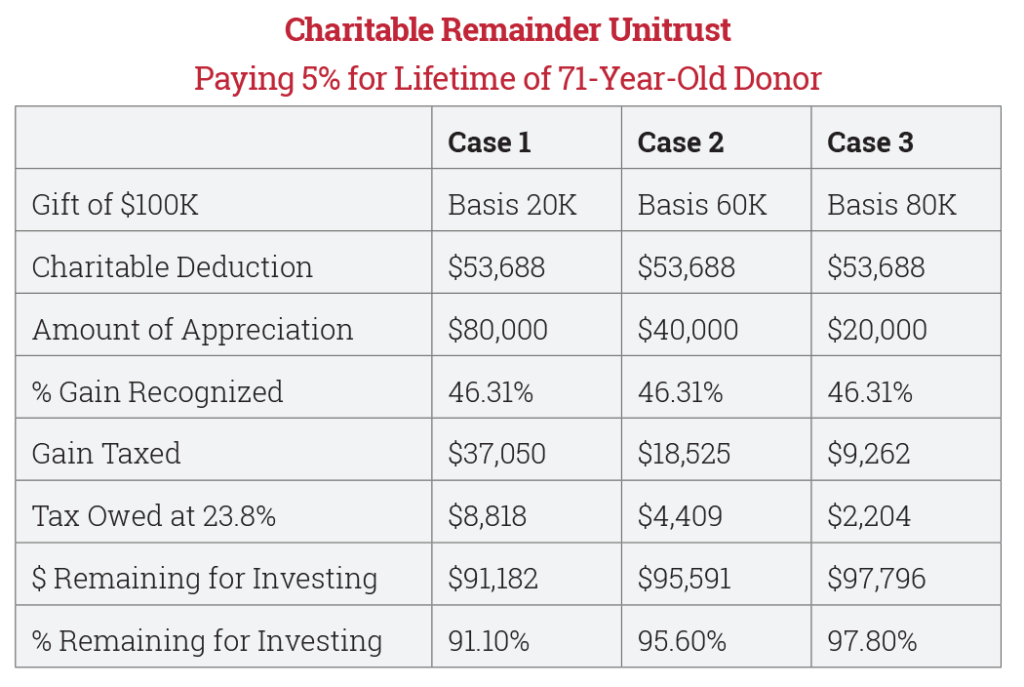

Let’s examine how the economics of split-interest charitable giving would be altered (see chart). Assume a 71-year-old donor will fund a unitrust with a 5% payout rate. She is deciding among three different tranches of stock with the amount of appreciation being 80%, 40% and 20%. Although the charitable deduction for the remainder will be $53,688 per $100,000 gifted, the amount of tax triggered differs. The more appreciated the asset, the greater the reduction in the amount available to be annuitized. Even in Case 1 with 80% of the value being appreciation, the reduction from taxes is less than 10%.

While it may be premature to predict whether or not this provision will be enacted in any future revenue bill, it merits monitoring. Should this provision be enacted, it illustrates how provisions aimed at the wealthiest can impact more than the intended taxpayers. ■

*https://home.treasury.gov/system/files/131/General-Explanations-FY2022.pdf. p. 62, which reads: “A transfer would be defined under the gift and estate tax provisions and would be valued using the methodologies used for gift or estate tax purposes. However, for purposes of the imposition of this tax on appreciated assets, the following would apply. First, a transferred partial interest would be its proportional share of the fair market value of the entire property.”

Christopher P. Woehrle is professor and chair of the tax & estate planning department at the College for Financial Planning in Centennial, Colorado. As one of Sharpe Group’s technical advisors, Chris is a frequent contributor to Sharpe Insights and authors Sharpe Group blogs.

Christopher P. Woehrle is professor and chair of the tax & estate planning department at the College for Financial Planning in Centennial, Colorado. As one of Sharpe Group’s technical advisors, Chris is a frequent contributor to Sharpe Insights and authors Sharpe Group blogs.