Over the course of my career, I have often been asked by nonprofit development executives, financial officers, board members and others how long it takes for efforts designed to encourage bequests and other planned gifts to produce a return on investment (ROI).

Common wisdom in the field is that a planned gift development effort can be expected to begin yielding measurable results in as little as three to five years. A number of factors can materially affect that outcome, including the demographics of a particular constituency and the level of marketing and stewardship efforts. If metrics that include new estate commitments are included, the “return” on investment can be almost immediate. For purposes of this article, however, we will focus on results as measured by actual distributions received from estates.

Following the data.

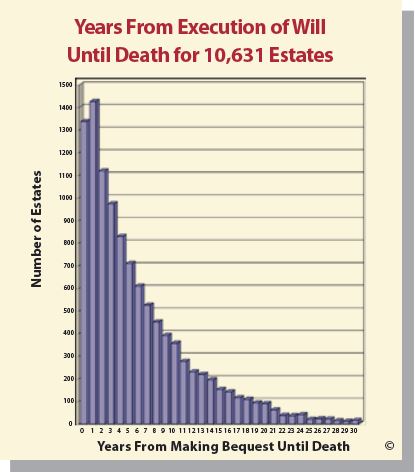

Over the past 50 years, Sharpe consultants have analyzed thousands of actual estate gifts received by scores of organizations and have accumulated a repository of data known as the Sharpe KnowledgeBaseSM. This data indicates that the most common time period between the execution of a will that contains a charitable bequest and the donor’s death is just one year. See the chart at right for an analysis of one group of more than 10,000 representative estates from a large number of organizations of different types.

Over the past 50 years, Sharpe consultants have analyzed thousands of actual estate gifts received by scores of organizations and have accumulated a repository of data known as the Sharpe KnowledgeBaseSM. This data indicates that the most common time period between the execution of a will that contains a charitable bequest and the donor’s death is just one year. See the chart at right for an analysis of one group of more than 10,000 representative estates from a large number of organizations of different types.

When situations in which a donor dies the same year the final will is executed are also considered, the data indicates that some 25 percent of bequests nationwide come from those who pass away within one year of executing the will. Just over 50 percent of bequests come from those who pass away within four years of signing their final will and 83 percent within 10 years.

These statistics are borne out by findings in recent studies by Professor Russell James of Texas Tech University, whose longitudinal study conducted over a 20-year period found that 85 percent of bequest dollars are received from those who pass away after age 75 and 50 percent of those bequests are received within five years of the date the final will was completed. According to Dr. James’s research, in more than 50 percent of cases, bequest donors reported having plans with no charitable beneficiaries within five years of death.

Those who find these statistics surprising may want to test them against their own experience. Simply look at charitable bequests received over the past few years and compare the date of the execution of the will with the date of the donor’s death. Over more than 50 years of study of these factors, the Sharpe Group has rarely found an organization’s experience to deviate from these norms in any appreciable manner.

The reasons for this phenomenon involve the interplay of several factors: gender, marital status, wealth, absence of children, mortality concerns and other determinants.

Keep these facts in mind

The key to influencing bequests and other planned gifts, and in so doing maximizing return on investment over a relatively short time frame, is to be aware of a few truths that guide many of the most successful programs.

1. Studies indicate that as many as 50 percent of Americans die without a valid will. In such cases, there will obviously be no charitable distributions at death. This is why it is important to keep information about the need to make or update a will or other estate plans in front of an appropriate group of donors on a regular basis.

Those persons who do execute a will normally only do so a limited number of times. The dates wills are executed often coincide with major life events such as a change in marital status, the arrival of children or grandchildren, impending retirement, awareness of approaching mortality or the death of a spouse or other loved one.

2. Persons who have never married or had children typically execute fewer wills over the course of their lifetime than others. They generally execute their final will in the face of illness or advanced age when they are confronted with the fact that inflexible state laws may cause their assets to be distributed to relatives they may not even know. This is an important fact to be aware of, as this group is among the most likely to leave charitable bequests in their final wills.

