In the past, nonprofits typically counted bequests as “expectancies” or “maturities.” These expectancies usually included the amount of the expected bequest (when the details were known) or a conservative estimate (when the amount was not). Estimates were sometimes made using an average amount based on an organization’s experience.

Upon the death of the donor the bequest was moved from the expectancy list to what was often called the “maturity list” and was eventually reported for accounting purposes in the year the distributions were received.

Because of the fact that the largest number of bequests comes from smaller, non-taxable estates, the majority of bequests were never reported in IRS figures. Only charitable bequests from estates that fell over the federal exemption limit ($675,000 as recently as 2001) were reported on federal estate tax returns.

Many charities did not have a standard practice for counting the bequest for accounting purposes. Known bequest expectancies may or may not have been counted in campaigns or for other recognition purposes, whereas matured bequests were generally acknowledged in annual reports and other appropriate means only after they were received.

More than was expected

With no standard guidelines in place, it was not unusual for a single bequest to be counted several times for a variety of different purposes. For this reason, a decade ago the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) attempted to standardize reporting of charitable bequests. (See www.fasb.org for details.) Under these guidelines, unconditional promises to give are to be booked for accounting purposes. These include certain types of pledges, deferred gifts, and bequests where the donor has passed away (As they are unconditional following death, the charity has a right to receive them under state law.).

Yet some charities have continued to book charitable trusts and bequests for accounting purposes when not appropriate. For example, while qualified charitable remainder trusts are irrevocable, the majority of such trusts drafted today allow the donor to change the charitable beneficiary and therefore are not unconditional. Like a bequest, such charitable remainder trusts should not be reported under FASB rules until the trust terminates and the donor no longer has the right to change a particular charity’s interest in the trust remainder.

Similarly, charitable bequests by their very nature are conditional gifts because the donor may change his or her mind about the gift at any point until death. Occasionally, a donor may attempt to make a bequest unconditional by entering into a contract to make a bequest. This is most likely done in the setting of a capital campaign where the charity is relying upon the gift for a specific purpose. In such cases, some charities have included and reported bequest expectancies for campaign or recognition purposes even if they could not be counted for accounting purposes. While this practice may be desirable in the context of a campaign, when bequests are reported while still in the expectancy stage, care should be taken to assure that staff and volunteer leadership understand that bequests that are subsequently reported for accounting purposes upon receipt are not confused as “new” bequests if they have already been factored into the institution’s financial planning.

What FASB means for you

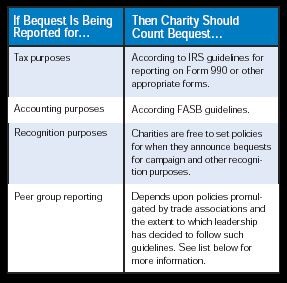

So how should you be counting bequests? The answer depends on the purposes for which they are being reported. See chart to the right.

Depending on the circumstances, it can thus be appropriate for the same bequest or trust remainder gift to be counted in a variety of ways. As bequests and other deferred gifts assume greater importance as a component of gift income, now may be the time for charities to review their gift counting and recognition policies to ensure they are consistent and in keeping with latest government and trade association guidelines.

June 2004

According to recent IRS figures, the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001 is beginning to have a significant impact on the number of federal estate tax returns that are being filed.

The number of estate tax returns projected to be filed for 2004 is 74,800, a 13.82% decline from 2003. The IRS projects the average annual percentage decline between 2004 and 2010 to be 18.20% per year. These decreases are primarily a result of the increases in the amount scheduled to be exempted from federal estate tax between 2002 and 2010.

Under the provisions of the 2001 Tax Act, the estate tax will be repealed in 2010 but will be reinstated the following year. At that time, the estate tax exemption equivalent reverts to $1 million, as provided for under the 1997 Tax Act

Listed below are the number of estate tax returns filed, estimated, or projected to be filed between 2002 and 2009, based on IRS figures.

Source: “Projections of Returns That Will Be Filed in Calendar Years 2004-2010” by Terry Manzi. Article available at http://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/04proj.pdf.

Putting it in perspective

Historically, estate tax returns have been an important source of information about the segment of the decedent population that makes charitable bequests. For example, we know from these returns that from 16% to 20% of estate tax returns filed each year report charitable provisions. The incidence of charitable bequests increases with such factors as the size of the estate, age, sex, and marital status.

According to other sources, such as the NCPG, about 8% of the general decedent population includes charities in their estate plans. If, as data suggests, only half of the decedent population has a valid will or other estate plans in place, the 8% must come from the 50% with a will, meaning that some 16% of those who die with wills leave something to charity. These figures comport with the percentages reported in federal estate tax returns, indicating that the wealthy may not leave funds to charity in any higher percentage overall than the general population. Thus, it is possible to conservatively estimate the total number of charitable estates to have been in the range of 200,000 in recent years, some 8% of an average of 2,500,000 decedents in recent years, with a large percentage of charitable bequest dollars coming from the larger estates required to file estate tax returns.

In order to understand why the 2001 Tax Act was deemed necessary by Congress, it is helpful to examine the growth of estate tax returns and charitable bequests throughout the 1990s:

The 2001 Tax Act serves to gradually reduce the number of estates subject to estate tax back to the smaller numbers and percentage of the population affected prior to the significant increase in the value of estates during the 1990s. Of course, if the estate tax is completely eliminated in 2010 as planned, we will experience an estate-tax-free environment not seen in America since 1916.

What it all means

What impact will the projected decrease in estate taxes have on charitable giving? While no one can know for sure, some experts are predicting a major decrease in charitable giving through estates. One article predicts that recent tax reforms will lead to a $10 billion annual reduction in charitable gifts.

Others point out that in reality it was not the 2001 Tax Act that had the greatest impact on the estate tax but rather the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981, which served to eliminate the tax for over 95% of the decedent population. Since that time, estate taxes have only applied to, at most, 5% of the population.

One might wonder, then, what happened to charitable bequests after the landmark 1981 legislation. Based upon Giving USA estimates and annual reports on voluntary support of education, charitable bequests have continued to show significant growth over the past twenty years. Additionally, recent pronouncements from researchers concerning the impending intergenerational wealth transfer affirm earlier predictions about the benefits to the nonprofit sector as a result of estate transfers and outright gifts.

Regardless, one thing is certain—charities that overemphasize estate tax benefits of planned giving to the exclusion of other motivations will find the number of donors interested in giving to their institution for that reason alone steadily shrinking. Meanwhile, those who clearly communicate their mission to their constituents and have valid reasons to ask for their support, both today and as part of their long-range financial plans, will continue to thrive.