Editor’s Note: This article is excerpted from Mr. Sharpe’s closing plenary session at the National Committee on Planned Giving (NCPG) National Conference on October 14, 2006. The presentation will also be made at planned giving councils in New York, Chicago, Cleveland, and San Francisco in early 2007.

Webster’s defines marketing as “to offer for sale in a market.” If we are “marketing” planned gifts, then what exactly are we “selling?” Are planned gifts “products” that return more tangible benefit than they “cost” a donor? Are we closing sales of financial products?

Despite the impression one might receive from those who promote planned gifts as a panacea for all one’s financial and tax woes, that approach is misleading at best and even dishonest at worst. Consider, for example, that charitable gift annuity rates are intentionally set by the American Council on Gift Annuities at a level well below comparable commercial annuities—a level at which gift annuities return less financial benefit to the donor, even after considering tax savings. Can a donor really come out ahead with a charitable remainder or lead trust? No. If they could, such plans would be a staple of every wealthy individual’s planning, regardless of donative intent.

What are we selling?

The truth is that if we are “selling” anything, it is the ability for donors to satisfy intangible needs that spring from spiritual, emotional, political, or social motivations—and often at levels they might not otherwise have thought possible. What we are doing is making possible the process of transferring wealth from the private sector, where it is created, to the nonprofit sector, where it is put to uses that our society has determined are best met by not-for-profit, non-governmental agencies. To the extent that certain conditions are met, all or a portion of the income or assets involved are sometimes exempted from various taxes. All this means is that it costs less to make the gift, not that it costs nothing.

What, then, shall we define as marketing success? Few institutions enjoy an asset base that allows them to invest in fund raising activities that will result in gifts that will only mature at the deaths of donors in 10, 20, 30 years or even longer. Therefore, success in planned gift marketing must in most cases be defined as helping donors make gifts that will provide funds to meet mission needs in a reasonable period of time at an acceptable cost level.

For example, if an institution produces 50 gift annuities of $30,000 each from 65-year-old couples, the face value of the gift annuities is $1.5 million. Under the assumptions underlying the American Council on Gift Annuities (ACGA) rates, the expected remainder is $1,240,000. This amount will be received in 25 years on average. If funds received today could be invested for 25 years at an 8% return, the present value of that $1,240,000 is just $181,000.

If, on the other hand, the same $1.5 million was made up of the same number of gift annuities from 78-year-old couples, the expected residuum is approximately the same at $1,215,000. It should, however, be received on average in 14 years. The present value of the residuum in this case is $413,000.

Suppose the cost allocated to producing these gift annuities was $35,000 in both cases. For the 65-year-old group, the cost percentage would be 20%, while it would be a much lower 8% where the average age is 78. This is the math that FASB rules and other accounting policies will increasingly dictate be applied to determine the costs and benefits of planned giving. Thus, success in planned gift marketing will be based not only on producing funds that can be devoted to mission within a reasonable time frame, but also doing so at an acceptable cost level.

Which leaves us with the current environment. Investment markets are now at record levels. This bodes well for increased levels of both outright and deferred gifts. At the same time, demographers tell us there will be little or no growth in the 70 to 90 age range over the coming decade, and death rates will be relatively flat over that time period. Demographic trends thus foretell a flattening of the number of bequests and other planned gifts from this age range in coming years.

The Baby Boom Generation is now beginning to swell the ranks of those age 60 and older. This is good news for annual giving, traditional capital campaigns, and other forms of fund raising that are cost effective in that age range. Keep in mind, though, that the life expectancy of a 60-year-old couple is currently 30 years, making it difficult to produce funds that will be received anytime soon using planned gifts that only produce funds at the death of a couple this age or younger.

Our conclusion, therefore, is that success in planned gift marketing insofar as bequests, gift annuities, and similar gifts are concerned must be defined as continuing to cost-effectively encourage estate gifts from persons primarily in the 70+ age range.

What is planned giving?

In order to succeed in producing more planned gifts, it is also important to define the term “planned gift.” We define a planned gift as follows: “A planned gift is any gift of any kind for any amount given for any purpose—operations, capital expansion, or endowment—whether given currently or deferred if the assistance of a professional staff person, qualified volunteer, or the donor’s advisors is necessary to complete the gift. In addition, it includes any gift which is carefully considered by a donor in light of estate and financial plans.” Give & Take, Vol. 20, No. 4, March 1988.

