Recently much attention has been paid to the tremendous amount of wealth that has been lost as equity markets have declined over the past three years. The values of stocks that had been considered “growth” stocks throughout the 1990s have fallen the most. Certain sectors of the economy, such as high tech and telecommunications concerns, have fared worse than others.

As has been noted in the financial press, however, those who remained conservatively invested in high-grade debt instruments and in companies involved in the production of staple products have lost less than others, and may even enjoy greater wealth than during the boom period they patiently watched pass them by. Included among these investors are many seniors who naturally tend to invest in bonds and higher yield, stable securities because they are retired and need reliable income.

Impact on endowments

Some charitable organizations and institutions are included among the investors who avoided what Alan Greenspan in hindsight termed the “irrational exuberance” of recent years. Because of relatively low exposure to more troubled segments of the investment universe, these charities have seen little, if any, decline in the value of their endowments and may have even experienced increases.

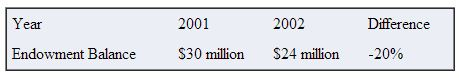

Unfortunately, other nonprofits have suffered fairly significant losses in their endowment funds. Take the case of one organization:

This organization has experienced a 20% decline in the value of its endowment, amounting to a loss of some $6 million. While this decline is cause enough for concern, its ripple effect will be having an even broader impact on the financial health of the organization and its ability to fulfill its mission.

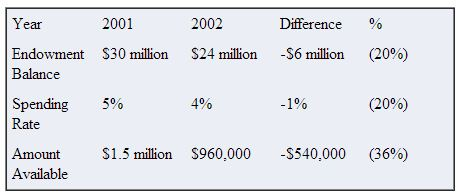

In recent years, this organization has budgeted an amount equal to an average of 5% of the value of endowment funds for current operations. The $1.5 million generated by the endowment fund last year will thus, of necessity, be reduced for the coming year. But by how much? In planning for next year’s budget, the organization realized that projected lower returns over the next few years will not realistically allow the 5% spending rate to continue. The budget committee of the board decided to reduce the spending rate from an amount equal to 5% of the endowment balance to a sum representing just 4% of the value of the endowment.

Here is the impact of that decision on the budget for the coming year:

Note that the combination of the 20% decline in endowment asset values and the 20% reduction in the amount to be spent results in the need for a spending cut of $540,000, a reduction equal to some 36% of the amount available the year before. The most recent year’s total budget was $8 million. The required spending cut of $540,000 will thus amount to nearly 7% of the budget. In many organizations this would require the elimination or attrition of a number of staff positions.

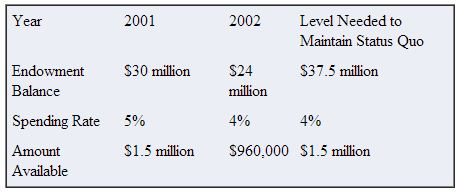

In preparing a report for the budget committee of the board, the chief financial officer determined that in order to restore its former fund generation capacity, the organization ’s endowment must grow from its current value by $13.5 million, or 56% ,to a new total of $37.5 million.

The committee decided that the likelihood of a 56% increase in market value of the endowment was remote. As other sources of funding were flat or down slightly, the committee also thought it unlikely that an increase in regular gift funding would make up the shortfall. It was also pointed out that legal restrictions precluded invasion of the corpus of the restricted portion of their endowment. After much deliberation it was decided that a budget cut of the amount required to balance the budget should be its last resort and any other possibilities should first be exhausted.

Four-step recovery plan

How might a creative and resourceful organization prudently act to repair the damage done to its endowment? The best approach may not be a simple one; a multi-faceted approach will in all likelihood need to be considered.

Step 1: Every effort should be made to reduce costs in all areas except fund development, assuming fundraising cost percentages are within acceptable levels. If fundraising expenses are too high, steps should be taken as quickly as possible to eliminate whatever expense is necessary to bring costs into line without causing a reduction in net income.

Step 2: Efforts should be undertaken to discover constituents who have pursued investment strategies that have resulted in their maintaining or increasing their wealth in recent years. Some investors have learned the hard way to keep their success in the market to themselves, so they may not be as easy to identify as in past years. One way to coax these “needles” from the “haystack” is to send all donors reminders of the efficiency of gifts of securities, especially in times when fewer persons have gains. Some donors may make a gift of securities to show their support. But don ’t be surprised if these persons request total anonymity, a trend we are noticing among many of the “angels” who are surfacing and giving a boost to flagging programs these days.

