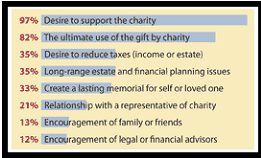

The desire to create a lasting memorial for oneself or a loved one motivates almost as many charitable bequest donors as tax and financial considerations. That was one finding of a survey conducted in 2000 by the National Committee on Planned Giving (NCPG), now the Partnership for Philanthropic Planning (PPP). The wish to memorialize a loved one was listed as a motivation for bequests by 33 percent of respondents (see chart at right).

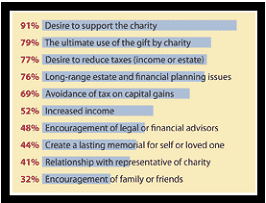

The same report revealed an even greater role for memorial gift motivations by those who had established charitable remainder trusts (see chart at left).

The same report revealed an even greater role for memorial gift motivations by those who had established charitable remainder trusts (see chart at left).

Numerous colleges, universities, museums and other organizations can offer noteworthy examples of memorial gifts.

Harvard University was named in honor of its first benefactor, John Harvard, who donated his personal library and half of his estate in a bequest to the emerging university.

Leland and Jane Stanford established Stanford University for “California’s children” in memory of their only child, who died at the age of 16.

Memorial considerations often play a major role in the decision to give. Fundraisers should pay attention to this potential to increase funding from bequests and other planned gifts while also generating an additional source of current gift income.

Yet programs designed to encourage gifts in memory of or in tribute to others are often overlooked or underutilized.

Current gifts can lead to more

Memorial gift programs often revolve largely around the process of receiving, receipting and acknowledging memorial gifts sent “in lieu of flowers” at the time of someone’s death. These gifts typically come as a result of a donor’s decision to honor a family’s wishes and may or may not be an indication of any donative intent on the part of the donor.

Although a program like this can produce a significant stream of small current gifts, it represents only a portion of the funding that can be derived from efforts to serve a donor constituency through a more comprehensive memorial and tribute gift program.

In addition to welcoming gifts made in memory of a decedent soon after death, consider including a line on your response devices sent with gift solicitations that allows a donor to make a gift in memory or honor of a loved one.

Experience shows that those who make gifts in memory of the same person on more than one occasion are much more likely to leave a bequest to the same organization, whether or not the bequest is specifically designated in the will as a memorial gift. Studies of wills that contain gifts for charitable purposes have revealed that bequests from the estates of persons who had made one or more gifts to an organization in memory of a loved one during their lifetime tend to be two to three times larger than bequests left by others.

How to strengthen your memorial gifts program

To fully realize the potential for memorial gifts to your organization or institution, consider these suggestions:

1. Be sure your existing process for encouraging, receiving, receipting and acknowledging memorial gifts is running smoothly. It is especially important that memorial gifts of any size be handled quickly and acknowledged to donors and the survivors of those who have been commemorated.

2. At some point after you have acknowledged every gift in memory of a friend or loved one, consider presenting a list of donors’ names in a framed certificate or perhaps a scroll that can be delivered to the closest surviving loved ones. This will remind them of the importance of your organization in the life of the deceased and could well lead to the decision to make additional gifts during lifetime and as part of a surviving loved one’s estate.

3. Once you know that all memorial gift donors have been properly acknowledged, make certain donors receive future information on charitable gift planning as you communicate with others who may have been selected to receive this information on account of age, longevity of giving or other factors.

4. Consider adding an honorary or tribute component to development programs designed to encourage outright gifts, bequests and other planned gifts. Try including a special insert with regular acknowledgment letters or follow up with special communications focused on memorial and tribute gifts.

5. Make sure you have a readily available list of commemorative naming opportunities, including named funds, buildings, rooms and programs, with appropriate minimum donations and funding options.

6. If appropriate, consider sending on a periodic basis information encouraging memorial gifts to all prior donors regardless of whether they have made memorial gifts in the past. This communication may be structured around anniversaries, birthdays, times of religious significance, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day or Memorial Day.

7. Examine major and planned gift proposals and consider adding a memorial element. Pay special attention to choosing the proper person to be recognized, whether it’s the donor, another family member or a close friend or mentor. A suitable and tastefully presented opportunity to honor a loved one in a special way may make the difference in a donor’s decision to fund a gift.

8. Always remember to think about the gift from the donor’s perspective. In some cases it may be appropriate to recognize donors who did not seek recognition for themselves. Be sure, however, always to obtain the donor’s approval before bestowing this recognition. Examples of recognition include gift clubs, societies, walls of honor or other appropriate programs. Remember that a listing in a permanent bequest recognition society is tantamount to creating a lasting memorial in memory of that donor, something some may desire though they would never initiate a request for this recognition on their own.

It is important to consider all possible motivations for the completion of larger gifts. The desire to give in honor or memory of others is among the most powerful and timeless of motivators—and facilitating such gifts can be a welcome way to provide additional service to your constituency.