Most charitable organizations and institutions that rely on charitable gifts for a substantial portion of their funding have guidelines in place for what types of donations will be accepted—and then for what purposes they may be restricted. But in order for such policies to be effective, they must be appropriate for both the particular organization and the current economic environment. Well-thought-out gift acceptance policies are especially important for programs that actively encourage bequests, deferred gifts, and gifts of real estate and other non-cash property.

Types of property accepted

In recent years, as investment markets have fluctuated while real estate values have continued to rise in many areas, a number of programs have seen a marked increase in gifts that involve real estate. Some organizations that have policies in place that severely restrict gifts of real estate are taking a fresh look at these guidelines in order to avoid rejecting what may, in fact, be very valuable gifts. Other programs with more lenient policies have learned from experience the need to tighten procedures governing real estate gifts in order to avoid repeating unfortunate mistakes.

How much is enough?

Lower interest rates and yields on other investments have led some programs to review their policies on the maximum payment rates allowed for charitable remainder trusts and lead trusts. These and other plans can suffer unacceptable levels of encroachment of principal if maximum payment rates are set in accordance with expectations that were commonplace in the 1990s.

It may also be necessary to alter default values in software used to project benefits for donors so that they reflect lower total return assumptions. More and more organizations are restricting who is authorized to set investment return assumptions in gift illustrations. Failure to do so can result in the embarrassing situation of a gift acceptance committee’s rejection of a gift offered in response to a development officer’s proposal.

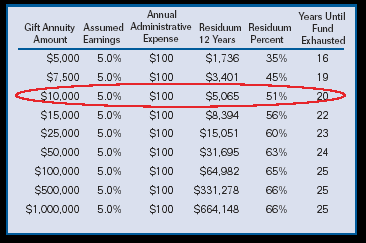

Administrative expenses may also necessitate adjustments in the minimum amounts necessary to fund a particular gift. For example, assume that the average cost of administering a gift annuity for a particular organization is $100 per annuity per year. For a $10,000 gift annuity, that amounts to 1% of the initial gift annuity amount. If the organization pays the 7.1% rate recommended by the American Council on Gift Annuities for a 75-year-old, then a $10,000 gift annuity that costs $100 per year to administer should result in a residuum amount of just over $5,000, or 50% of the amount transferred, assuming the donor lives 12 years. The Council rates are designed to yield an average residuum of 50%, so this is in keeping with the desired outcome.

Suppose, however, that the organization accepts gift annuities of less than $10,000. As we can see from the chart below, the $100 per annuity expense is fixed and applies to gift annuities regardless of their amount. A 5% return assumption on the annuity funds may cause some organizations to decide that they do not wish to accept gift annuities in amounts that would yield an expected residuum lower than the recommended levels.

The chart below illustrates why larger gift annuities may yield much greater benefits as a percentage of funds initially transferred than smaller gift annuities.

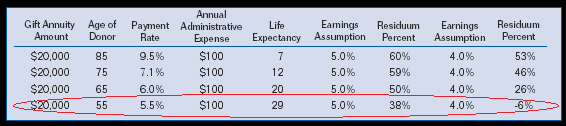

Future earnings assumptions must be taken into account as well when setting minimum ages for gift annuities and similar plans. Note that as long as earnings assumptions of 5% are met and administrative expense is maintained at $100 per gift annuity, there is no problem achieving or exceeding a 50% residuum amount for older donors. If earnings fall to 4%, however, just 1% short of expectations, residuum percentages remain in acceptable ranges for older donors but may fall into negative territory for younger persons.

Gift acceptance policies should thus take into account a number of factors including earnings assumptions, administrative expense levels, the expected time period until receipt of the gift, and others when setting minimum gift amounts and ages for various gifts. Some programs may need to adjust policies that were set at a time when different assumptions were appropriate.

Examining restrictions

Experienced fundraisers know that donors will often give more when they feel they have involvement in deciding how the funds will be used. Organizations that do not allow donors any input in how their gifts are applied can find it difficult to raise large amounts from relatively sophisticated donors.

But just as the economic landscape changes over time, so do organizational needs. In good economic times when an organization is experiencing steady increases in funding, it may be possible to impose a broader range of restrictions on gift dollars than is possible in more challenging economic times. For this reason, sections of gift acceptance policies that address permissible restrictions and minimum amounts required to place restrictions on gifts may also need to be examined periodically.

It can be constructive to take a proactive approach. Rather than actively limiting restrictions on gifts, a better strategy may be to “carve out” a number of areas of interest. Based on various mission components, areas of geographic emphasis, or other discreet “thought sectors,” such proposals can lead donors to a level of comfort regarding the use of their gifts without unduly restricting them.

Also, consider incorporating a statement that enables donors to approve language that would allow the chief executive officer or other appropriate party to alter the use of funds with the approval of the board or other governing body. This will cover instances where a particular program or service for which funds are restricted is either overfunded or no longer exists.

Keeping the peace

Besides controlling costs and helping to channel funds to appropriate areas of program emphasis, well-considered and current gift acceptance policies can also help maintain harmonious staff relations and foster better relationships between donors and those assigned to steward relationships with them.

By involving staff from development, finance, program administrations, and other areas of organizational management along with volunteer leadership from the board in the process of creating and reviewing gift acceptance policies, a spirit of teamwork and mutual understanding can be enhanced. Those who are not involved in the day-to-day activities of fund raising can gain a greater understanding of what drives the development process before the gift is completed. Likewise, those who work directly with donors can gain a greater understanding of the issues faced by those who must meet the expectations of donors after the funds are actually received.

Policies that are rooted in consensus of senior staff and reduced to written form can also be very beneficial in helping to preserve relationships with donors when a gift must for one reason or another be rejected. If the donor can be furnished with written policies, it is much easier for the fundraiser “on the ground” to handle any negative reactions. Written policies remove focus or blame from the contact person and make it clear that the rejection of their particular gift is the result of policies that had been considered and determined in the past. A donor may even gain a greater respect for the professionalism of an organization that is prepared to quickly respond to an offer to make an unusual gift.

Finally, gift acceptance policies can be an excellent tool for training new and existing staff. After updating policies each year, consider holding a series of staff training sessions to explain any changes. New staff will gain confidence, and veterans will feel reassured that their management is in tune with the times. All staff will feel that your organization has taken all steps possible to assure that they can relate to donors in a way that communicates a commitment to the highest levels of service and excellence.

Editor’s note: Learn more about gift acceptance policies and other important issues in Sharpe’s popular seminar “An Introduction to Planned Giving.” See page 3 for details on this seminar and page 8 for a listing of all Sharpe seminars in 2005.