Over the years, we have worked with many people who were new to the process of charitable gift planning. As they begin, the issues related to types of properties donors can give, the tax consequences of gifts, and the economics of structuring gifts can seem overwhelming. Add to this the multitude of motivations that underlie gifts, and the various needs the charitable recipient must meet in the areas of current, capital, and endowment funding, and newcomers as well as veterans can quickly feel they are losing control of the process. An orderly approach to planning major gifts, whether current or deferred, can minimize unnecessary confusion and lead to maximum gift potential.

To help in the process of structuring significant gifts, we have developed a tool to help guide you through the process. What we refer to as the “anatomy of a gift” can be helpful in organizing your thinking. By carefully considering the “who,” “why,” “what,” “when,” and “how” of a larger gift, the pieces of the puzzle can be put together in ways that produce gifts that might not otherwise come to fruition.

Who is the donor?

At the outset, it is important to consider “who” the donor is. Consider their age, their gender, their marital status. Do they have children? What do you know about the prospective donor’s lifestyle? If it is a couple, are both equally interested in making the gift? What are their priorities? What other charitable interests are they known to support? The more you know about the donor and who they are, the easier it is to understand the other elements that comprise the gift.

Why will the donor give?

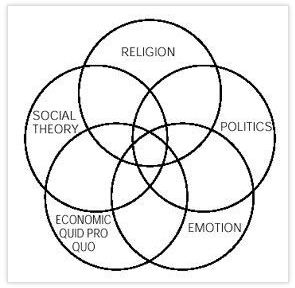

The “why” is the most complex element of the gift. Donors give for many, many reasons. A casual observer of fund-raising campaigns in America today might be led to believe that tax savings and recognition are the primary motivators for charitable gifts. While these are important considerations for many donors, they are only part of the picture. What are the important motivators? After observing the motivations of donors in a large number of gift situations, we believe that donor motivations can be reduced to five main categories.

Religion is perhaps the most common motivator for charitable gifts. The majority of charitable gifts in America each year are made to religious-based charities. According to Giving USA, in 1999, some 43% of charitable gifts were received by charitable recipients with religious affiliations. Studies have also shown that many gifts made to secular causes are made from religious motivations as well. While religious beliefs are very personal to donors, understanding them where possible, and being sensitive to their impact on the charitable gift planning process, is critical to helping donors make their gifts most effectively.

For example, in a number of religious traditions, making gifts anonymously is important to experience the greatest spiritual benefit from giving. When working with a donor who is motivated by such religious beliefs, it can be a major mistake to offer a naming opportunity or otherwise emphasize recognition for a gift when that is the last thing the donor is seeking, and may actually be interpreted as insensitivity or impugning the true motivation for their gift.

Social motivations are another major factor that influence charitable gifts. Donors who are not motivated by religious beliefs may nevertheless embrace beliefs in the way society should be organized that include the duty to share with others and invest in social infrastructure. This is where concepts such as noblesse oblige come into play. Such motivations are often found when dealing with persons with inherited wealth who have been taught as part of their family tradition that they have a duty to help meet the needs of society. Philanthropy has long been one of the behaviors that has been expected of those who would be community leaders and members of the most influential social circles.

Political beliefs can also come into play. Some donors are adamantly opposed to government taxation and spending and do not believe in systems that they believe amount to the involuntary transfer of wealth. Within that group there are some who believe in “every one for themselves,” while others believe that they are stewards of capital and have a duty to reinvest it for the benefit of mankind in a voluntary system of wealth redistribution. Still others believe in European-style social democracy with high taxes, major government benefits, and little or no private philanthropy. Understanding where donors fit on the political spectrum can be key to helping them decide whether, when, and how to make their gifts.

Emotional motivations could be the subject of a series of volumes. Virtually every human emotion can be the motivator behind a gift. In many cases, it is really a combination of a number of different emotions. Consider, for example, the complex forces at work in the mind of a person who has been asked to make a major gift to a university medical facility that is doing state of the art research on a disease with a significant hereditary component that took the life of his wife of 40 years, where the same institution recently rejected the undergraduate application of a grandchild who had always had his heart set on attendance there.

Naming opportunities are another area where emotions come into play. The temptation in the area of emotional motivations, because the knowledge of them is “portable,” is to overemphasize them at the expense of a greater understanding of motivations inherent in the mission of the organization that may take longer to master. One must also be very careful in this area, as in other areas of motivation, that knowledge of donors’ deepest emotional concerns does not lead to manipulation of those desires. This is one of the most important areas where personal integrity plays a vital role in fund development efforts.

Economic Quid Pro Quo is perhaps the most misunderstood of the motivators for charitable gifts. While it is true that there are significant tax benefits associated with some gifts and it is possible to enjoy income, asset management, and other financial returns associated with various planned gifts, it is a dangerous fallacy to assume that these factors are actually the root motivator for gifts. Remember that the tax benefits for gifts are the same regardless of the recipient and the payment rates for gifts and other economics are very similar in most cases. The paradox is that in today’s environment it is absolutely vital to understand the economics of larger charitable transfers, but it is also important to realize that those economics in the final analysis rarely motivate the gift itself. A recent NCPG-commissioned study affirms this fact. The most successful gift planners put the “gift” before the “plan,” and know that it is difficult if not impossible to romance a plan to the point that it can become the “why” that attracts the “who.”

It is rare to find any one of the above motivators as the only motivation for a gift. In the author’s experience, most larger gifts involve complex interrelationships between a number of these factors. Understanding the “motivational molecule” depicted above is the key to success in arriving at the correct gift solution.

The “what,” “when,” and “how”

After one gains a greater understanding of the root motivators for charitable gifts, then the other pieces of the puzzle tend to fall into place. What property is chosen to make a gift may be determined partly by economics, partly by emotion. The timing of when a gift is made may also be influenced by many factors. Finally, the “how” the gift is made, or the vehicle chosen to transfer assets, will become apparent as a way to accomplish multiple objectives utilizing the best possible property.

Charitable gift planning is fun. Charitable gift planning is rewarding. Many of those who are best at it often wonder at the fact that they actually are paid to do it! But that level of satisfaction is not something that happens automatically. When we get behind plans and try to push them or get in front of donors and try to pull them toward our plans, it can be a frustrating process that lacks essential rewards.

Through understanding the nature of the very human factors that underlie basic motivations and using economic tools to help facilitate transfers, we can walk beside our donors and help guide them in the process of accomplishing things they might not otherwise believe possible in ways that feature rewards for all parties to the process. Have fun!