What if you have just been assigned the responsibility for beginning or enhancing your organization’s “planned giving” program? In order to succeed in this endeavor, we have found that it can first be a good idea to make sure you fully understand what is meant by the term “planned gift.”

The Sharpe Group first began referring to the process of incorporating larger gifts as part of a donor’s broader estate and financial planning as “planned giving” in the wake of the 1969 Tax Reform Act, which codified many types of gift vehicles that had prior to that time been known as “deferred gifts.”

Nearly 20 years later in the March 1988 edition of Give & Take, we first defined a planned gift as follows: “A planned gift is any gift of any kind for any amount given for any purpose—operations, capital expansion, or endowment—whether given currently or deferred if the assistance of a professional staff person, qualified volunteer, or the donor’s advisors is necessary to complete the gift. In addition, it includes any gift which is carefully considered by a donor in light of estate and financial plans.” Give & Take, Vol. 20, No. 4, March 1988

This definition of a planned gift was and still is based on the premise that every gift has five elements: who makes the gift, why they make it, what they give, when the gift is completed, and finally, how the gift is structured.

Over the years, we have observed that in some organizations, one group of fundraisers will concentrate on the “who” and the “why” of gifts. That group typically comprises those responsible for direct mail, annual giving, major gifts, and/or a capital campaign. At the same time, a separate group is then charged primarily with overseeing the “what,” “when,” and “how” of gifts, regardless of size. Those responsibilities are sometimes referred to as the “planned giving” or “gift planning” function.

The programs that will succeed in the future will be the ones that successfully integrate the gift planning process with related elements of their other fund development efforts. Programs that persist in pursuing “planned giving” or “major giving” in what are sometimes referred to as “silos”— separate from each other and/or other funding efforts—will find it difficult to succeed in an increasingly competitive environment.

Appealing to the donor

Over 15 years ago, in the midst of the recession of the early 1990s, we first introduced a conceptual framework that approaches fund raising primarily from the perspective of the age and wealth of donors, while also incorporating the size of gifts, their timing, and the various needs of the charitable entity for current, capital, and endowment funding.

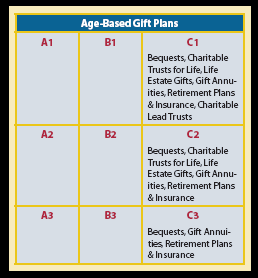

The Sharpe Gift Planning Matrix© starts with the premise that all donors fall into certain age ranges as they proceed through their natural donor life cycle, for our purposes three broad groups—those under age 50, those age 50 to 70, and those over the age of 70.

The exact age ranges most appropriate for your organization will be determined by a number of factors. For example, one organization may find it useful to target a slightly younger audience with a mid range of 45 to 65, while another may wish to reach an older group with a mid range from 55 to 75. Subtle alterations in the matrix concept allow organizations to personalize this approach for greater effectiveness.

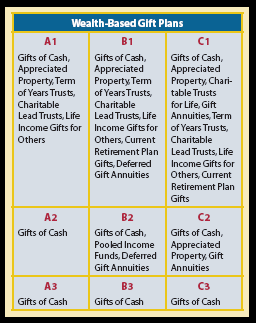

Every donor also fits into a category of wealth we refer to as high wealth, average wealth, and those of limited means. The wealth amounts are also relative and will vary by type of institution.

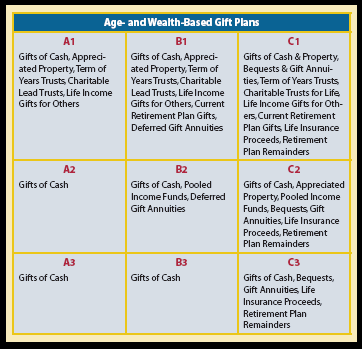

By combining these two categories of age and wealth, every donor falls into one of the nine boxes depicted at right.

In today’s environment, it is more important than ever to approach donors in the various categories in different ways. For example, an approach that may succeed with an A1 donor may be inappropriate for someone in the C3 box, and vice versa. Everything from mission focus, to method of communication, to graphic elements in published materials should ideally be designed to appeal to those in the particular target audience. This approach allows you to tailor the message and the medium depending on the generation or cohort group selected.

