By: Robert F. Sharpe, Jr.

As the new year unfolds, many nonprofits are making plans for 2014 fundraising efforts or are continuing to implement plans already in progress. Taking time now to design a thoughtful fundraising strategy for the coming year can help ensure you meet or exceed expectations now and in the future.

This article outlines an approach to donor communication and cultivation that addresses the needs of various segments of your constituency based on a number of critical factors.

Getting started

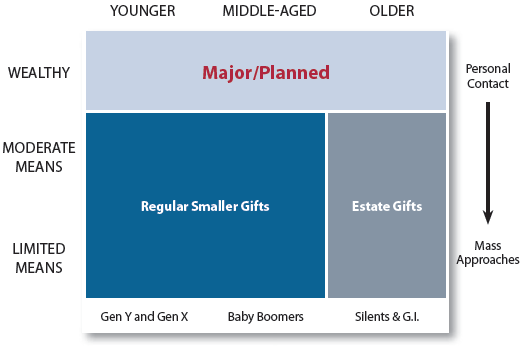

The Sharpe Gift Planning Matrix© is a helpful way to organize your constituents by age and approximate levels of wealth and income. For our purposes, we are dividing donors into three groups: under age 50, age 50 to 70 and age 70 and older. Wealth level divisions used to further segment your donors are more subjective, and the “splits” are often determined by the size of your constituency, staff capacity and other factors.

Note that the B column of the matrix closely matches the age of the bulk of baby boomers—age 50 to 68. Column A is comprised primarily of Gen Y and Gen X, while Column C is mainly the combination of the remainder of the Silent and G.I. generations.

Breaking it down

Let’s look briefly at each of the segments of the matrix and determine which gift planning strategies are best for each group.

C3 – Older donors of limited means

Experienced gift planners know it is important to cultivate this group. Some organizations receive the majority of bequests and gift annuities from these donors. A large number of donors in this segment are childless persons with relatively modest estates of perhaps $200,000 or less. When this sum is split among five charitable interests, the result can be five $40,000 bequests, an amount that is close to the national bequest average. It is not unusual for gift annuity donors to come from this group as well.

For these reasons, make certain not to exclude these donors from bequest and gift annuity marketing based on criteria such as past gift amounts and/or wealth ratings. Longevity and frequency of giving are much better indicators of interest among donors in the C3 category.

C2 – Older donors of moderate means

While very similar to C3 donors, this somewhat wealthier group is likely to have more valuable homes and to hold significant sums in IRA and other retirement accounts. These donors will often account for the largest number of bequests received and should be included in all communications related to estate gifts.

Some will also be prospects for gifts of cash or securities to fund life income gifts such as gift annuities and charitable remainder trusts.

C1 – Older wealthy donors

While fewer in number for most nonprofits, C1 donors are often the source of the handful of bequests that can make up 50 percent or more of estate revenue in a given year. Many programs will sometimes group the C1 donors with younger wealthy donors found across the top of the matrix. This group can also be the source of many of the largest outright gifts in a given year. The Chronicle of Philanthropy recently reported that the donors responsible for the largest gifts each year have an average age in the mid-70s, putting them solidly in the C1 box.

According to IRS reports, this group is responsible for the majority of gifts of stock and other appreciated assets. C1 donors are also more likely than other groups to be able to make gifts from retirement funds during lifetime or at death.

B1 – Middle-aged wealthy donors

At this point we take a “left turn” across the top of the matrix and continue our examination of the wealthier segments. There are strong commonalities among the A1, B1 and C1 segments. In many programs,the A1, B1 and C1 boxes are collectively managed as “major donors” because it is believed that the wealth of the C1 donors trumps their age from a communications and stewardship perspective.

The B1 segment should perhaps receive more attention than any other group this year. These donors are in their peak earning years and also enjoy significant levels of wealth in the form of real estate and other assets. For that reason, the primary goal is to help them structure immediate gifts in the most effective way possible. Their largest gifts, whether current or deferred, are most often made in the form of appreciated assets.

Keep in mind that a 60-year-old couple has a joint life expectancy of 30 years. Even the oldest in the B1 group could very well live for 15 years or more. For this reason, it is best to focus on gift planning options that can be realized in a donor’s lifetime. Examples include charitable lead trusts, charitable remainder gifts for terms of years or gift annuities and life income gifts designed to benefit a parent or other older loved one for life.

A1 – Younger wealthy donors

Persons under the age of 50, regardless of their wealth level, are rarely in or near their prime giving years. Building careers and raising families can naturally overshadow philanthropic impulses.

The bulk of information directed to this group should be focused on the acquisition and upgrading of donors. The small number of donors who express interest in making an estate gift at this age reveal a higher-than-normal level of donative intent and should be considered prospective major gift donors.

A2, B2, A3 and B3 – The rest of the matrix

The lower left sections of the matrix are where the largest number of donors and prospective donors may be found, especially in the case of educational institutions. These donors are normally only candidates for relatively smaller gifts of cash.

The key with donors in this age and wealth range is to acquire, retain and upgrade donors to maximize future success.

Putting it all together

While it is important to have access to specialists who can help address special factors related to “annual,” “major,” “capital,” “endowment” and “planned” gifts, success in a more complex and increasingly competitive market will require organizing efforts not simply around institutional needs, size and timing of gifts but also around the donor’s situation in life.

Marketing plans for each segment of the matrix should account for varying communications preferences. Those in the C2 and C3 boxes will most often respond best to mail and other traditional means of contact. Wealthier individuals across the top will often be given priority for personal contact along with information and tools to help them structure their gifts, whether current or deferred. Social media and other cutting-edge communications techniques should largely be reserved for the younger donors who represent the future of your funding efforts.