In recent years, studies published in the U.S. and elsewhere have revealed trends in the profiles of those who intend to include charitable contributions as part of their estate plans. A national survey sponsored by the National Committee on Planned Giving in 2000 revealed, among other things, that 8% of the population claims to have included charitable bequest provisions in their estate plans. This represents a 60% increase over the results of the NCPG’s earlier study in 1992. Other surveys have indicated that upwards of 50% of affluent Americans intend to include charitable provisions in their estate plans.

These and other surveys contain helpful information about the charitable intentions of Americans as they relate to their estate plans. However, as intentions do not always become reality, it can also be useful to examine the fulfilled actions of a portion of America’s decedent population over a period of years.

One source of such information is the Internal Revenue Service. The most comprehensive published figures available are included periodically in the IRS’s Statistics of Income Bulletin. Recent reports feature in-depth analyses of the estate tax returns of individuals who died between 1995 and 2000. The data, projections, and estimates from the Internal Revenue Service can provide a wealth of information about planned giving donors and prospects (see www.irs.gov).

Crunching the numbers

Among those who filed estate tax returns in 1998, the average female decedent passed away at 81.4 years, almost five years later than the male decedent’s 76.6 years. Both lived slightly longer than the general population. Those who had entered into planned gifts lived even longer.

The composition of estates reveals that stocks and bonds made up the bulk of the assets in the estates of both male and female decedents. Cash amounted to only about 11% of combined assets.

The marital deduction and charitable deduction are the two most popular estate tax deductions. For 1998, the charitable deduction was claimed in 16.9% of the federal estate tax returns filed, which falls within the normal 15-20% observed in other years. As 80% or more of wealthy persons do not yet make gifts that result in charitable deductions from estate taxes, there may be tremendous opportunities for growth in gifts via estates. Meanwhile, NCPG figures indicate that there has been a dramatic increase in planned giving donors among the general population of ordinary Americans.

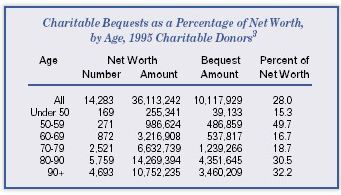

Gross contributions claimed on estate tax returns exceeded $13.6 billion in 1998. The IRS study reveals that charitable bequests in estates on average amounted to 28.7% of the estate net worth.

Factors affecting charitable gifts

Gender. Without a doubt, gender plays a role in giving patterns. Women are significantly more likely to include charitable provisions in their estates than are men. Overall, 13.4% of male decedents left $7.2 billion and 21.0% of female decedents left charitable bequests of $7.7 billion. This difference may be explained by the fact that women tend to live longer than men, and as a result wives often outlive their husbands. The first spouse to die in a married couple would likely take advantage of the unlimited marital deduction by leaving all assets to the surviving spouse. In these cases, the second spouse to die, in most cases women, would naturally attend to the ultimate charitable disposition of the couple’s accumulated assets.

While women were more likely to leave bequest gifts, note that men actually contributed more per capita.

Marital status. Single (defined as never married) females and males were the most likely to include charitable bequests in their wills. Almost half of all single females studied, and roughly one-third of all single males, included charitable provisions in their estate plans, compared with roughly 25% of widowed men and women and fewer than 10% of married decedents. Single decedents also contributed a larger percentage of their net worth than married or widowed contributors. In total numbers, widows and widowers tend to constitute the largest source of charitable bequests. Again, the impact of the unlimited marital deduction and the need for a surviving spouse to have access to the entire marital estate for the remainder of life would largely explain the fact that married decedents were far less likely than their widowed and single counterparts to include a charitable bequest in their plans.

Age. In 1995, those persons over the age of 80 at the time of death represented almost three-quarters of all charitable contributors from estates. Over 90% of bequest money came from those who died after the age of 70. Interestingly, while the largest percentage of net worth was given by decedents who were between the ages of 50 and 60 at the time of death, only 440 estate tax returns for persons under 60 contained charitable provisions. Again, this reflects the fact that most younger decedents fall into the category of married men, who are the least likely to leave a bequest to charity through their will or other plans.

Looking ahead

Published IRS data should provide encouragement for all persons involved in the gift planning process. They provide solid evidence that the growing transfer of wealth is becoming a source of increased charitable giving and can be expected to grow in the future.

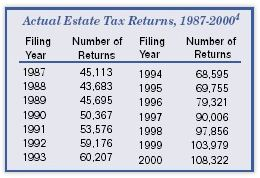

Evidence of the increasing size of estates is shown by the rise in the number of federal estate tax returns filed between 1987 and 2000 (see chart below).

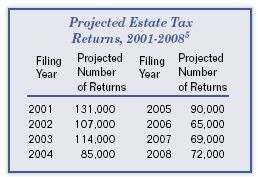

As part of the 2001 Tax Act, the filing level increases to $1 million in 2002, $1.5 million in 2004, $2 million in 2006, $3.5 million in 2009, the tax is repealed in 2010, and, unless Congress acts to make the estate tax cuts permanent, is scheduled to return to $1 million in 2011. While the actual impact of the estate tax cuts remains to be seen, one could reasonably assume that many, if not most, of those persons that fit the charitable bequest profile (older, single, childless, widowed, etc.) will continue to include charities in their estate plans. Such was the case after the 1981 tax act eventually eliminated estate taxes for most decedents through the introduction of the unlimited marital deduction and the original $600,000 exemption equivalent. See below for the IRS’s projected estate tax returns for 2001-2008.

Marketing efforts pay off

While surveys have indicated that up to 50% of affluent persons intend to include charities in their estates, the NCPG study shows that only 8% of Americans overall have actually included charitable dispositions in their estates. As noted earlier, IRS statistics indicate that less than 20% of the affluent actually take this step. It therefore appears that there is considerable room and promise for donor education and motivational activities on the topic of charitable bequests and other testamentary gifts to help bring stated intentions in line with reality.

Given these statistics, one might reasonably assume that an organization could enjoy significant growth in this source of gift income simply by encouraging those who have charitable intentions to follow through! One effective way to turn prospective donors into committed supporters is to send them appropriate and timely marketing materials (see page 3). The 2000 NCPG study supports this idea as it indicates that the number one way donors learn about making charitable bequests is through charities’ marketing efforts.

Ongoing and effective communications with your constituency may well be the key to helping your donors turn their charitable intentions into a reality. It is both the duty and privilege of gift planners to help donors leave a lasting legacy for the future.