by Robert F. Sharpe, Jr.

Editor’s note: The following article is adapted from an article first published by Mr. Sharpe in the June 1987 issue of Give & Take. We hope you will find it just as thought-provoking today.

What do director of development, vice president for development, director of major gifts, director of annual funds, director of planned giving, director of deferred giving, director of special gifts, legacy manager, director of stewardship, director of principal gifts, vice president for advancement, endowment director, executive director of endowment, assistant to the chancellor, president, executive director, stewardship secretary, director of capital giving, associate legal counsel, director of donor relations, director of major and planned gifts, director of resource development, and last but not least, director of fundraising, have in common?

These are all titles of fundraising professionals I have worked with recently. The people who use them are all involved, to a greater or lesser extent, in the process of encouraging individuals to make gifts of cash or other property in support of the organizations and institutions they represent. Some are focusing on current gifts, some on gifts made over time or as a component of a donor’s estate plans, others on gifts for specific purposes such as capital or endowment, and others—all of the above.

Given the understandable confusion arising from this plethora of job labels, we are often asked about titles for nonprofit managers engaged in various aspects of fund development—what titles should and should not be used?

Simply stated

Clearing away the haze, we believe a title should be user-friendly for those with whom one interacts, giving preference to the donor, not just peers within an organization. Imagine you just made a gift of $500 to an organization in response to a request from a friend. Research by the recipient organization has convinced its development staff you are actually capable of making much larger gifts. What would you think if you received an initial thank-you letter and request for a meeting from the “director of major gifts?” In some cases, you might be flattered to be considered important enough to catch the interest of the person in charge of major gifts. In others, you might think this to be a bit presumptuous and even off-putting that you have immediately been “targeted” to make larger gifts.

Ironically, in a smaller shop with limited staff and led by a “director of development” who typically wears many hats, there may be an advantage in using a title like this that broadly suggests one’s area of responsibility, but doesn’t “pigeonhole” the donor into a slot on the organizational chart of a large bureaucracy. This leaves the director of development the freedom to move between current and deferred gifts, as well as the ability to discuss various uses for the gift such as capital, endowment, or operations.

The real challenge comes in larger programs where specialization has, of necessity, developed over time. How do we assign titles that help maintain institutional order while meeting the needs of donors and making sure that the staff has the flexibility it needs when working with donors?

This is especially true when considering the area of major and planned gifts—one where there can increasingly be an overlap of functions—particularly when working with older, wealthier donors. Many now use the titles “director of planned giving,” or “director of gift planning.” These can be very useful titles where an organization has the volume of activity necessary to employ one or more specialists in this area.

In 1988, we first proposed the definition of “planned giving” that follows:

“A planned gift is any gift of any kind for any amount given for any purpose—operations, capital expansion, or endowment—whether given currently or deferred if the assistance of a professional staff person, qualified volunteer, or the donor’s advisors is necessary to complete the gift. In addition, it includes any gift which is carefully considered by a donor in light of estate and financial plans.” —Give & Take, March 1988

While it is often desirable to employ specialists in planned giving, it is increasingly the case that people who use other titles may also sometimes be engaging in gift planning to a greater or lesser extent. The proliferation of information about planned giving on institutional Web sites and as part of other development activities will add impetus to this trend. Those who specialize in planned giving may likewise find themselves involved in other aspects of fundraising from time to time.

Clarity is the key

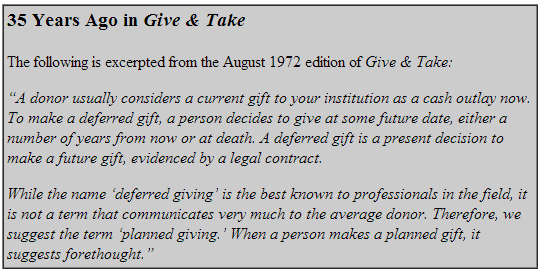

There is no right or wrong answer to the “title question.” First and foremost, however, it is important that titles be considered from the perspective of the message being conveyed to a prospective donor, and should be flexible enough to allow a staff member the ability to best serve a donor. This was in fact the impetus for originally moving from the term “deferred giving” to the broader term “planned giving” in the early 1970s. (See box below.)

We often hear complaints about how an organization has developed “silos” that can stifle effective cooperation among staff and inhibit the ability to serve donors. In our experience, these situations are not intentional, but sometimes stem from the use of language in designing titles and organizational charts.

The key is to make an organization as complex and specialized as is needed to best serve donors and make sure everyone knows their position on “the team.” But remember, from the donor’s perspective, he or she is more interested in watching how the team plays the game than the nuances of the manager’s playbook or the roster of positions.