3. The timing of the final will varies for each individual and is not predictable in any given case, so consistent communication is vitally important.

4. As obvious as it may seem, charities that are included in final wills are the ones that are most important to the donor at that point in time. These are the charities that come to mind when donors are asked if they would like to include charitable provisions in their estate plans.

For these and other reasons, the most successful programs know it is vital to keep messages encouraging bequests and other planned gifts in front of those donors who are statistically most likely to soon be making their final wills. In addition, if proper stewardship is not undertaken, a particular charitable interest may not be top of mind when the donor is executing the final will, increasing the risk that the charity will be left out even if it had been listed as a beneficiary in a previously executed will.

Trimming costs or trimming income?

What does all of this mean at a time when many charitable entities are looking for ways to trim budgets without causing a near-term reduction of income? In too many cases, management and volunteers may conclude that cuts in planned gift marketing and stewardship budgets are “safe” because it could be many years before the impact of these cuts will be felt. Makes sense, right?

Not so fast. What goes up in three to five years can come down just as quickly. Consider the economy. It has now been a full five years since the onset of the Great Recession and the budget cuts many nonprofits experienced in its wake. If effective planned gift marketing and communications efforts can show benefits in three to five years, then logic dictates we should now be seeing the effects of neglect where inappropriate cuts were made.

Not so fast. What goes up in three to five years can come down just as quickly. Consider the economy. It has now been a full five years since the onset of the Great Recession and the budget cuts many nonprofits experienced in its wake. If effective planned gift marketing and communications efforts can show benefits in three to five years, then logic dictates we should now be seeing the effects of neglect where inappropriate cuts were made.

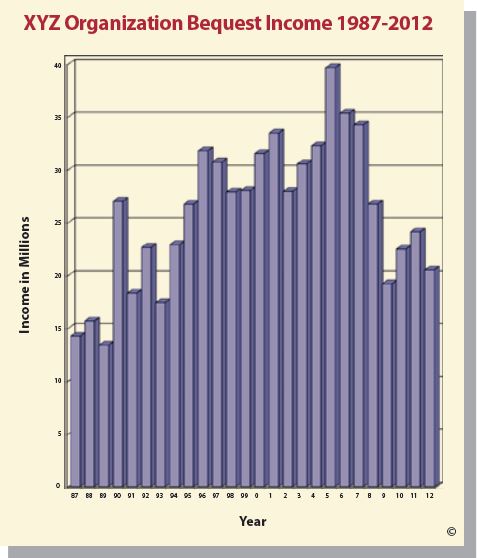

Note the dip in bequest income experienced by the following organization that dramatically reduced its bequest marketing and stewardship efforts in the mid-2000s.

At this organization, bequest donors on average do not make their first gifts to the organization until their mid to late 70s. The organization attempted to save costs by dramatically reducing new donor acquisition efforts while simultaneously decreasing its planned gift marketing and stewardship efforts. Reductions in new donor acquisition and other expenditures in this case led to a precipitous decline in bequest income within a matter of a few short years, following a 20-year period of solid growth.

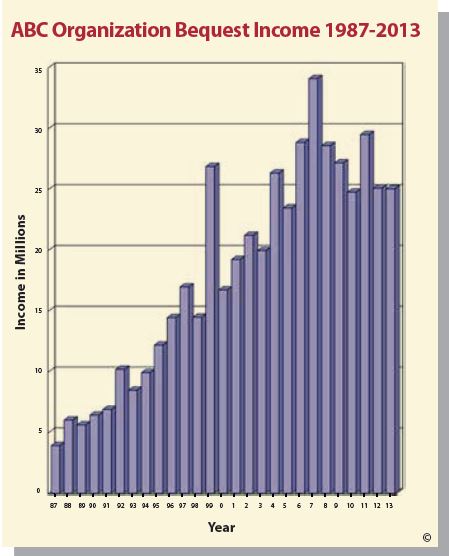

Is this an isolated case? Unfortunately not. The chart below shows results from another organization that had enjoyed strong growth in bequest income for many years before experiencing a sharp decline.

