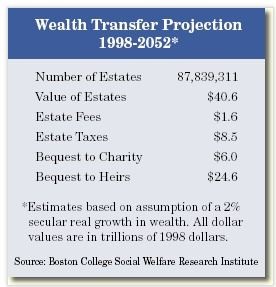

In 1999, near the peak of the economic growth of the 1990s, Boston College released a study projecting an intergenerational estate transfer of at least $41 trillion, a figure four times as large as amounts previously projected by economists at Cornell University. In “Millionaires and the Millennium: New Estimates of the Forthcoming Wealth Transfer and the Prospects for a Golden Age of Philanthropy,” John J. Havens and Paul G. Schervish predicted that at least $41 trillion in personal wealth would be transferred from the final estates of the 1998 adult population through the year 2052. Because this study’s projections far surpassed those of any previous study, both for- and nonprofit communities responded with great interest, and the popular press reported that baby boomers were eagerly awaiting their inheritance.

Projecting a bright spot for nonprofits

Although the $41 trillion figure initially seemed excessive to some, researchers at Boston College documented its validity, pointing to conservative growth and savings rate assumptions. Other projections were included in the study that assumed higher growth and saving rates and resulted in even larger wealth transfer estimates.

According to the Havens/Schervish study, America’s charitable sector could expect to receive a minimum of $6 trillion in charitable bequests as the wealth transfer unfolded. The mid-range estimate for bequests was $12 trillion, and under the most ambitious economic growth assumptions the bequest total was projected to be $25 trillion.

According to Giving USA, bequests have grown from $5.2 billion in 1982 to some $16.3 billion in 2001. This represents an average annual growth rate of 6.2% over that period. If the same growth rate continued from 2001 to the end of the transfer period in 2052, then charities would be assured of receiving just under $6 trillion. In other words, the low end of the estimated charitable wealth transfer for charity can be achieved with no greater growth in charitable bequests than has already been experienced over the past 20 years.

This is good news since America’s charitable community has greatly increased its efforts to encourage gifts via estates in recent years, and these efforts should serve to accelerate the rate of growth in this source of income. If the average growth rate increased to 8.25% per year, the mid-range projection of $12 trillion in charitable bequests in the Boston College study could actually be reached. A 10.25% rate of growth would result in the full $25 trillion being realized.

What a difference three years make?

Much has changed since 1999—in both political and economic climates. In 1999, there was no immediate threat of war, and the economy had not yet fallen into recession. As these contingencies became reality, increasing questions and challenges were raised concerning the continuing validity of the wealth transfer estimates.

In light of these concerns, John S. Havens and Paul G. Schervish recently published a reexamination of their 1999 report. In “Why the $41 Trillion Wealth Transfer Estimate Is Still Valid,” Havens and Schervish reaffirm their original projections.

Because the low end of their estimates was originally based on conservative assumptions, the authors believe that their projection will not be affected by short-term fluctuations caused by periodic recessions and investment market losses. They also conclude that spending habits after retirement will not significantly affect their estimates since the asset value of wealthy Americans continues to grow after age 70. Any possible impact of longer life expectancies is offset by the trend toward later retirement, increased part-time employment, and the continued growth in wealth among the elderly wealthy.

Havens and Schervish further conclude that trends in annuitized retirement income will not negatively affect their estimates. They also reexamine the distribution of the wealth transfer among baby boomers and other heirs.

A windfall for charities?

The 2003 report does not address the possible impact of scheduled estate tax reductions on charitable bequests. However, the original report hints that no change would be expected: “The recent shift in the proportions allocated, especially by the super wealthy, away from heirs and toward philanthropy has occurred in the absence of any changes in estate taxes. Apparently something more profound than tax aversion and tax incentives is generating a greater predilection for philanthropy.” Other studies by Schervish have indicated that reductions in estate taxes may, in fact, lead to increases in estate giving by the very wealthy. See page 1 of the May 2001 issue of Give & Take (PDF or text) and the article “Charitable Giving and the Great American Wealth Transfer,” published in the June 2001 issue of Trusts & Estates and available at www.sharpenet.com/current.

Whatever occurs, the wealth transfer will not be evenly distributed. A small minority of charitable and non-charitable beneficiaries will receive relatively large sums, while many will receive little or nothing.

With no windfall assured, charities with sound plans to reach older, long-term donors, members, and friends will increase their chances of receiving a significant portion. For more information on the 2003 and 1999 reports, visit the Boston College Web site at www.bc.edu/swri.