Not surprisingly, the gift planning tools at our disposal also vary in their applicability depending on age and wealth. While there is room for slight differences in the composition of the group that each plan applies to, some gift planning tools such as gift annuities are primarily applicable to those in the C category. For example, American Council on Gift Annuities (ACGA) studies have shown that the average age of new gift annuitants is 78, with relatively few persons under the age of 70 utilizing this plan. As lower interest rates have resulted in reduced payment rates and smaller charitable deductions for younger persons, this has become even more the case.

Likewise, the operative wills that name charitable recipients are normally executed by persons in their late seventies to early eighties. While surveys of younger people will always show that many “intend” to one day include a charity in their estate plans, IRS data published year after year and other studies of actual behavior indicate that people who die before they reach the age of 65 or 70 rarely leave bequests to charity. When they do so, their bequests comprise relatively small percentages of the estate as most persons who die in that age range are married and leave everything to a surviving spouse under the unlimited marital deduction if they are wealthy and out of necessity if they are not.

While other studies have indicated some may first include charities in their wills as early as their twenties, the only will that ultimately results in a charitable disposition is the final will. Therefore, to influence bequests in the near term, it is important to influence the behavior of persons in the older age ranges. Keep in mind when planning budget expenditures that the average 65-year-old has a life expectancy of 20 years or longer, depending on the mortality table you choose. In the case of a 55-year-old, the life expectancy is right at 30 years, while a 45-year-old can expect to live for almost 40 years.

Additionally, tax-free IRA gifts currently apply only to those over 70½ who are well off financially.

As bequests and gift annuities, charitable remainder trusts for life, and certain other plans are primarily age-oriented in their appeal, they are naturally more appropriate for the oldest donors (C1, C2, C3).

On the other hand, another category of planning vehicles primarily appeals to donors based on their wealth rather than their age. Gifts of appreciated assets, charitable remainder trusts for a term of years, charitable lead trusts, gift annuities benefiting older loved ones, and other tools tend to be more attractive to those across the top of the matrix.

All of the vehicles we commonly refer to as “planned gifts” find a home in one or more of the matrix boxes, depending on the age and/or wealth of the donor.

Note that some planning tools, such as IRA rollovers, appear only in the C1 box because they are restricted to persons over the age of 70 because of  legal restrictions and economic circumstances that make such gifts possible. Reports from the Partnership for Philanthropic Planning (formerly NCPG), for example, indicate that over 90% of IRA rollover gift income has come from distributions of $5,000 or more.

legal restrictions and economic circumstances that make such gifts possible. Reports from the Partnership for Philanthropic Planning (formerly NCPG), for example, indicate that over 90% of IRA rollover gift income has come from distributions of $5,000 or more.

This brings us to the most conspicuous area of overlap between what many consider to be “planned gift” and “major gift” prospects.

What if one department is handling a segment of donors because they are wealthy and are “major donors” while another department is interested in the same group because they are older and are thus considered “planned giving” donors? In this case, a growing problem may loom ahead as major donors are increasingly found among the ranks of older, wealthy individuals who reside in the C1 category, where the greatest overlap between planned and major gifts tends to occur.

Matrix-based marketing

Instead of looking at the matrix from the outside, imagine you are a donor looking out at your organization and its fund development efforts from inside various boxes in the matrix. What does a person in the A1 box see? Is it different from what a person in the C3 box sees? Do they perceive your organization differently depending on their level of wealth and giving capacity and where they are in their life cycle? Should you communicate the same messages to them in the same way?

For example, a younger person of means in the A1 box may be invited to events, be cultivated for larger gifts, or be a prime candidate for an outright campaign gift. Much of your communication with him or her will be in person or via e-mail and visits to your Web site. That person’s grandmother in the C2 or C3 box may, on the other hand, be in her final years as a donor, be reducing the amount she gives currently, and be contemplating a gift annuity or considering the provisions of her final will. In that case, there is at least a 50/50 probability that she does not own a computer and has never been and will never be online. She relies primarily on the printed word for information and may have a VCR (not a DVD player) that has been blinking 12:00 for 20 years.

Our means of communication must therefore vary depending on age, wealth, education level, and other factors. Much has been said about the need to utilize the Internet in planned gift marketing (see the July 2009 issue of Give & Take). It is indeed important to make information about charitable gift planning available online for computer-savvy donors of all ages.

Untangling the web

That being said, the majority of persons who are online are still under the age of 70. Think for a moment about what that means for those who are charged with influencing gifts from persons who are primarily over the age of 70.

As noted earlier, those responsible for marketing primarily in the right column of the matrix should keep in mind that the average age of persons who enter into charitable gift annuities is 78 and the median age is often closer to 80. People generally make final decisions about which charities will receive bequests from their estates at about the same age.