This definition of a planned gift is based on the premise that every gift has five elements: who makes the gift, why do they make it, what do they give, when is the gift completed, and finally, how is the gift structured.

In some organizations, one group of fundraisers is expected to concentrate on the “who” and the “why” of gifts. That group would typically be those responsible for direct mail, the annual fund, major gifts, or a capital campaign. In other programs a separate group will be told to focus primarily on the “what,” “when,” and “how” of the gift. That is sometimes referred to as the “planned giving” or “gift planning” function.

Programs that succeed in the future will be the ones that successfully integrate the gift planning process with other fund development efforts. Programs that continue to pursue “planned giving” or “major giving” in a vacuum—separate from each other and/or other funding efforts—will increasingly find it difficult to succeed by any definition.

Over a decade ago, we first introduced a concept that approached fund raising primarily from the perspective of the age and wealth of donors, rather than the size of gifts, their timing, or the needs of the charitable entity for current, capital, and endowment funding.

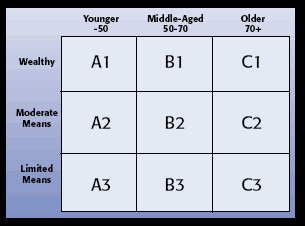

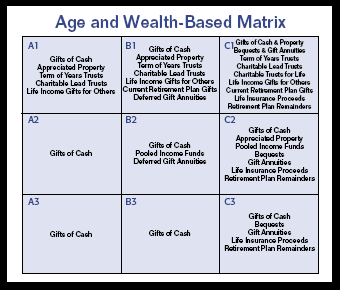

The Sharpe Matrix™ starts with the premise that all donors fall into certain age ranges, for our purposes three groups—those under age 50, those age 50 to 70, and those over the age of 70.

Every donor will also fall into a category of wealth we refer to as high wealth, average wealth, and those of limited means. The wealth amounts are relative and will vary by type of institution.

Combining these two categories, every donor falls into one of the nine boxes depicted below:

We believe that it is important in today’s environment to approach fund raising with those in various boxes in different ways. Surely, for example, an approach that will succeed with an A1 may fall on deaf ears in the case of someone in the C3 box, and vice versa. Everything from mission focus, to communication means, to graphic elements in published materials should ideally be designed from the perspective of who it is intended to influence.

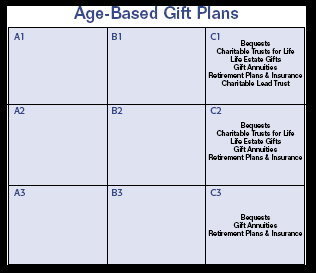

The gift planning tools at our disposal also vary in their applicability depending on the age and wealth of donors. While there is room for slight differences in the group that each plan applies to, some gift planning tools, like gift annuities and bequests, are primarily applicable to those in the C category. For example, ACGA studies show that the average age of new gift annuitants is 78, with few persons under the age of 70 entering into gift annuities.

Likewise, the final wills that name charitable recipients are normally executed by persons in their late seventies. IRS data indicates that people with taxable estates who die before they reach age 70 rarely leave bequests to charity.

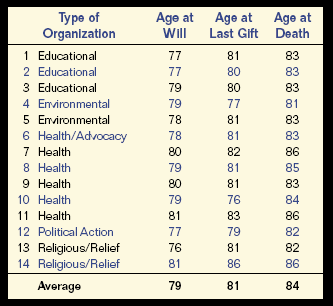

While other studies have indicated some may first include charities in their wills in their forties, the will that ultimately results in charitable dispositions is the last will. Therefore, to influence bequests, we must focus on influencing the behavior of persons in the 75+ age range. To underscore this conclusion, consider the following chart that illustrates the average age at will, last gift, and death for 14 different organizations that each studied 100 or more recent bequest gifts:

Thus bequests and gift annuities, charitable remainder trusts for life, and certain other plans are primarily age-oriented in their appeal:

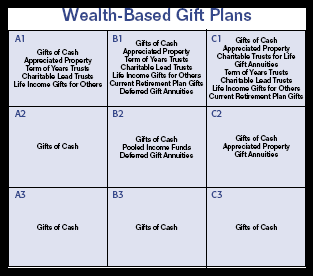

On the other hand, another category of “planned gifts” appeals to donors primarily based on their wealth rather than age. Gifts of appreciated assets, charitable remainder trusts for a term of years, charitable lead trusts, and others tend to be more applicable across the top of the Sharpe Matrix™:

All of the vehicles we refer to as “planned gifts” find a home in one or more of the matrix boxes, depending on the age and/or wealth of the donor:

Note that a number of planning tools such as IRA rollovers are only applicable in the C1 box because they are restricted to persons over the age of 70 who are wealthy enough that they don’t feel they need all of their retirement funds.

