The May issue of Give & Take addressed the question of when Baby Boomers can be expected to more fully embrace philanthropy and whether they can replace the extraordinary generosity of the Greatest Generation. The answer to this question has huge implications, as approximately 70 million persons will reach the age of 65 over the next 20 years.

The first article in this series examined how some Boomers may be able to tap into retirement plan assets to make larger gifts now and in the future. For one segment of Boomer donors the idea of using these assets as a source of “tax-free giving” will be very attractive. For others, different gift planning strategies may hold more appeal. For example, many Boomers hold substantial assets outside of their retirement funds at the time they may be considering retiring or scaling back on their work-load. Their personal objectives, therefore, are quite different from those of the potential donors studied in Part I of this series.

A bridge to retirement

These Boomers may be able to use charitable remainder trusts in creative ways to make a “bridge to retirement” that allows them to simultaneously achieve personal and philanthropic goals.

Charitable remainder trusts, which can last for a period of up to 20 years, will no doubt prove useful to a broad range of Boomers who want to make significant gifts while enjoying a temporary source of income, significant income tax deductions, portfolio diversifications, and other benefits, such as profession-al money management.

In the year 2005 a Boomer born in 1955 will turn 50 years old every eight seconds. As it will in most cases be nearly a decade before they are allowed to withdraw funds from tax-favored retirement accounts without penalty at age 59 1/2, charitable remainder trusts for 10-year periods may be an ideal solution to unlock the additional income needed during the 10-year wait.

A case in point

Consider George. At 55 years, he has a net worth of over $10 million, much of which is in the form of his closely held business. He plans to retire at age 65, sell the business for a significant sum, and begin taking large withdrawals from his retirement plans. He also expects to receive a significant inheritance from his 87-year-old mother.

In the meantime, George has been asked to make a $1 million gift to support an endowment campaign for his primary charitable interest. While he would like to make the gift, he doesn’t think he can, given obligations to pay for his children’s education, weddings, and other financial priorities.

Among other investments, George owns securities worth $2 million that pay no dividends. Five years ago, the securities were worth $2.5 million. His cost basis is $400,000. He has thought about selling the securities but doesn’t want to pay what amounts to $240,000 in capital gains tax.

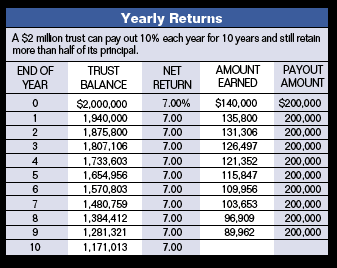

In consultation with his advisors and representatives of the charity, George decides to use the securities to fund a 10% charitable remainder annuity trust that will make annual fixed payments to him of $200,000 each year for 10 years.

He will be allowed a charitable income tax deduction of just over $440,000, resulting in a tax savings in his bracket of more than $150,000. The tax savings may be spread over several years be-cause of the size of the gift. Because most of the payments he receives from the annuity trust will be characterized as capital gain, dividends, or a return of principal, the effective tax rate on the payments will be relatively low. In the first year, his after-tax payment will be about $165,000.

If the investments in the trust earn a net return of 7% each year, at the termination of the trust the charity will receive about $1.17 million (see chart above). Under gift valuation guidelines released in April 2004 by the National Committee on Planned Giving, a charity would value George’s gift at just under $1 million after adjusting the expected remainder for anticipated inflation of 3.4% during the term of the trust. (For more on the NCPG Valuation Standards, see www.ncpg.org.)

George has made an extremely meaningful gift, while enjoying pre-tax payments equaling the amount originally placed in the trust. The cash flow from the trust can be used to pay for life insurance, education, weddings, or any other expenses that may arise. Note that only the assets in the trust are at risk and the charity is not obligated to make the payments, although George can be reasonably certain to receive his payments. This can be especially helpful when planning for fixed expenses such as insurance premiums.

If the trust earns just 4% each year, there will still be over $500,000 remaining in the trust at termination. One might consider this gift to be tantamount to a charitable gift annuity for a term of years, something that is not possible using the traditional gift annuity structure.

The potential market for the plan outlined above is not bounded by age constraints. It works as well for a 40-year-old as it does for a 60-year-old. It applies to people of any age who own assets they would like to give in a tax-efficient way but would also like to reserve income for a period of time.

Charities and gift planners that embrace the Baby Boom generation, understand it, and adapt planning strategies to meet their needs as they grow older can expect to participate in the unfolding transfer of wealth, both now and in the future. Because of the sheer size of this generation, it will be especially important to use age, wealth, and stage of life analysis to identify gift strategies that will be effective with Boomers. Look for future articles on this topic to learn additional strategies on dealing with Boomers as they enter the prime giving years.

Editor’s note: This article is excerpted from materials presented in the popular Sharpe seminar “Major Gift Planning.” Now in its sixteenth year, the next presentation will be in New York City on September 8 and 9. See page 3 or www.sharpenet.com/seminars/ for more information.