It is important to explore all viable ways to reach out to older donors, but those in their late seventies and older are at present generally not proficient with Web technology. Research shows that the seniors who are online are most likely to limit their activity to e-mail and research into financial and health-related subjects. This bodes well for the future of web-based communications with this group. Keep in mind, though, that even as older donors become increasingly computer literate, physical limitations based on age-related degradation of vision, attention span, short-term memory, and manual dexterity will ultimately limit the practical use of advanced technology for many.

Despite these limitations, as Boomers and other younger donors move into their later years, those in their seventies and older will steadily form more of an online presence. In the meantime, Web-based gift planning communications should primarily target the important segments of the younger, wealthier donors found in A1, B1, and C1 across the top of the matrix.

Practical matters

When using e-mail blasts and similar approaches with this younger group, remember that, with one or two keystrokes, the donor may send all future e-mail from your organization to a junk file never to be seen (or opened) again.

Also, keep in mind that most persons in their fifties and sixties are still working and are besieged by e-mail from all directions. The rapid proliferation of handheld devices used to screen and respond to e-mail among younger persons may mean that fewer e-mail recipients can easily access embedded links to Web sites. Some have suggested that the most savvy planned gift marketers might even want to consider skipping e-mail and moving to text messaging and Twitter for younger donors on the go.

E-mail attachments can save time and money, but by sending an “e-brochure” we are not only assuming the donor knows how to open the attachment but also are asking an elderly person who may or may not have a functional printer to use a significant portion of an ink cartridge to print it out. Make a point to consider these issues when designing materials intended to be printed at home.

Those who decide to rely totally on Web-based marketing for bequests and other planned gifts that require older donors to pass away should not expect to influence very many gifts that will be received in the next 20 years. They may, however, find support among their colleagues who work in other “silos” and still rely heavily on mail and other print-based fund raising as those fundraisers may welcome the departure of the planned giving program from the mail cycle.

On the other hand, others in the development office may be afraid that too much e-mail communication with younger donors on the subject of planned gifts that are more appropriate for older persons could divert attention away from their efforts to encourage outright gifts to annual funds, capital campaigns, and other initiatives aimed at the younger segment.

Mixing media

We believe the solution is to carefully mix your media. Across the top of the matrix, the use of the Internet combined with traditional mail and other communications with younger people will be increasingly effective. Make information available about gift planning ideas that are appropriate for relatively younger persons. In the C1 box, most of the proactive communication will continue to be controlled by those responsible for major gifts, campaigns, and other initiatives aimed at the wealthy of all ages.

In the C2 and C3 boxes, where most age-sensitive planned gifts originate, information should be readily available online for those donors who prefer this method of communication, while regular mail, articles, and other more traditional means of communication will in the near term continue to be the mainstay.

So, e-marketing is neither an ill-advised fad nor a marketing panacea, but it does offer unique opportunities for fundraisers to reach out to donors if used in an appropriate and thoughtful manner. Web-based planned giving may in the final analysis prove to be more of a fulfillment and gift completion aid than just a traditional “lead development” tool.

Do not succumb to the temptation to rely on the marketing concept du jour. Over the past 25 years we have seen various methods of marketing proclaimed as the “be all and end all.” This includes segmented direct mail and 800 numbers in the 1970s, planned giving videos in the 1980s, computer-aided research and list enhancement in the 1990s, telemarketing for bequests in the 1990s, seminars for donors on a regular five- to seven-year cycle, seminars for advisors in the 1980s and 1990s, broadcast faxes in the 1990s, and many others. All have found a place in planned gift marketing, and so will e-marketing over time. None are exclusive, and Web-based communication will not be either.

The key is to be flexible. If donors tell you they want to correspond by e-mail, do that. If they prefer traditional mail as evidenced by their behavior in their other interactions with you, take that cue as well. If they want to invite you to discuss a gift with them in person as a guest on their private jet, then be prepared to go!

Those who succeed in fund raising in coming years will do so only by carefully considering their methods of communication and outreach in light of the age and wealth of their donors, the nature of their mission, and many other factors. For those who are able to shape their message differently for donors at various stages of their personal and economic life cycles, a bright future lies ahead.

This article is excerpted from material presented in the popular Sharpe seminar “Integrating Major and Planned Gifts.” For more about Sharpe training opportunities, visit www.sharpenet.com/seminars.