President Reagan signed the Tax Reform Act of 1986 with members of Congress and White House staff present on the south lawn (seen at left). Is another major change on the horizon, and how will it impact giving?

More than 30 years have passed since the Tax Reform Act of 1986, and nearly 50 years since the Tax Reform Act of 1969.

Both of these landmark bills included legislation that significantly impacted charitable giving, and once again the prospect for comprehensive tax reform appears to be a real possibility.

Both the executive and legislative branches of government have announced plans to address tax reform in 2017, and fundraisers need to stay up to date on any proposed changes. While taxes are rarely the primary motivation for making a charitable gift, they often affect the size, form and timing of gifts.

Learning from history

The conversation about taxes and giving is not new; in fact, it goes back to ancient times. For example, in the Bible, the book of Genesis states that Pharaoh should receive a fifth of all produce of the land as a tax, except for the land of the priests (Genesis 47:26). In other words, this 20 percent flat tax carved out a charitable exemption for religion.

In the early part of the 20th century, Congress developed the modern U.S. tax system. In 1917, Congress enacted the charitable deduction to exempt funds given to qualified charitable organizations from being taxed prior to their donation, up to certain limits. (See Page 3 for more details.) Even though the rules and regulations have been adjusted, that basic system is still in place today.

Modern times

The Tax Reform Act of 1969 included specific reform measures targeted at real and perceived abuses in the charitable tax planning arena. Instead of simply eliminating the charitable deduction to remedy these issues, lawmakers took the time and effort needed to adjust the rules and regulations to stem potential abuses, protect the fundamental functions of charitable foundations and preserve certain split interest gift techniques.

As a result, both charitable foundation formation and split interest gifts, like charitable remainder trusts, grew substantially in numbers in the decades after the 1969 tax reform. Other forms of giving also flourished over time. According to Giving USA, total charitable giving amounted to approximately $20.66 billion in 1969, $83.79 billion in 1986 and $373.25 billion in 2015.

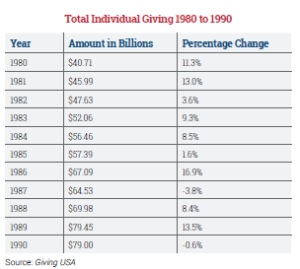

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 attempted to simplify the tax code by reducing or eliminating tax brackets, in addition to curtailing certain deductions, credits and other tax-advantaged activity. The charitable deduction and home mortgage deduction were left unscathed. However, the Tax Reform Act of 1986 provides a vivid example of how tax law changes can affect charitable giving. With the top marginal income tax bracket reduced from 50 percent to 28 percent, many individuals accelerated gifts in 1986 in order to take advantage of greater tax savings that year. The following year (1987, the year the act went into effect) saw the first decline in individual giving since Giving USA began its reports in 1955.

Current proposals

The main tax reform proposals circulating today are again designed to simplify the U.S. tax code, lower rates and encourage economic growth. The House/G.O.P. Blueprint and White House/Trump proposals have more similarities than differences, and neither proposal directly targets charitable gifts. Nonetheless, lower tax rates, fewer taxpayers itemizing deductions, a possible cap on all deductions and a proposed two percent floor on charitable gifts could result in an increase in the after-tax cost of giving in the future for many.

The bottom line?

Looking back over more than 50 years of serving America’s nonprofit community, Sharpe Group’s experience reveals that some donors will continue to give to charity in spite of limits on tax benefits. People have continued to claim deductions even if the savings were reduced as a result of lower rates or other adjustments like the Pease Amendment. Donors decide to make charitable gifts out of discretionary income and assets, and if tax law changes tend to grow those available assets, that increase may be as important or more important than the tax incentive itself.

On the other hand, if donors’ income does not rise and they must first pay tax on income before making a donation, the after-tax income from which to make gifts is reduced and could shrink the amount they believe they can give.

Even if the charitable deduction were eliminated, many people would continue to give the same amount where their interests are greatest, while perhaps giving less overall. People gave generously before there was a federal income tax deduction to encourage gifts, and they will continue to give after tax reforms to the extent their after-tax income permits.

Now is the time to make sure your donors understand why your missions are vital (see “Are You Near, Dear and Clear?”) and why they should continue their support even if the after-tax cost of doing so increases. ■