On May 28th, President Bush signed into law the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003. The stated goal was to stimulate a sluggish economy by providing federal income tax relief for many Americans. The primary thrust of the bill is to accelerate income tax rate cuts that were already planned for coming years as part of the provisions of the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001. It also contains a number of other changes to our nation’s tax laws, some of which can be expected to affect the ways in which larger charitable gifts are structured.

The recent Tax Act does not, however, directly address charitable giving. During the negotiation process in Congress, lawmakers carefully structured the bill to disassociate it from the charitable giving provisions contained in the CARE Act and similar bills introduced in recent months that are specifically designed to stimulate charitable giving. As a result, for example, the bill did not change the tax treatment of gifts from IRAs and other retirement plans, and did not provide for a deduction for non-itemizers or other measures designed to encourage charitable giving. (As we go to press, the CARE Act and similar bills are under consideration in the House and Senate, with their eventual fate still unknown.) The bill also made no changes in the schedule for the reduction and/or eventual elimination of gift and estate taxes that were an integral component of the 2001 Tax Act.

The primary provisions of the 2003 Tax Act are listed below:

- Decreases in income tax rates. The maximum ordinary income tax bracket for 2003 will be 35%, down from 38.6%. The brackets above 15% will be reduced to 33%, 28%, and 25%. Other changes apply to lower tax brackets that will result in tax reductions for persons subject to those rates as well.

- Relief from the “marriage penalty” for many taxpayers.

- Lower taxes on capital gains and dividend income.

- Increase in the amount of the childcare credit.

- Reduction of the impact of the alternative minimum tax.

- Incentives for investment in business equipment.

Impact on charitable giving

Although it does not directly target charitable giving, the recent Tax Act can still be expected to have an impact on the way gifts, especially larger ones, are structured.

First, by lowering tax rates, the net cost of a deductible charitable gift is increased. The formula for determining the after-tax cost of a charitable gift is as follows:

Cost = Gift – (T x Gift),

where T equals the applicable tax rate

Thus, the cost of a gift of $1,000 to a person in a 38.6% tax bracket would be $1,000 – (38.6% x $1,000), or $614, some 61.4% of the amount donated. With the reduction of the maximum tax rate to 35% for 2003, the formula would yield a maximum cost of $650, or 65% of each dollar donated ($1,000 – 35% x $1,000).

With gifts of appreciated assets, the formula is somewhat different:

Cost = Gift – (T x Gift) – c(Gift – Cost Basis),

where T equals the applicable ordinary income tax rate and c equals the applicable capital gain tax rate.

In the previous example, if a donor instead gave stock worth $1,000 with a cost basis of $200, under prior law the minimum cost would be $1,000 – (38.6% x $1,000) – 20% x ($1,000 – $200), or $454 (45.4% of amount donated). Under the new law, as a result of reductions in both the ordinary income tax rate (from 38.6% to 35%) and the capital gain tax rate (20% to 15%), the cost of the gift described above would be $1,000 – (35% x $1,000) – 15% x ($1,000 – $200), or $530 (53% of amount donated).

In these examples, the cost of the gift of cash by the highest bracket taxpayers will rise by 6% and the cost of a gift of the appreciated stock by 17%.

In the case of zero basis stock where the savings would be the greatest, the minimum cost of such a gift will rise from 41.4% of each dollar donated to 50% per dollar donated, an increase of 21%.

While the after-tax cost of certain charitable gifts will rise under the provisions of the recent Tax Act, it is important to remember that the costs of various types of gifts are relative; it will, for example, still cost as much as 30% more to make a gift in the form of cash rather than appreciated assets.

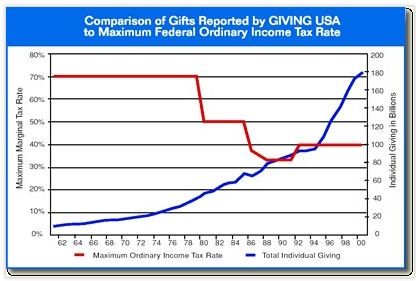

Despite a predictable and understandable litany of nay-saying in contemporaneous press reports, increases in the after-tax cost of charitable gifts in the past as a result of lower tax rates have not demonstrably affected the amount of charitable giving. This fact is reflected in trends in gifts by individuals reported by Giving USA for the years following reductions in maximum income tax rates brought about by past tax bills. See chart at right.

The message for donors is twofold. First, lower tax rates will make more cash available to donors for charitable gifts and other discretionary transfers of cash and other assets. Nonprofits should take this opportunity to encourage donors to use a portion of their after-tax income to support their charitable interests. Second, for those who have appreciated property, it still makes the most sense to donate the property and use cash to diversify investments. Don’t forget that many donors may now have increases in the value of bonds or bond funds as interest rates have fallen in recent years.

