Recent IRS reports indicate tax law changes may have distorted giving for 2017 and 2018.

In June 2018, Giving USA announced total giving of $410 billion for 2017, a new record and the first time in history Americans gave in excess of $400 billion. Outpacing the annual growth of the economy, wages and inflation, individual giving was pegged at $287 billion for the year, an increase of 5.2% over the previous record year of 2016. This was welcome news for America’s philanthropic community.

Even better news?

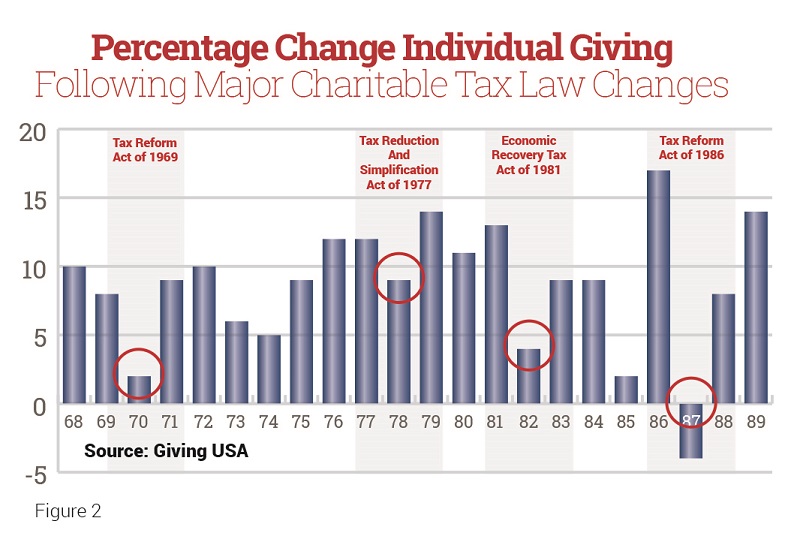

Historically, the amounts deducted on tax returns closely track the total amount of individual giving. Figure 1 shows the relationship over 21 years between the final amounts of deductions reported by the IRS and the final amounts for those years subsequently reported by Giving USA. Between 1996 and 2016, IRS deductions amounted to 82%, on average, of reported individual gift totals.

Historically, the amounts deducted on tax returns closely track the total amount of individual giving. Figure 1 shows the relationship over 21 years between the final amounts of deductions reported by the IRS and the final amounts for those years subsequently reported by Giving USA. Between 1996 and 2016, IRS deductions amounted to 82%, on average, of reported individual gift totals.

In March of this year, the IRS released preliminary estimates of charitable gifts deducted by donors on 2017 income tax returns. This report revealed the amount of charitable gifts deducted for that year increased over preliminary 2016 estimates by 11%, more than twice the individual giving growth rate initially estimated for 2017 by Giving USA in its June 2018 report. If these numbers are confirmed in final deduction figures from the IRS (expected this summer), 2017 may become only the second year since 2004 to see double-digit growth in individual giving.

How to explain the growth differential

The 2018 Giving USA Report will be released in June of this year, and it remains to be seen the change in individual giving that will be reported by this leading benchmark for giving and how initial 2017 estimates may or may not be revised.

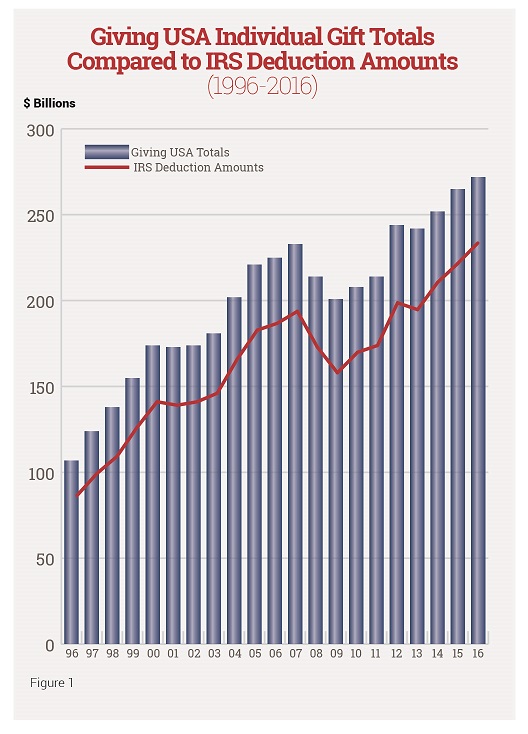

Is it possible giving could have actually fallen last year from record 2017 levels due to tax-related timing issues? History reveals that individual giving does sometimes decline in years following major revisions in federal tax laws.

