In recent years, there has been a growing interest in the role of charitable bequests in the overall fund-raising mix, and rightly so. Charitable bequests provide more philanthropic support than many suspect. In fact, more donated funds each year come from bequests by individuals than from gifts by corporations, and bequests have accounted for 20% to 25% of all gifts from individuals to higher education over the past 25 years.

As a result, the number of studies and surveys about charitable estates has been steadily increasing. Depending on the source, the research findings can be helpful, intriguing, contradictory, or downright misleading (see the May 2009 issue of Give & Take to explore the difference between intention and behavior in marketing studies).

For example, consider the 2008 Bank of America study of philanthropy among high net worth individuals. According to the survey, over half of wealthy individuals (56%) claim to have already included a charitable provision in their will. An additional 37% of survey respondents indicate that they would consider establishing a charitable provision in their will at some point in the next three years, bringing the total of eventual bequest donors to 93% of all wealthy Americans.

If these survey results prove true and 93% of high net worth individuals do indeed include bequests to charity within three years, those charged with raising funds should pat themselves on the back for a job well done.

Unfortunately, a number of other studies have come to very different conclusions. Some have found that as few as 5% to 8% of the general adult population actually include charitable provisions in their wills or other estate plans. Other reports offer conflicting data on the age and gender of bequest donors, making it difficult for fundraisers to create a useful profile.

Looking for the truth

Many fund-raising executives are struggling to make sense of these findings as they try to determine the best use of limited staff and budget resources. Some are in danger of targeting the wrong audience at a time when it’s especially important to get the best return on their investment of time, money, and other resources.

During the next few years, planned gifts that provide benefits to charity in the near term will be especially important—and this includes bequest provisions that may mature in three to four years instead of three to four decades. But how can fundraisers find the truth about charitable bequests?

According to the IRS

When faced with difficult fund-raising decisions such as how to market bequests, it is best to rely on historical data rather than survey responses, which can be skewed in various ways. Probably the most extensive and accurate source of data on charitable bequests that have actually matured can be found in federal estate tax returns filed each year with the Internal Revenue Service.

A wealth of behavioral and other data can be gleaned from carefully studying information based on federal estate tax returns each year. This information can then be used to help fund-raising executives, donors, and advisors make appropriate decisions concerning charitable estate planning.

Let’s review some of the findings of the IRS researchers, compiled from actual tax returns and made available through various studies and reports found on the IRS Web site, www.irs.gov.

What percentage of the affluent actually include charities in their estate plans?

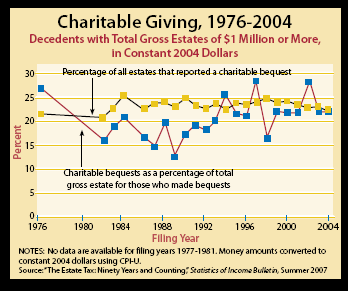

The IRS provides a great deal of data that is helpful in identifying current and historical trends regarding gifts through estates. For instance, the chart below examines charitable giving over the almost 30-year span between 1976 and 2004. During this period, despite enormous fluctuations in the economy, the percentage of wealthy decedents who made a charitable bequest remained fairly constant at 20% to 25%.

Compare this figure to the Bank of America study mentioned earlier. While 56% of respondents report having made a charitable bequest and 37% more say they would consider doing so within three years, history tells us instead that a much smaller percentage of wealthy decedents will actually follow through with a charitable provision in their will at the time of death.

There are at least four explanations for this disconnect. First, the 700 respondents from the 20,000 surveys mailed may have been inordinately skewed toward bequest donors because of the charitable nature of the survey. This is born out by the fact that some 50% of respondents said they serve on boards. Second, the respondents could have simply answered the question untruthfully, which is unlikely. Third, the bequests could be contingent on a spouse and/or others predeceasing the respondent or other factors occurring before the bequest could actually take place. Fourth, the findings could be currently valid, yet many of the respondents may remove charities in their later wills when the competing needs of family may preclude the bequest. No one knows the true explanation, but we do know that over the years the number of wealthy persons who include bequests in their plans is much closer to 20% to 25% than 50% to 90% or more.

