As the new year unfolds and the fund-raising efforts of 2008 are tallied, we see mixed results. Some are up, some are down, and some are flat. But one thing is certain—2009 will not be business as usual.

History indicates giving in America tends to hold relatively steady during recessionary periods, and may not decline as much as the overall economy. We are no longer in an environment, however, where a rising tide will raise all boats.

The key to success in today’s environment is knowing where to focus efforts in ways that will produce the most funding, and what to trim to maximize those results. Some cuts are obvious. Lavish events, for example, may be the first to go. Or perhaps development officers should now add a day or two to a trip and use the time to make additional donor visits or combine visits with training or other needs, and therefore stretch one airline ticket to do the work of two.

With a little planning and creativity, it may be possible to cut costs without a commensurate reduction in funding.

Here’s a cost-saving idea you’ll probably hear: “Why not cut the planned giving program?” After all, it takes years to show results from such efforts, and this can always be done later when the dust settles. Now is the time to focus on the “real money.”

Unfortunately, to a greater or lesser extent, in the coming months some will take this approach—an approach that is completely understandable in light of some of the recent misdirected “advice” of “experts” in the field.

If a major priority of your organization or institution is to encourage notification of bequest expectancies from 45-year-olds, then “pausing” costly efforts to market such gifts may make a lot of financial sense in today’s environment.

For many, however, their planned giving program represents a framework for helping donors make gifts as part of their final estate plans.

In addition, it may include helping donors of all ages make near-term gifts while confronting and neutralizing natural financial objections that may otherwise preclude the completion of those gifts. If this describes your situation, then your planned gift efforts may have never been more critical.

The best gift planning efforts represent ways to help donors make larger gifts they genuinely want to make during times when their usual methods of giving may seem too risky or would deplete their resources before first meeting other needs.

An “extended” pledge?

For example, which might a donor prefer—a pledge that requires five annual payments of $100,000, or an alternative gift such as a transfer of low-yielding stock through a simple agreement that immediately reduces the donor’s tax burden, provides a predictable, fixed income for five years, and then funds a $500,000 endowment with a single transfer at the end of a five-year campaign when the donor also retires?

Is this a “major” gift? A “campaign” gift? An “endowment” gift? A “special” gift? A “leadership” gift? An “alternative” gift? Or is it a “planned gift?”

Do you present this to a donor as an opportunity to fund a fiveyear, term-of-years charitable remainder annuity trust? Or do you ask if they might be interested in a “balloon pledge?”

What about bequests?

Cutting mass marketing of bequests to people with 30- to 40-year life expectancies is a move that can help reduce costs without negatively impacting results in the near term.

See the summary of the recent survey conducted by the American Council on Gift Annuities on page 4. The ACGA concluded that targeted mailings were one of the most effective ways to encourage bequests and other planned gifts.

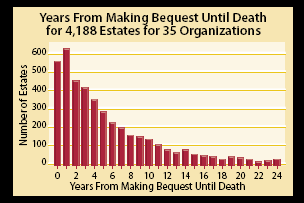

Study after study reveals that wills that actually leave funds to charity are most often completed by persons in their late 70s to early 80s. Forty years of in-depth research by Sharpe consultants on thousands of realized bequests indicates that approximately 50% of them came from a person who executed their will within three years of death.

The chart illustrates lag times for over 4,000 estates from 35 selected organizations representing education, healthcare, religion, social services, and other types of organizations.

This is why influencing a relatively small group of older, long-term donors who are at the point in life where they are making their final plans can positively impact your results within three to five years.

But what about earlier wills? Don’t you want to be in the first will? Of course you do! People normally write wills throughout their lives when they marry, have children, retire, or lose a spouse.

People’s interests change over time, however, and they actually leave funds to the charities that they are actively supporting at the time they execute their last will. If the charities they supported earlier in life, and included in earlier wills, remain a part of their lives, then those charities will likely still receive a bequest. If, on the other hand, the donors’ charitable interests changed over time, their last wills may include a different set of charities than their first wills.

There are other more cost-effective ways to keep the bequest message in front of younger people (the web, for example).

Programs mailing bequest packages to donors in their 50s or even younger may be able to save a great deal of budget money by letting the Baby Boomers and X’ers mature a few more years. Keep in mind that a 45-year-old enjoys a life expectancy of just under 38 years. Where were you in 1971? Where will you and your organization be in 2047?

Many managers have understandably concluded, however, that continuing to target age-appropriate messages to a smaller group of donors with life expectancies of 10 years or less on average may be a more cost-effective use of scarce bequest marketing funds.

Gift annuity communications efforts should be targeted in much the same way. Now might be the time for those marketing gift annuities to younger persons to step back and analyze their results to see how many annuities have actually been completed by those under the age of 70.

Take a look at these numbers and then determine whether the gift annuity marketing dollars directed to younger people might be better spent on more donor visits and other activities that may yield results sooner.

Where your younger donors are concerned, it may be more productive to target appropriate persons with information about deferred gift annuities, term-of-years trusts, life income gifts for older relatives, gifts of securities, charitable lead trusts, and other ways to give that they might find more useful in today’s environment.

Defining your future

If planned giving includes substantial funds aimed at encouraging younger donors to make gifts that will not be realized, on average, until they pass away in four decades or longer, then you may find this is a legitimate place to make some strategic cuts.

If, on the other hand, you want to help donors give to your organization in the most efficient, cost-effective way for a person of their age and wealth profile, you will cut planned giving at your organization’s immediate and long-term peril.

Nonprofit organizations and institutions that survived and prospered during the Great Depression did so, in many cases, because their income from bequests and other planned gifts grew faster than other gifts declined. Bequests and other estate-based gifts influenced in 1931 resulted in useable funds in many cases by 1935.

These gifts came from committed donors, many of whom were moved from the current to deferred gift category late in life due to economic circumstances.

Today we must all conserve resources in every way possible. But we must conserve in ways that continue to provide donors and their advisors with the assistance they need to make the gifts, both current and deferred, that they still want to make to the organizations and institutions they care most about.

Editor’s note: The content of this article is based on information in the popular Sharpe seminar “Planning Major Gifts.” For more on giving during economic downturns, see www.sharpenet.com/uncertaintimes.