This is especially true when the revisions reduce the benefit of charitable gifts in subsequent years for some donors, especially those making gifts of relatively larger amounts. This phenomenon was most recently observed in 1987. Giving in that year actually experienced negative growth in the wake of 1986 tax legislation that dramatically lowered tax rates (resulting in less tax savings for gifts made by some donors in 1987 than for gifts made in 1986). Figure 2 (top of Page 7) reveals the same reduction and later rebound also occurred following the 1969, 1977, 1981 and 1986 tax reform acts.

Rollercoaster effect

Fundraisers and policymakers need to understand why these declines and rebounds may naturally occur in the wake of certain types of changes in tax laws. The answer may not be as simple as we think. It’s easy to assume that giving drops after tax law changes because the changes reduce some of the benefits of charitable giving. That may be true to some extent, but there may be a more subtle explanation that seems to be borne out by history.

Borrowing from Peter…

Sharpe Group has observed and reported on each of the major tax acts over the past 56 years. Each time the law was changed to limit charitable deductions the following year and/or lowered tax rates in ways that would reduce the value of tax deductions in the future, donors have been urged by charities and tax advisors (and rightly so) to consider increasing their donations in the year preceding the effective dates of the new laws.

Whether referred to as “bunching,” “accelerating” or another term, this advice was extended in 1969, 1977, 1981 and 1986. Not surprisingly, many donors heeded this advice, at least partially causing the rate of increase in giving to hit record or near-record levels for those years. The same advice was widely disseminated in the fall of 2017 following the enactment of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 and may have also boosted growth along with investment market gains and other factors.

In the years immediately following the tax law changes, there was an understandable decline in giving presumably caused to some extent by donors accelerating gifts that would have been made in that year to the prior year. For instance, the 17% rate of increase in individual giving in 1986 was the highest ever to that point and has never been equaled since. The next year, 1987, saw the first decline in individual giving ever recorded in the 32 years Giving USA had been reporting gift totals.

A simple example can help illustrate how bunching deductions could at least partially explain this phenomenon.

Suppose Pamela was a regular donor of $5,000 per year. In 2017, she was told that she would probably not be able to fully itemize her gift in 2018 due to higher standard deductions and that, even if she could, the deduction would be worth less because her tax rate was going down. In December 2017, she was advised to make her gifts in the 2017 tax year, so she wrote a check for $10,000.

As a result, her donor record (and the charity’s gift income) would show a spike for 2017 and a smaller gift or perhaps no gift at all for 2018. Organizations with wealthier and more sophisticated donors may well have experienced this phenomenon on a larger scale than others for 2018.

But the good news is that the impact on giving may just involve timing and not the total amount given. Donors who take advantage of this opportunity are generally looking for a way to harvest additional tax savings for one year rather than reducing their support long term. Regardless, history reveals that giving seems to recover rather quickly after the tax-induced aberration and prior growth trends resume as donors adjust their planning and expectations.

Advised funds may have cushioned impact

One final point of interest: Industry press reported the greatest increase ever in the opening of new donor advised funds (DAF) and the increased funding of existing ones in late 2017 and continuing into 2018. Anecdotal reports indicate that some donors, especially those who normally give larger amounts, may have bunched their deductions in 2017 by making a large contribution to a DAF before subsequently spreading the actual transfers to charity over more than one year.

For instance, in the earlier example, Pamela could have given $5,000 to a charity in December of 2017 while also contributing $5,000 to her DAF. Because she directed a transfer of the second $5,000 to the same charity in 2018, the charity would not have actually realized the bunching occurred despite the fact that Pamela experienced the enhanced benefits of the bunching on her tax return for 2017.

The broad expansion of the use of DAFs in this way may help cushion the cash flow impact that bunching can have on charities over time, and fundraisers should be aware of the possible use of the DAF for this purpose as they interact with donors now and in the future.

In a similar vein, for donors age 70½ and older, making gifts directly from their IRA can also preserve prior tax benefits without the need to bunch gifts. That is because these funds do not flow through their tax return and are not subject to tax whether or not the donor continues to itemize.

Stay tuned for an update on 2017 giving when the IRS releases final figures for that year at some point this summer. ■