This brings us to the inevitable overlap area between “planned” and “major” gifts. What if one department is handling a segment of donors because they are rich and are “major donors” while another department is interested in the same donors because they are older and are “planned giving” donors? In this case a growing problem may loom ahead as major donors are increasingly found among the ranks of older, wealthy individuals who reside in the C1 box, where the greatest overlap between planned and major gifts tends to occur.

Moving in circles

Consider this. If one person is in a rowboat pulling as hard as possible on only one oar in one direction, the boat will almost certainly move in circles. If two people are in the boat, each pulling on an oar but in opposite directions, then the boat still moves in circles—only faster. To succeed in “planned gift” marketing now and in the future, those who are working with major donors and those who are involved in planned giving must see themselves in the same boat and pulling their oars in the same direction.

That means an increased need for cooperation between staff responsible for various aspects of fund development. This also means that smaller programs with less division of labor may have an advantage. Why? Because larger programs with multiple departments may be wittingly or unwittingly competing against each other for their donors’ attention. Greater familiarity with the basic workings of gift plans among donors and their advisors may accentuate that advantage over time.

Matrix-based marketing

Instead of looking at the matrix from the outside, imagine you are a donor looking out at your organization and its fund development efforts from inside various boxes in the matrix. What does a person in the C1 box see? Is it different from what a person in the C3 box sees? Do they perceive your organization differently depending on their level of wealth and giving capacity and where they are in their lifecycle? Should you communicate the same messages to them in the same way? Not if you want to succeed in coming years.

A younger person in the A1 box may be invited to events, be cultivated for larger gifts, be a prime candidate for a campaign gift, etc. Most communication will be in person or via e-mail and donor-initiated visits to your Web site. That person’s grandmother in the C2 or C3 box may, on the other hand, be in her final years as a donor, be reducing the amount she gives currently, and contemplating a gift annuity or the provisions of her final will. In that case, there is at least an 80% probability that she does not own a computer and has never and will never be online. She relies primarily on the printed word for information, and has a VCR (not a DVD player) that has been blinking midnight for 20 years.

Our means of communication must therefore vary depending on age, wealth, education level, and other factors. Much has been said about the need to utilize the Internet in planned gift marketing. It is indeed important to make information about charitable gift planning available on-line for donors and advisors. But that should be done in the context of the matrix described earlier.

A tangled web?

The vast majority of persons who are online are still under the age of 70. Think for a moment about what that means for those who are charged with influencing gifts from persons who are primarily in the 75+ age range. When some marketers declare that “seniors” are the fastest growing online group, “seniors” are often being defined as those over age 55. The latest information from leading authorities at the Pew Charitable Trusts shows that just 17% of persons over the age of 75 are actually online. Of that group, just 4% have high-speed access for convenient browsing.

Keep in mind that the average age of persons who enter into charitable gift annuities is 78 and the median age is closer to 80 in most cases. And recall that people are making final bequest decisions at about the same age.

This information underscores the fact that it is increasingly important to use e-mail and other Web-based techniques to communicate giving opportunities to younger donors. When using e-mail blasts and similar approaches, however, consider that, with one or two key strokes, the donor may send all future e-mail to a junk file and you will not get through again. Also consider that most persons in their fifties and sixties are still working and are besieged by e-mail from all directions. The rapid proliferation of handheld devices used to screen and respond to e-mail among younger persons may mean fewer persons can easily access links to Web sites imbedded in e-mail. The most savvy marketers might want to consider skipping e-mail and moving to text messaging for younger donors on the go.

Some, including those raising funds for education, may have an edge in that more of their older donors may be online. They also have the advantage of actually having access to more e-mail addresses.