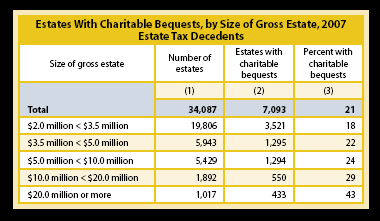

A further examination of individual estate tax returns in 2007 (see chart below) indicates that the probability of including a charitable provision rises as the size of the estate increases and is highest among estates over $20 million. For relatively smaller estates, the figure drops slightly below 20%.

Does age matter?

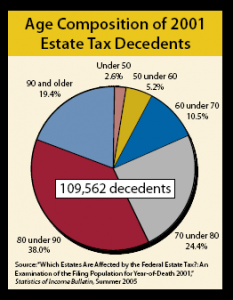

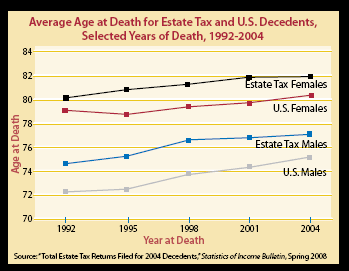

Based on information from large numbers of decedent estates, the age of the donor seems to be the most critical factor affecting what is actually coming out of the planned giving pipeline. For instance, almost 60% of all decedents who were subject to the estate tax in 2001 were over the age of 80. In 2004, females subject to the estate tax averaged 82 years at death, while their male counterparts lived to an average age of 77.2 years.

It is worth noting in the chart below both that wealthy Americans tend to live longer than other Americans and that Americans of all ages are living longer than they have in the past.

The average age of American decedents may explain why some programs that are counting all new planned giving expectancies—regardless of the age of the donor—as actual production are realizing only a trickle of maturities each year. In times like these, directors of such programs may experience increased scrutiny from senior management and the board.

Other factors to consider

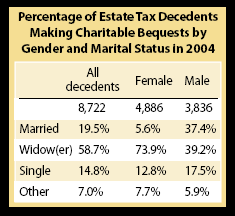

In addition to age and wealth, the IRS tax return data and studies reveal a variety of other factors important to consider, including gender and marital status. For instance, women are traditionally more likely to make charitable bequests than men. This fact has been attributed to the fact that women live longer than their male counterparts. At death, many men are married and choose to provide for their surviving spouse. Women are for the most part widowed or single at death; their estate plan, therefore, is more likely to include charitable distributions.

The presence of children and/or grandchildren is also a factor that should be considered and will affect both the likelihood and the amount of a charitable bequest. Although single (never married) decedents constitute only 7.1% of all 2004 estate tax decedents, they represent 14.8% of those leaving a charitable bequest. Conversely, 46% of all estate tax decedents in 2004 were married at death, yet only 19.5% of those making charitable bequests were married.

Stay informed

Given the conflicting nature of the reports, studies, and data available, it is more important than ever to be an informed consumer of this information and to make decisions based on institutional priorities and objectives.

Consider your own recent planned maturities. Just take the last ten maturities and examine the decedents’ age, gender, marital status, gift history, and other factors. Pay special attention not only to the age of persons who left bequests at death; also examine the age when they executed the will that left the funds. If your program is like every program studied by Sharpe consultants over the years, you will find that the vast majority of your bequest maturities are coming from persons who made their final will after the age of 70.

If your program does not have adequate records, consider an alternative approach. Simply pick up today’s newspaper and turn to the obituary page. Take the time to carefully study its contents for clues about the people who have died in your own community. Compare their age at death with civic activities and other clues such as marital status and surviving children.

After considering the information you learn by reading the obituaries, circle the 20% that you personally suspect may have included a charitable bequest in their estate plans. Choosing likely donors is easier than you think, and you may have increased confidence in your planned giving IQ after taking this test!

Once you have identified an accurate profile of planned giving donors, you can make a rational decision about deploying staff and budget in a fashion that will provide optimum results for both the near and long term.