Step 3: A very small, very exclusive funding campaign may be considered. This would be a “campaign” that would break all the traditional rules. There would be no naming opportunities. It is difficult to “name” unrestricted funds intended to function as reserve funds or quasi-endowment. There would be only a small number of donors and few, if any, gifts would be announced. The donors who would participate are the small handful who are sophisticated enough to understand how an organization could lose 20% of its endowment when many others were up slightly, broke even, or were down just a few percentage points. They may even be many of the same persons who helped to make the endowment investment allocation decisions and/or chose the asset managers or consultants who made or condoned those decisions.

These donors might not necessarily make gifts that would permanently replace the lost endowment funds. Their gifts may, for example, be made in the form of charitable lead trusts. The lead trust is, after all, a form of “temporary endowment.” If nine individuals were to place $1 million each in charitable lead trusts paying just 6% to the organization for a term of 15 years, the organization could use the $60,000 per year from each of the nine lead trusts to “replace” the entire endowment spending shortfall of $540,000 for each of the next 15 years.

At the end of 15 years, heirs chosen by the donor would receive what remained in the trust. If, as many of these wealthy individuals may still assume possible, the trusts earned a total return of 8% over time, then their heirs would receive approximately $1.6 million at the termination of the trusts. The donors would be encouraged to use their own financial services providers to establish and manage the actual trusts.

The donors would file gift tax returns and report $1 million gifts to heirs but would then be entitled to an offsetting charitable deduction of some $672,000, leaving a $328,000 taxable gift that could be eliminated in most cases by the $325,000 additional gift tax exemption available as of January 1, 2002. If both spouses participated, each could establish a $1 million trust and just four or five couples could thus replace the funds no longer available from the endowment. In case the $325,000 exemption amount has already been used, the donor could increase the payout rate to 7.5% and provide for the trust to last 18 years. This would result in a gift tax deduction that would shield $995,000 of the $1 million placed in the trust from taxation.

A solution like this might be thought of as an “endowment patch,” as the lead trusts serve to temporarily solve the spending problem, while buying time for the organization and its volunteer leadership to find a more permanent solution.

Step 4: This leads to the fourth step the organization may wish to take. Many organizations will find that history will reveal that much of their current reserve fund and quasi-endowment was realized as a result of “saving” unrestricted bequests and the remainders from trusts, gift annuities, and other deferred gifts, rather than spending the funds on current operations.

In that case, the final step an organization that has suffered endowment losses might take to help bring about a permanent solution is to step up efforts to encourage more gifts via wills, trusts, and other planned gift vehicles. As the average time from making a will until death for wills that prove to be the source of a charitable bequest is between three and five years, efforts undertaken today can yield benefits in the relative near term at low cost. In our example, assuming an ongoing, viable mission, the organization should be able to permanently replace the temporary endowment “patch” funds well before the lead trusts terminate and the revenue stream ceases.

Endowment mirror trusts

In appropriate cases, the organization described above might also want to encourage the lead trust donors to establish charitable remainder trusts using $1 million that would pay them 6%, or $60,000 per year for 15 years. If the trusts earn 6% per year total return, then at the end of 15 years the remainder of each trust would be worth $1 million, and would “replace” the funds that would be leaving the lead trusts at that point and no longer be available to generate funds for the charity. As the trusts work in tandem over the same time period to temporarily, and then permanently, replace lost endowment, they might be referred to as “endowment mirror trusts.”

If the donors also created remainder trusts to replace the lead trusts when they terminated, they would be entitled to a charitable income tax deduction of over $374,000 for the year they establish the trust. They may also avoid or delay capital gains tax on appreciated assets used to fund the trusts. Over the 15-year term of the trust, they would receive payments totaling $900,000. This amount could be used to purchase substantial amounts of insurance to add to the inheritance being received by the donors’ heirs at the termination of the lead trust.

Responding to challenges

The needs of most organizations and institutions will not be shrinking in coming years, whether or not their endowments have declined. Fortunately, over the years many tools have been developed that can serve to “stretch” or “patch” endowments while we await recovery of value and/or permanent replenishment from traditional sources.

Now is the time to act to show those who care most about the future of your organization that there are ways to fund your mission now and in future years—while still meeting their need to assure future financial security for themselves and their loved ones.