by Robert F. Sharpe Jr.

Understanding the what, when and how is key.

Some commentators have predicted that this growth may slow down or reverse in light of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (the Act). That is because the Act can be expected to affect nonprofits in ways not previously experienced.

Unlike other widely used deductions, such as mortgage interest and state taxes, the charitable deduction itself emerged from the tax reform process relatively unscathed, although its effective usefulness and value were significantly diminished for many donors.

For example, some are predicting a negative impact from the Act because of the doubling of the standard deduction. The higher standard deduction will significantly reduce the number of individuals who will be able to deduct charitable gifts. As a consequence, many donors will now need to make their gifts from after-tax dollars, and the amount of income required to make a gift will be substantially more than would be required in the case of previously deductible gifts.

Importance of other motivators

History teaches us that even when tax law changes result in an increased after-tax cost of making charitable gifts, giving tends to recover and resume long-term growth trends over time.

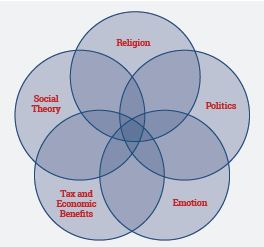

The primary reason for this phenomenon is the influence of a number of powerful non-tax motivators for charitable giving. These can be greater incentives for giving than tax savings as they are rooted in the very fabric of human nature and the society in which we live. They can, in some cases, result in a donor foregoing other personal expenditures for entertainment and other non-essential expenses to make it possible to continue giving at the same levels as when their gifts were deductible.

Let’s examine some important non-tax motivators for charitable gifts of all sizes, whether given during life or through one’s estate.

Religious beliefs

Historically, religion has inspired more charitable gifts than any other motivator. In fact, more charitable gifts are made each year to religious-based charities than any other type of charitable interest. Many of the world’s major religions—including Christianity, Judaism and Islam—incorporate philanthropy as a pillar of their theology.

Historically, religion has inspired more charitable gifts than any other motivator. In fact, more charitable gifts are made each year to religious-based charities than any other type of charitable interest. Many of the world’s major religions—including Christianity, Judaism and Islam—incorporate philanthropy as a pillar of their theology.

Development officers should, as a result, make every effort to understand their donors’ religious beliefs and the influence they may have on the ways individuals choose to make gifts. For example, some religious traditions teach that the greatest spiritual fulfillment when giving is experienced by making gifts anonymously. When this factor is in play, a naming opportunity or other public recognition for a gift may hold little or no attraction for a prospective donor.

Emotional motivations

Virtually every human emotion can inspire a charitable gift. Gifts in memory or in honor of others are emotional decisions and are one of the most powerful motivators for making charitable gifts. Naming opportunities and other means of public recognition can also drive giving behavior for those whose religious beliefs don’t negate that motivator. Gratitude for services rendered by a nonprofit to a donor or a friend or family member is another motivator. Many other donors give because of empathy in response to what they perceive as unnecessary illness or other suffering.

Social theory

People with no religious convictions who pride themselves on acting rationally in all spheres of their lives may still be motivated to make philanthropic gifts. Many individuals hold definite ideas about social responsibility, including the duty to share their wealth with others through voluntary investments in arts, education, the environment and other nonprofit endeavors they see as vital for a healthy society. The term “noblesse oblige” translates as “nobility obligates” and derives from the social concept that those who are privileged carry a burden to act honorably and generously toward other people.

Political beliefs

Closely allied but somewhat different from social motivations are gifts rooted in adherence to a political belief system. Some individuals, for example, are opposed to government taxation and spending for other than a narrow range of activities restricted to courts, military and other purely public needs. They instead believe other societal needs should be met through voluntary contributions. Conversely, there are those who do not give in support of certain needs because they believe it is the responsibility of government to provide for a broader range of societal needs.

Taxes in perspective

The tax and economic benefits related to giving, while important, are perhaps the most misunderstood motivators of charitable gifts. While it’s true there can be significant financial benefits associated with charitable giving, it can be a critical mistake for fundraisers to assume these factors are a primary motivator of gifts in nearly all cases. Careful planning of charitable gifts with attention to the type of property given, the timing and tax consequences can have a major impact on the amount a donor is able to give.

A unique mix

In reality, virtually every gift is made as a result of a unique mix of motivators, and they’re often intertwined. Most larger charitable gifts, whether current or deferred, tend to involve complex relationships among a number of motivating factors. It’s rare to encounter just one.

The most successful fundraisers know they must communicate the nature of their mission and why it is worthy of support. Then after attracting the interest of donors, they then put the “gift” before the “plan.” They know it’s difficult, if not impossible, to transform even the best “what,” “when” and “how” into the “who” and “why” behind a gift.

The most successful fundraisers know they must communicate the nature of their mission and why it is worthy of support. Then after attracting the interest of donors, they then put the “gift” before the “plan.” They know it’s difficult, if not impossible, to transform even the best “what,” “when” and “how” into the “who” and “why” behind a gift.

Robert F. Sharpe Jr. is Chief Consultant for SHARPE newkirk.