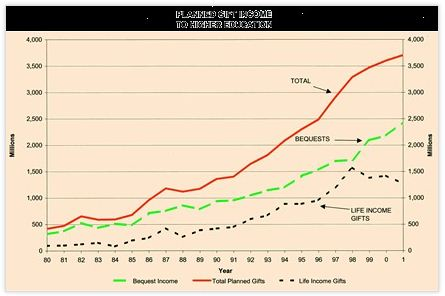

In March, the Council for Aid to Education (CAE), a subsidiary of the RAND Corporation, released a summary of its annual Voluntary Support of Education report. This report indicates that bequest income to reports colleges and universities in the year ended June 2001 amounted to a record $2.43 billion, an increase of 12% over 2000 figures. The growth in bequest income of a quarter of a billion dollars in one year was the second highest increase in bequest giving to higher education in history, exceeded only by the $377 million increase in 1999. See Figure 1 below:

Without the increase in bequest income, giving by individuals to higher education would have declined in 2001 for the first time since 1993. The report also indicated that gifts for capital purposes were flat, while gifts for current operations increased. Foundation grants also showed a large increase. The value of gifts of appreciated property, in most cases securities, dropped 8% as equity markets showed significant declines during the annual reporting period that ended June 2001. This is perhaps reflected in a decline in trusts and other life income gifts, the majority of which are traditionally funded with stocks and other appreciated property.

Bequests and economic conditions

Funds from estate distributions over the decades have proven to be a reliable source of gift income for higher education, declining in only one year since 1985. Bequest income appears to be relatively immune to business cycles, as death rates continue according to statistical norms during times of economic downturn. In fact, during the Great Depression, bequest income rose to percentage levels not seen again since that time. During that challenging period of America’s history, bequest income proved to be the primary source of growth for the few institutions that raised as much or more money during the Depression years than during the preceding years of prosperity. Ample historical evidence demonstrates that many of these schools had active planned gift development programs dating to as early as the 1890s.

As noted at the outset, gifts via charitable remainder trusts and other irrevocable deferred gift vehicles are somewhat more influenced by economic conditions as investment market valuations tend to affect the timing and amount of these gifts. See trends as depicted in Figure 1 above.

The accelerating wealth transfer

It has been estimated that the intergenerational transfer of wealth now taking place in America will total upwards of $41 trillion over the first half of the 21st century. It appears that the transfer of wealth has now begun to accelerate, and the latest CAE reports of giving to higher education further support this conclusion.

Educational institutions and other charitable organizations have traditionally been the recipients of billions of dollars Americans have voluntarily directed for purposes they wish to support. Since the early 20th century, the tax policies of the federal government and most states have encouraged this activity by exempting amounts left for charitable purposes from estate tax.

But is it possible to have an impact on the amount of funds left to charitable interests by donors as they plan their estates? The answer is “yes.” Many types of organizations outside the realm of higher education have also succeeded over the years in influencing the amount of bequests and other deferred gifts they receive.

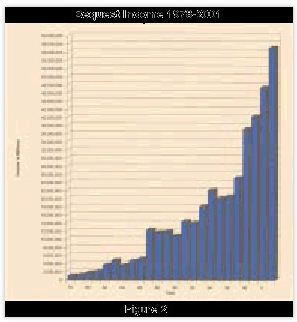

See Figure 2 that illustrates the growth in bequest income for one organization from 1978 to the present:

Organizations such as this one have succeeded in bequest development through concerted efforts to make their constituencies aware that they welcome and encourage such gifts. And many have found that these efforts can yield results in a relatively short period of time.

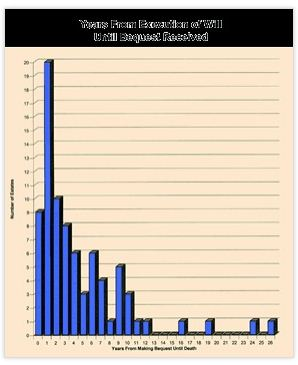

Note in Figure 3, for example, the lag times between the date of making a will that included a bequest to the organization referred to above and the date of death of the benefactor.