Impact on deferred gifts

Perhaps the most important impact of the new tax law for fundraisers is in the area of deferred planned gifts. Reductions in the rate of tax on capital gains and dividend income can actually serve to make certain types of gifts more attractive.

Gift annuities

For example, when donors fund charitable gift annuities with appreciated assets, a portion of each payment is taxed as capital gain for a period of time equal to their life expectancy. Lower capital gains tax rates mean they can keep more of the payments and achieve a higher after-tax yield than before. In some cases, this can be more than enough to offset lower annuity payment rates recommended by the American Council on Gift Annuities (ACGA) as of July 1, 2003.

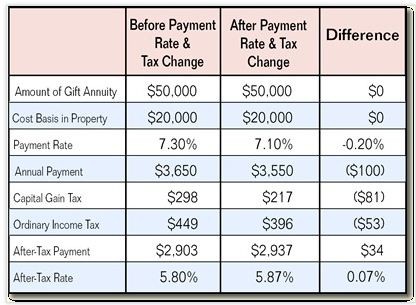

Consider a 75-year-old funding a gift annuity with $50,000 worth of stock that has a cost basis of $20,000. The chart on the right highlights the difference between a gift annuity established before and one funded after the recent ACGA rate changes and federal tax law changes.

Note that in this case, reductions in tax rates actually enable the donor to net more after taxes from a new gift annuity, even considering the reduction in rates recommended to go into effect on July 1.

Charitable remainder trusts

Similar results can be realized by taxpayers who fund charitable remainder trusts with appreciated assets. Under the so-called “tier structure” mandated for reporting income from charitable remainder trusts, the nature of income as realized within the trust maintains its character when reported on the recipient’s tax return. Thus, the percentage of income that retains its capital gain status may be taxed at a lower rate than under prior law. This will serve to make charitable remainder trusts funded with appreciated property even more attractive than before.

Consider also the impact of reducing the tax on dividend income. Presumably, dividend income will still enjoy its favored treatment when received by the income beneficiary of a charitable remainder trust. If this is in fact the case, then a donor may prefer a charitable remainder annuity trust to a gift annuity that pays the same rate if it is anticipated that the trust will yield dividend income that will be taxed at lower rates under the new tax law. The ordinary income element of a gift annuity payment, on the other hand, is taxed at full ordinary income tax rates with no differentiation of any portion of ordinary income derived from dividends.

While this may be an esoteric point, it is a helpful distinction when an institution is approached by a younger donor seeking a gift annuity that would offer relatively high payments. There may now be tax savings justifications that would lead the donor to opt for a charitable remainder annuity trust where liability is limited to trust assets and the gift does not amount to a general obligation of the charity.

In funding charitable remainder trusts and certain other split interest gifts, it may also be helpful to note that some assets will still be subject to much higher capital gains tax rates than 15%. For example, the amount of gain in real estate represented by the difference between the original cost basis and amounts deducted in the past as straight-line depreciation will be taxed at 25%. The gain in tangible personal property such as jewelry, art, and other collectibles will continue to be taxed at 28%. Thus, in appropriate circumstances, these types of assets may be better choices for funding gifts than property that would be taxed at lower rates if sold.

Charitable lead trusts

Lower taxes on capital gain and dividend income may also lead to increased interest in charitable lead trusts. Donors holding large amounts of appreciated property may be more likely to sell the property, pay historically low capital gain tax rates, and place the net proceeds in a lead trust. This amounts to, in effect, paying a 15% capital gain tax on part of the value of the assets rather than gift and estate taxes of up to 49% on the entire value of property transferred directly to non-charitable recipients.

The new law may also lead to increased interest in a plan sometimes referred to as a “Super CLAT,” under which a grantor lead trust enables a donor to remove an asset from his or her estate and enjoy a tax deduction today against an income tax rate as high as 35% while reporting income in later years that may be taxed at favorable capital gain and dividend tax rates. This latter point is another example of the subtle nature of the impact of the new Tax Act on charitable giving.

Where to go from here

As always, it is important to make certain that staff, volunteers, donors, and other constituencies receive the information they need in order to understand the impact of tax legislation on charitable giving. Sometimes the message is clear and direct; sometimes it is not as readily apparent. The impact of this law may seem negligible on the surface, but can have powerful implications for the funding and subsequent allocation of assets in the case of split interest gifts such as gift annuities, charitable remainder trusts, and lead trusts.

In communicating with donors, it is appropriate to make observations about the positive impact lower taxes can have on charitable gifts. Take the time to remind them that gifts of appreciated assets remain more advantageous than cash gifts. When making proposals for deferred gifts, help donors carefully consider which assets will help them take full advantage of the provisions of the new Tax Act.

By their very nature, tax law changes such as the one just signed into law alter the fund-raising landscape. Fundraisers that stay informed, remain resourceful, and help their donors navigate the new tax laws will chart a safe course to the future.