But consider the case of a typical organization outside higher education. If the organization has 10,000 donors over age 75, the Pew study indicates that approximately 1,700 of them are online. If it has e-mail addresses for 10% of those persons, it has the ability to reach 170 people, or 1.7% of its donors over age 75. Research shows that seniors who are online are most likely to limit their activity to e-mail and do not regularly browse or rely on sites for financial and other information. Physical limitations based on age-related degradation of vision, attention span, short-term memory, and manual dexterity also come into play.

A recent Investment Company Institute survey, for example, showed that only 2% of those over 70 said they went to the Internet for information on their IRA withdrawals. They said they relied on talking directly to advisors and on printed material. (See www.ici.org/pdf/per11-01.pdf , page 20.)

Also keep in mind that when we send an “e-brochure” we are asking an elderly person who may or may not have a functional printer to use a significant portion of an ink cartridge. This should be considered when designing material intended to be printed.

Those who decide to rely totally on Web-based marketing for planned gifts that require older donors to pass away should expect to influence few new gifts. They may, however, find support among their colleagues who still rely heavily on mail and other print-based fund raising because they have not been able to make strong headway with online fund raising with most donors, especially older ones. They may thus welcome the departure of the planned giving program from the mail cycle. The same may not be true for those who are afraid that too much communication with younger donors on the subject of planned gifts may divert attention away from efforts to encourage outright gifts to capital campaigns and other major gifts.

The truth, like it or not, is that few persons who will die and leave a bequest or create a gift annuity anytime soon are online. It is not difficult, however, to prompt a 55-year-old to request information regarding a bequest online. An e-mail blast to a large number of relatively younger people will almost certainly result in responses from those entering the age range when they may be first seriously considering estate planning. This activity may well help influence gifts that will come to fruition in 30 years. In the meantime, it may create an excellent opportunity for follow-up by a major gifts officer who sees this as a chance for a favorable, donor-instigated interaction. A well-integrated program may thus decide it is appropriate to market bequests to younger people to find good prospects for major current gifts.

Does all this mean we don’t need Web-based information? Of course not. Does it mean that we should rely on that method with persons who are in the age range to do planned gifts that are cost effective in the near term? Not if we want to be viable over the next decade.

Ironically, those who continue to use traditional communication channels as their primary communication with the conventional market for planned gifts may find greater receptivity among older persons who begin receiving less mail as some organizations thin out the mail by opting to market planned gifts to a younger universe of donors through more active use of the Web.

Mixing media

The answer is to mix our media. Across the top of the matrix, the use of the Internet with younger people will be increasingly effective. Information should be available about gift planning ideas that are appropriate for relatively younger persons. In the C1 box, most of the proactive communication will continue to be controlled by those responsible for major gifts, campaigns, and other initiatives aimed at the wealthy of all ages. In the C2 and C3 boxes, where most age-related planned gifts originate, information should be readily available online for the minority of donors who choose this means of communication, while regular mail, articles, and other more traditional means of communication will continue to be the mainstay.

Is e-marketing an ill-advised fad? No. Is it a marketing panacea? No. Do not succumb to the temptation to rely on the marketing concept de jour. Over the past 25 years we have seen various methods of marketing proclaimed as the “coming thing.” This includes segmented direct mail, planned giving videos, 800 numbers, computer-aided research, seminars for donors, seminars for advisors, broadcast faxes, and others. All have found a place in planned gift marketing and so will e-marketing over time. None are exclusive, and Web-based communication will not be, either.

There is a big difference between the donors who are on one side of the Internet divide or the other. As those now entering their retirement years age over the coming decade, they will continue to use the Internet into their later years as a technology to which they have already adapted.

Satellite radio hasn’t destroyed traditional radio. We don’t all read books online as experts predicted a decade ago. We don’t microwave all of our food, even though it may be faster and cheaper than cooking in a conventional oven. Most use microwaves to heat food cooked in traditional ways. New technologies often supplement and promote growth but rarely replace. We have to supply what our market—the donors—want, and that varies by age. If donors tell you they want to correspond by e-mail, do that. If they prefer mail as evidenced by their behavior in their other interactions with your organization, take that cue as well.

Those who succeed in planned gift marketing in the future will do so only by carefully considering their fund development approaches in light of the age and wealth of their donors, the nature of their mission, and many other factors. For those who are able to shape their message differently for those at various stages of life, a bright future lies ahead.