This organization not only cut back on new donor acquisition to some extent but also abruptly switched its planned gift marketing from print to online e-marketing beginning in 2005. Unfortunately, this organization did not realize that the average age at the time donors fund gift annuities is 79 and bequest donors, as noted previously, are normally in the same age range when making their final will.

This organization not only cut back on new donor acquisition to some extent but also abruptly switched its planned gift marketing from print to online e-marketing beginning in 2005. Unfortunately, this organization did not realize that the average age at the time donors fund gift annuities is 79 and bequest donors, as noted previously, are normally in the same age range when making their final will.

The switch to email-based marketing took place at a time when less than 20 percent of persons in that age range were online. Recent Pew Foundation reports reveal that 62 percent of persons over age 77 are still not online. As a result, this organization inadvertently stopped communicating with as many as 80 percent of its prospective planned gift donors.

Bequest income and numbers of realized bequests both dropped by significant amounts within three to five years after traditional marketing was curtailed. Similar results were experienced in the numbers of new gift annuity commitments.

While this organization increased web traffic from younger persons seeking free will planning kits and discovered a number of bequest intentions from younger persons with life expectancies of 25 years or longer, this approach had little or no impact on donors over 75, the majority of whom were not and are still not online.

Unfortunately, now that this strategy has proven to be harmful, it will take another three to five years to arrest the decline and effect a meaningful reversal. By that time, the program will have experienced 10 years of interruption in growth and approximately $50 million in lost bequest revenue, all to save a small fraction of that amount on more age-appropriate marketing and stewardship efforts.

Where is the balance?

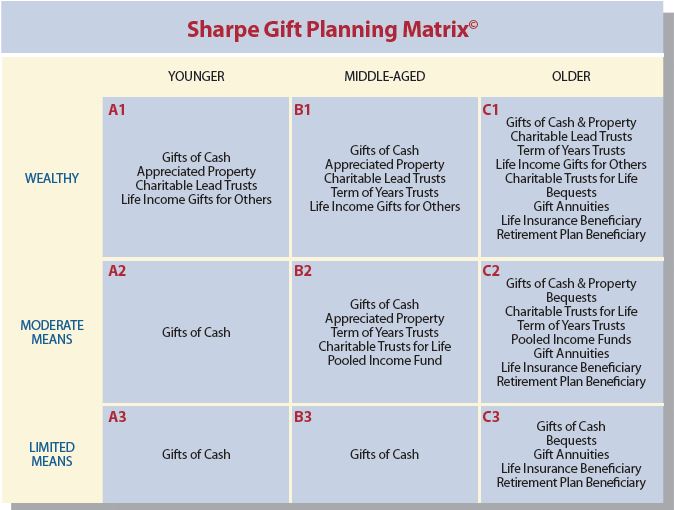

In the current environment, pressure to spend fundraising dollars wisely will continue, if not intensify. Cost-effective solutions will differ for every program. The place to start is by knowing the age and wealth of your donors. The Sharpe Gift Planning Matrix© was developed a number of years ago to help facilitate this process.

Where bequest and other age-sensitive gift planning options are concerned, savings can be effected and results increased by focusing limited resources on the oldest among your constituency. Don’t neglect younger donors, however. A younger donor who reveals a bequest intention can be an excellent source for ongoing giving, including major gifts in some cases. The bequest concept can be kept in front of younger donors through “background” marketing such as gift acknowledgment inserts, ads, articles, tag lines of stationery and other means that are less costly than targeted communications. Online marketing can also be a cost-effective way to plant seeds that will bear fruit in decades to come.

The correct tool for reducing planned gift marketing costs is a scalpel, not an axe. Careful adjustments of marketing and staffing levels should only be undertaken after a thorough study of the demographics of your constituency and consideration of your mission. The goal should be to reduce costs in the near term in a responsible manner without causing a negative impact on funds received in the future.