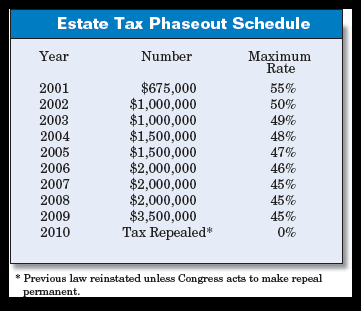

Ever since Congress first discussed reducing or eliminating the federal estate tax, many have speculated about the impact such action might have on charitable giving through estates. The following chart displays the scheduled elimination of the federal estate tax, which began in 2002 and will continue through 2010 when the tax is scheduled to be completely eliminated. Keep in mind that if the repeal is not made permanent, the prior estate tax law will be reinstated.

As we are now at the midway point in the estate tax phaseout process, now may be a good time to pause and reassess the impact of the estate tax reductions already in place and those scheduled to take effect on January 1, 2006.

Just the facts

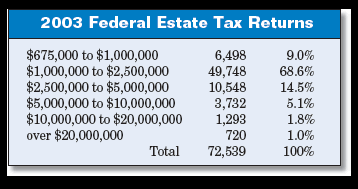

The Internal Revenue Service regularly releases valuable data based on its analysis of federal tax returns. Recently released information regarding federal estate tax returns in 2003 reveal that 72,539 estate tax returns were filed for that year from among the 2,497,000 persons who passed away that year.

Of the 72,539 total estate tax returns, more than 56,000 were filed by decedents whose estates totaled less than $2.5 million. While we do not yet know the number of returns for persons with estates valued between $2 million and $2.5 million, the IRS data indicate that in 2003 over 77% of the estates that filed returns were valued at less than $2.5 million.

As the estate tax threshold moves to $2 million in January, we are now entering a period when the estate tax has been effectively repealed for the vast majority of decedents in this country. For example, in 2003 only 16,293 persons died with estates over $2.5 million. That group represents just 6/10 of 1% of the 2,497,000 people who died in America in that year. Thus, beginning in 2006 it is estimated that less than 1% of Americans will still be subject to the estate tax. This would be the lowest percentage of persons affected by the estate tax since the 1930s.

Time to reconsider

In this light, it may be wise to re-examine the relevance of the debate about the impact of estate tax elimination on charitable giving. According to Giving USA figures released earlier this year, in 2004 Americans left some $19.8 billion in charitable bequests. Studies show that wills containing charitable disposition name approximately four charities on average. If the average bequest is in the range of $25,000, this would indicate that approximately 198,000 decedents leave bequests to charity each year. This number represents some 8 percent of the total number of persons who died last year. That percentage appears to be in line with an NCPG study in 2000 that indicated that some 11% of Americans planned to leave funds to charity (see “Survey of Donors 2000” at www.ncpg.org).

IRS data for 2003 reveal that 18.4% of all taxable returns that year included charitable bequests. By contrast, 26% of those with estates of over $2.5 million made a bequest to charity. That amounts to just 4,197 decedents in the entire United States with estates over $2.5 million who left a bequest to charity in 2003. This would represent just 2% of the number of persons estimated to have left funds to charity that year.

Given that perhaps 98% of persons leaving funds to charity receive no estate tax benefit as a result of their gifts, we may now have to begin thinking ahead realistically to the time when there may be no estate tax incentive for a charitable bequest for anyone. For many successful planned giving programs, it will not require any change in strategy to adapt to a world without estate taxes. Others, however, may be facing an “unlearning curve.”

Consider the emphasis many programs have placed on estate tax avoidance. Complex software programs and reams of projections tout “zero estate tax plans.” While this may still be an appealing idea for a very small number of donors, such emphasis will fall on deaf ears for the vast majority of those who support our nation’s charitable endeavors simply out of a desire to benefit their charitable interests. Consider that when donors put a charity in their wills, they receive no income tax deduction, no income stream, no recognition (for most), and, for an estimated 98%, no estate tax savings. These persons must be motivated by other factors. In fact, through their actions they are, in effect, elevating charities to the status of a close friend or family member.

New emphasis by planners

Given the fact that the estate tax has already been eliminated for most Americans, many advisors and estate planners will now begin to emphasize to their clients the need for new plans that take advantage of reduced estate taxes. Likewise, charitable entities may want to begin to consider non-tax-oriented approaches to encouraging donors to include charitable provisions in their wills.

Rather than bemoan the fact that little or no tax incentive remains for most donors to include charities in their wills, a better approach may be to view the glass have in planning their estates. Without a tax burden, there will be more “discretionary capital” in the estates of many, allowing for increased gifts to loved ones and charities.

Surprisingly, many donors may find that with these new freedoms they also face new challenges in planning their estates. In the past, many persons of moderate wealth chose to plan their estates in ways designed to take advantage of the marital deduction and other exemptions from tax. Many wills and other documents had come to be based primarily on “boiler plate” language designed to implement a fairly standard plan. Now donors will be free to plan their estates more in keeping with their personal priorities and values rather than tax-motivated formalities.

In the coming era of “post-estate tax” tax planning, it will be necessary to emphasize other reasons to change or update one’s plans such as changes in family status, marital status, state of residence, changes in persons who have been named to administer estates, and other factors.

Focusing on the right group

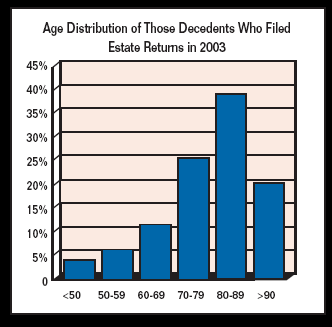

Looking at overall fund development efforts, the charities that do the best job of managing relationships with their donors will be the ones who are most likely to be included in the estates as people revise their plans in later years. Therefore, it is more important than ever to manage all aspects of relationships with older donors.

See the following chart for the ages of persons who died with taxable estates in 2003. The IRS figures in the chart below indicate that in fact around 57% of persons who died with taxable estates passed away beyond the age of 80.

A number of studies indicate that a significant number of persons begin to consider including charities in their estate plans at around the age of 50. As they grow older, increasing numbers act on those intentions and include charitable provisions in their plans. A number of leading nonprofits that have studied thousands of estates that include charitable bequests to their organizations have found that most wills that leave funds to charity are executed by persons in their mid to late seventies.

Other studies published by the American Council on Gift Annuities indicate that on average persons enter into charitable gift annuity contracts at 78.5 years of age. Charities that do an excellent job of cultivating older donors in general may find that they not only increase their prospects for charitable bequests but will find greater success in building their gift annuity programs and other planned gift development efforts as well.

The elimination of the estate tax was not a factor when the great charitable wealth transfer was predicted in the late 1990s. Whether or not the removal of this factor from the mix will make a significant difference remains to be seen. Recall, however, that nearly 25 years ago the estate tax was all but eliminated under the terms of the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 with the introduction of the unlimited marital deduction and the phase-in of a $600,000 exemption amount. Since that time, bequests have grown sevenfold.

The majority of charitable bequests are now received from non-taxable estates and to succeed in the future this must be even more the case. The organizations and institutions that grasp that fact and proceed accordingly will be the ones that will inevitably realize the most funding from estates in future years.

[Editor’s note: The preceding article is excerpted from Session I of Philanthropy in Times of Change. See page 3 for a complete description of the seminar as well as future dates.]