Surprisingly, for this organization, more bequests come from wills executed one year prior to death than any other year, and just under 60% of the wills that contained a bequest were executed within three years of death. This could indicate that efforts to influence bequests can, in fact, show measurable results within a relatively short time period. In fact, in many cases it appears a bequest may be very similar to a major gift decision made by those who know they may be nearing the end of their lives. If such persons have not made the outright gifts they had wished to make during life due to economic conditions or other reasons, they may be more inclined to leave funds through his or her estates.

A bequest via a will is just one of many ways a person can choose to direct funds to charitable purposes through their estate. Some methods involve the creation of specialized transfer vehicles such as gift annuities, charitable remainder trusts, charitable lead trusts, and pooled income funds. Other methods involve the use of plans donors already have in place for other purposes, such as retirement plans and life insurance policies.

Bequests by will and living trust remain, however, the most common source of planned gifts to higher education, for example. According to the CAE report referenced above, approximately two-thirds of planned gifts to higher education in 2001 came in the form of realized bequests from wills. This figure has averaged 68% over the past two decades.

Looking to the future

For some segments of the nonprofit sector, the coming years may represent a time when the average age of their donor base is older than ever before. This will be a natural outgrowth of the fact that over 70 million Americans, some 25% of the 2002 population, will pass the age of 65 over the next two decades. This is, in turn, due to the tremendous increase in the birth rates in the United States between 1935 and 1955.

Over the coming decade, many nonprofits will be finding that 40% or more of their donors are beyond the age of 70, and are at a time in life when they are beginning to plan for the ultimate distribution of the assets accumulated over their lifetime. The average age at death for bequest donors is in the early eighties with final plans made in their late seventies. As a result, given the demographic trends outlined above, the potential for continued growth in bequests for charitable purposes over the next few years appears unprecedented.

Time to plan

The steps that charitable organizations and institutions take in coming years to adapt their fundraising to demographic realities may mean the difference between years of struggle and years of healthy growth in total funding. The group of people now moving into the later stage of life are the wealthiest generation in American history. Beneficiaries of the G. I. Bill, they fueled growth in annual giving programs in the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s as they worked to build America. They were the backbone of capital gift development efforts in the 1980s and 1990s as they benefited from growth in investment markets, and they now stand ready to make transfers through their estates that may collectively dwarf the amounts they gave during their lifetimes.

Now is the time to begin to position your organization to receive its share of the philanthropy that will occur as a component of the wealth transfer that is now unfolding. For many, the charitable bequest will be the gift of choice. Others will be looking for ways to provide income for themselves and others for life or another period of time. Some will respond to communications directed to trusts and other deferred gifts and will actually make their gifts via bequests. Others will indicate interest in a bequest through their wills and then give through a life income gift plan as they are made aware of the tax and other financial benefits of these alternatives.

Increase current funding as well

While it is vital to communicate with older donors and other friends on the subject of philanthropy and estate planning, don’t forget to periodically include younger donors in bequest and other planned gift development efforts. People who indicate they have included a charitable interest as part of one’s estate plans, or are considering doing so, at a relatively young age can be among the best prospects for increased current giving. It is important to keep in mind that the decision to include a charity in one’s estate plans with no financial or other tangible benefits can be an extremely reliable indicator of a substantial level of donative intent. Studies have shown that the average age when people first include charitable interests in their will is 49.

Act now to assure maximum participation in the ongoing transfer of wealth occurring in America. Those that adjust their fund development efforts in appropriate ways over the coming years stand to benefit from opportunities that may not occur again for decades.

Editor’s note: The CAE numbers are based on the results of reporting institutions. See www.cae.org for more information or to order the report. For more on the scope of the transfer of wealth in America, see www.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/gsas/swri and click on “Research Projects.” For more on charitable giving during the years of the Great Depression, see the March 2002 Trusts & Estates magazine article entitled “Philanthropy in Uncertain Times” by Robert F. Sharpe, Jr. The article can be downloaded from www.sharpenet.com/current.